Updated RIA for Supporting Statement

Uniform Act Final Rule RIA_dvid28592 - P20 comments af working 10-19-2023 HEPR responses.docx

State Right-of-Way Operations Manuals

Updated RIA for Supporting Statement

OMB: 2125-0586

Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition for Federal and Federally Assisted Programs

Final Rule Regulatory Impact Analysis

Docket FHWA-2018-0039

July 19, 2023

Prepared for:

Federal Highway Administration

Office of Real Estate Services

Washington, DC

Notice

This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof.

The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report.

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE |

Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 |

|||||

Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. |

||||||

1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank)

|

2. REPORT DATE July 19, 2023 |

3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED

|

||||

4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition for Federal and federally assisted Programs: Final Rule Regulatory Impact Analysis |

5a. FUNDING NUMBERS 693JJ319N300029 |

|||||

6. AUTHOR(S) Catherine Taylor; Sarah Plotnick; Faisal Ajam; Emily Futcher; Carson Poe; Melissa Corder; Arnold Feldman |

5b. CONTRACT NUMBER N/A |

|||||

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) U.S. Department of Transportation Volpe National Transportation Systems Center 55 Broadway, Kendall Square Cambridge, MA 02142 |

8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER

|

|||||

9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration Office of Real Estate Services 1200 New Jersey Ave, SE Washington, DC 20590 |

10.

SPONSORING/MONITORING

|

|||||

11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

|

||||||

12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

|

12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE

|

|||||

13. ABSTRACT (Maximum 200 words) This regulatory impact analysis estimates the costs and benefits associated with the final rule for the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970. |

||||||

14. SUBJECT TERMS

|

15. NUMBER OF PAGES 79 |

|||||

16. PRICE CODE

|

||||||

17.

SECURITY CLASSIFICATION

|

18.

SECURITY CLASSIFICATION

|

19.

SECURITY CLASSIFICATION

|

20. LIMITATION OF ABSTRACT

|

|||

|

|

|

Standard Form 298 (Rev. 2-89) Prescribed by ANSI Std. 239-18 |

|||

Contents

1.1 Summary of Proposed and Final Rule 12

1.3 Program Responsibilities and Expenditure Areas 14

1.4 Need for Regulatory Action 14

1.4.2 Interagency Coordination 16

1.4.3 Practitioner Input and Research 17

1.5 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking 18

1.7 Assumptions and Methodology for Cost-Benefit Analysis 21

2. Residential Displacements 22

2.3.1 Administrative Cost Savings 24

2.3.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 27

2.4 Homeowner 90 Day Eligibility 27

2.4.1 Administrative Cost Savings 27

2.4.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 29

2.5.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 31

2.6 Rental Application and Credit Check Fees 32

2.6.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 33

2.7.1 Administrative Cost Savings 34

2.7.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 35

3. Non-residential Displacements 36

3.3 Reimbursement for Updating Other Media 38

3.3.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 39

3.4.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 40

3.5 Re-establishment expenses 43

3.5.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 44

3.6 Fixed Payment In-Lieu-of Moving Expenses 47

3.6.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 48

3.7.1 Administrative Cost Savings 51

3.7.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 51

4.1 Appraisal Waiver Valuations 52

4.1.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 52

4.2 First and Second Tier Waiver Valuations 52

4.2.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 53

4.3 Third Tier of Waiver Valuations 53

4.3.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 53

4.4.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 54

4.5 Inspection of Comparable Replacement Dwellings 54

4.5.2 Transfer (Increased Program Expenditures) 55

4.6 Other Clarifications and Streamlining 55

4.7 Legal Status Verification 57

4.7.2 Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) 58

4.8 Revising Program Materials 58

4.9 Federal Agency Reporting Requirement 59

List of Figures

Figure 1. Residential Relocations (FHWA) 23

Figure 2. Last Resort Housing as a Percent of All Residential Displacements (FHWA) 25

List of Tables

Table 1. Federal Agencies Potentially Subject to the Uniform Act 20

Table 2. Benefits from Increasing Maximum Amounts for Replacement Housing Assistance (FHWA) 27

Table 5. Administrative Costs of Reverse Mortgages (All Agencies) 32

Table 7. Non-Residential Maximum Payments 37

Table 8. Change in Search Expense Reimbursement for Non-residential Relocations (FHWA) 43

Table 9. Change in Re-establishment Expense for Non-residential Relocations (FHWA) 47

Table 10. Change in Fixed Payments In-Lieu-of Moving Costs for Non-residential Relocations (FHWA) 51

Table 11. Costs to Update Program Materials (All Agencies) 59

Abbreviations and Acronyms

BRARS |

Business Relocation Assistance Retrospective Study |

CFR |

Code of Federal Regulations |

DOD |

U.S. Department of Defense |

DOE |

U.S. Department of Energy |

DOI |

U.S. Department of the Interior |

DOJ |

U.S. Department of Justice |

DOT |

U.S. Department of Transportation |

DSS |

Decent, Safe, and Sanitary |

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

FRA |

Federal Railroad Administration |

FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

GAO |

U.S. Government Accountability Office |

GSA |

General Services Administration |

HHS |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

HUD |

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

MAP-21 |

Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century |

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

RHP |

Replacement Housing Payment—Owners |

RRHP |

Rental Replacement Housing Payment—Tenants |

RUS |

Rural Utilities Service |

TVA |

Tennessee Valley Authority |

Uniform Act |

Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 |

USACE |

U.S. Army Corp of Engineers |

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

VA |

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs |

Executive Summary

The Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 (Uniform Act) provides important protections and assistance for people affected by federally funded projects. Congress passed the law to safeguard people whose real property is acquired or who move from their homes, businesses, nonprofit organizations, or farms as a result of projects receiving Federal funds. The Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) modified the statutory payment levels for which displaced persons may be eligible under the Uniform Act’s implementing regulations, necessitating the current rule. In addition, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is making changes to wording and section organization to better reflect the Federal experience implementing Uniform Act programs since the last comprehensive rulemaking for 49 CFR 24, which occurred in 2005. At the Federal level, 14 departments and 5 independent Agencies are subject to the Uniform Act, and their input was reflected in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM). Subsequent to the NPRM, FHWA responded to additional input from those Federal Agencies, recipients, and other members of the public. The final rule reflects that input.

This regulatory evaluation is largely similar to the regulatory evaluation of the NPRM. However, it has been revised to reflect changes in the final rule compared to the NPRM and to update the analysis given that roughly 3 years have passed since the analysis conducted for the NPRM. No public comments were received related to the Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) for the NPRM.

The costs of the final rule over 10 years for all Uniform Act Agencies are estimated to be $2.2 million when discounted at 7 percent and $2.4 million when discounted at 3 percent. The annualized costs are estimated to be $311,000 per year when discounted at 7 percent and $283,000 per year when discounted at 3 percent. The larger impact of this final rule is in the form of transfers from the displacing Agencies to property owners whose real estate is acquired for Federal projects. Transfers over the 10-year analysis period resulting from this rule are estimated to be $169.5 million when discounted at 7 percent and $214.6 million when discounted at 3 percent or roughly $24.1 million per year when annualized at 7 percent or $25.2 million per year when annualized at 3 percent. This rule can therefore be thought of as predominantly a transfer rule, as the estimated social costs are significantly smaller than those transfers from the displacing Agencies to those compensated. The FHWA was the only Agency that provided data upon which to base estimates of the transfers. Therefore, the magnitude of the change in transfers for all Federal Agencies may be somewhat larger than is reported here.

The bulk of the estimated costs are related to updating program materials to reflect the changes in the final rule. In addition, some smaller recipient and Federal Agency administrative cost savings have been estimated.1 Again, FHWA was the only Agency that had a detailed data set available for its Uniform Act Program, and therefore only the administrative cost savings to FHWA have been estimated here. Based on communications with other Uniform Act Agencies, FHWA analysts believe that FHWA has the largest Uniform Act Program; however, other Agencies have sizable programs as well. Therefore, the total cost savings across all Agencies will likely be larger.

The benefits of the final rule primarily relate to improved equity and fairness to entities that are displaced from their properties or that move as a result of projects receiving Federal funds. For example, the final rule raises the statutory maximums for payments to displaced entities to assist with the re-establishment of the business, farm, or nonprofit organization. There is strong evidence that entities experience re-establishment costs well above the current maximum amount. Raising the maximum payment levels would compensate those entities more fairly and equitably for the negative impacts they experience as a result of a Federal or federally assisted project. However, the fairness and equity benefits of the final rule cannot be quantified or monetized. The higher level of payments may also contribute to more entities being able to successfully re-establish after displacement.

The final rule contains changes, such as a requirement for annual reporting, that can be expected to improve transparency, and, therefore, oversight of the program. Again, that benefit is not quantified or monetized.

The table below offers a summary of the costs and benefits of the final rule over the 10-year analysis period. Given that the benefits of the rule related to equity and fairness have not been quantified, it would be misleading to report a calculation of net benefits for this final rule. Nonetheless, the benefits related to equity and fairness are believed to be sufficient to justify the cost of the final rule.

Summary of Costs and Benefits for Analysis Period 2023-2032

Item |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

Annualized 7% |

Annualized 3% |

Costs |

|

|

|

|

Reverse Mortgages |

$29,046 |

$36,647 |

$4,136 |

$4,296 |

Revising Program Materials |

$2,216,271 |

$2,451,123 |

$315,547 |

$287,346 |

Federal Agency Reporting Requirement |

$184,582 |

$232,883 |

$26,280 |

$27,301 |

Cost Savings |

|

|

|

|

Revising Max. RHP/RRHP (FHWA Only) |

($235,772) |

($300,627) |

($33,569) |

($35,243) |

Homeowner 90 Day Eligibility (FHWA Only) |

($7,286) |

($9,193) |

($1,037) |

($1,078) |

Appraisal Waivers |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Third Tier of Waiver Valuations |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Use of Single Agents |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Inspection of Comparable Housing |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Other Clarity & Streamlining Changes |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Total Costs* |

$2,186,841 |

$2,410,833 |

$311,357 |

$282,623 |

Benefits |

|

|

|

|

Equity & Fairness |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Program Oversight |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding |

||||

Transfers to Displaced Persons for Analysis Period 2023—2032 (FHWA)

Item |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

Annualized 7% |

Annualized 3% |

Residential |

|

|

|

|

Revising Max. RHP/RRHP |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

Homeowner 90-day Eligibility2 |

$1,770,513 |

$2,231,474 |

$252,081 |

$261,597 |

Reverse Mortgages |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Rental Application and Credit Check Fees |

$2,239,669 |

$2,825,733 |

$318,879 |

$331,262 |

Nonresidential displaced persons |

|

|

|

|

Reimbursement for Updating Other Media |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Not Quantified |

Search Expenses3 |

$8,072,686 |

$10,257,668 |

$1,149,369 |

$1,202,512 |

Re-Establishment Expenses |

$125,461,485 |

$158,817,606 |

$17,862,893 |

$18,618,268 |

Fixed Payments In-Lieu-Of Moving Expenses |

$31,997,535 |

$40,514,920 |

$4,555,729 |

$4,749,585 |

Total* |

$169,541,889 |

$214,647,402 |

$24,138,951 |

$25,163,224 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding |

|

|

|

|

The Uniform Act provides important protections and assistance for people affected by federally funded projects. Congress passed the law to safeguard people whose real property is acquired or who move from their homes, businesses, nonprofit organizations, or farms as a result of projects receiving Federal funds. The Uniform Act ensures that these persons are treated fairly and equitably and receive just compensation for and assistance in moving from their properties.

The changes in this rule are necessitated in part by the MAP-21. The MAP-21 increased the maximum statutory payment levels for which certain displaced persons may be eligible under the Uniform Act’s implementing regulations at Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 24 (49 CFR part 24). Specifically, it:

amended the statutory maximum for replacement housing payments for displaced homeowners and displaced tenants;

amended the maximum statutory payment amount for non-residential re-establishment expenses;

amended the maximum fixed payment amount for non-residential displacements; and

reduced the length of occupancy requirement for displaced homeowners to be eligible for replacement housing payments from 180 days to 90 days.4

The FHWA used the rulemaking opportunity provided by MAP-21 to review input on Uniform Act implementation issues that it has collected over recent years. Accordingly, in the NPRM FHWA proposed to make changes to wording and section organization to better reflect the Federal experience implementing Uniform Act Programs, since the last comprehensive rulemaking for 49 CFR 24 in 2005. The NPRM contained the MAP-21 changes and the following proposed changes:

addressed how Agencies should handle reverse mortgages also called home equity conversion mortgages (HECM);

provided reimbursement for updating other media for non-residential displacements;

increased the maximum amount of reimbursement for non-residential search expenses;

provided administrative streamlining changes related to:

facilitating use of appraisal waivers,

introduction of a third tier of waiver valuations,

expansion of the use of the single agent concept,

increased flexibility for inspection of comparable housing, and

other clarifications and streamlining efforts;

addressed how to conduct legal status verification;

how to adjust certain monetary limits and benefits payments for inflation and other factors;

introduced new Federal Agency reporting requirements.

In general, the proposed changes from the NPRM are included in the final rule. However, in response to comments received to the NPRM, the final rule makes the following adjustments to the NPRM:

allows costs related rental applications and credit checks to be reimbursed;

includes new flexibilities related to how an Agency can pay displaced persons for self-moves;

provides an option for Agencies to develop an estimate of move costs, i.e. a “move cost finding”, of up to $5,000 for uncomplicated non-residential moves;

increases the threshold for tier 1 and tier 2 waiver valuations;

modifies the requirements regarding the implementation of the tier 3 waiver valuation;

allows the thresholds for appraisal waivers and tiers of waiver valuations and for conflict of interest, 49 CFR 24.102(n), to be adjusted in the future;

allows the maximum amount of reimbursement for non-residential search expenses to be adjusted in the future; and

provides additional clarifications and streamlining measures related to section 24.101 Voluntary Acquisitions.

When the Uniform Act was enacted January 1971, Federal Agencies that administered programs requiring real property acquisition individually implemented their own regulations. In March 1978, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a Report to Congress beginning a movement within the government that led to the 1985 publication of a model “Common Rule,” with the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) serving as the Lead Agency. At that time, all affected Federal Agencies issued their own rules based on the model. In 1987, Congress passed The Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act of 1987, amending the Uniform Act and confirming DOT as Lead Agency, which U.S. DOT delegated to FHWA. Two years later, FHWA issued a Final Unified Rule, and the other Federal Agencies rescinded their own rules and provided cross references in their policies to the governmentwide regulation at 49 CFR 24 that has since implemented the Uniform Act.

FHWA’s primary responsibilities as Lead Agency are to:

Develop, publish, issue, and update the regulations necessary to carry out the Uniform Act.

Provide Uniform Act leadership, advisory assistance, and training materials for all affected Federal Agencies.

Monitor implementation and enforcement of the Uniform Act in coordination with other Federal Agencies.

Acting as Lead Agency, FHWA is now proposing to amend 49 CFR 24. This activity would affect the land acquisition and displacement activities of all Federal Agencies subject to the Uniform Act (See Section 1.5).5

The Uniform Act provides for compensation to owners whose property is acquired for Federal or federally assisted projects to ensure their fair and consistent treatment, as well as to persons displaced as a direct result of Federal or federally assisted projects, so that they will not suffer disproportionate adverse effects as a result of projects designed for the benefit of the public as a whole. Agencies conducting a program or project under the Uniform Act must carry out their legal responsibilities to affected property owners and displaced persons. These responsibilities include:

For Real Property Acquisition

Appraise the property to be acquired before negotiations.

Invite the property owner to accompany the appraiser during the property inspection.

Provide the owner with a written offer of just compensation and summary of what is being acquired.

Pay for the property before taking possession.

Reimburse expenses resulting from the transfer of title such as recording fees, prepaid real estate taxes, or other expenses.

For Residential Displacements

Provide relocation assistance advisory services to displaced tenants and owner occupants.

Provide a minimum of 90-days advance written notice of the earliest date an occupant may be required to vacate a property being acquired.

Reimbursement of moving and related expenses.

Identify comparable replacement housing that is decent, safe, and sanitary (DSS), and provide payment for the added cost of renting or purchasing the comparable replacement housing.

For Non-residential Displacements

Provide relocation assistance advisory services.

Provide a minimum of 90-days advance written notice of the earliest date an occupant may be required to vacate a property being acquired.

Reimburse for moving, re-establishment, and related expenses as applicable.

Since publication of the last Uniform Act Final Rule in 2005, FHWA has undertaken a comprehensive effort to identify potential opportunities for improving Uniform Act implementation. The FHWA initiatives have included research on the need for regulatory and statutory change to the Uniform Act; co-sponsorship of national symposiums on Uniform Act implementation issues; implementation of pilot projects designed to determine the effect of changes in certain Uniform Act requirements and procedures and an examination of the experiences of several State departments of transportation (State DOTs) in providing payments required by State law which supplemented Uniform Act benefits. These activities confirmed that there are a number of improvements to implementation that could be made which would clarify existing requirements, reduce administrative burdens recipients and Federal Agencies, and improve the government’s service to individuals and businesses affected by Federal or federally assisted projects and programs. The mandated changes in MAP-21 presented an occasion to formally address these, and a practical impetus for FHWA to partner with the other Agencies subject to the Uniform Act to again take a broad look at the Uniform Act to discuss their ideas on how implementation might be improved. The FHWA also used the rulemaking opportunity to review input on Uniform Act implementation issues that it has been collecting and compiling over recent years. Each of these sources of final changes to 49 CFR 24 are discussed below.

Section 1521 of MAP-21 included increases in certain relocation assistance benefit levels for displaced persons; the authority to develop a regulatory mechanism to consider and implement future adjustments to those benefit levels; and a requirement for an annual report on governmentwide real property acquisitions subject to the Uniform Act. Specifically, MAP-21:

Amended the maximum statutory benefit for replacement housing payments (RHP) for displaced homeowners from $22,500 to $31,000.

Amended the maximum statutory benefit for rental replacement housing payment (RRHP) for displaced tenants from $5,250 to $7,200.

Reduced the length of occupancy requirement for homeowners to be eligible for replacement housing payments from 180 days to 90 days before the initiation of negotiations.

Amended the maximum statutory benefit for reimbursement of business re-establishment expenses from $10,000 to $25,000.

Amended the maximum amount for the fixed “in-lieu-of moving costs” payment for non-residential displacements from $20,000 to $40,000.

Allows that if the head of the Lead Agency determines that the cost of living, inflation, or other factors indicate the relocation assistance benefits should be adjusted to meet the policy objectives of the Uniform Act, that the head of the Lead Agency may adjust certain benefit levels.

This final rule includes increases in certain benefits by roughly 33 percent to account for inflation and other factors since 2012. This was determined by using the most current Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) available, June 2023, compared to the end of year CPI for 2012 (305.1 / 229.6 = 1.33). Specifically, the final rule:

Amends the maximum statutory benefit for RHPs for displaced homeowners to $41,200.

Amends the maximum statutory benefit for RRHPs for displaced tenants to $9,570.

Amends the maximum statutory benefit for reimbursement of business re-establishment expenses to $33,200.

Amends the maximum amount for the fixed “in-lieu-of moving costs” payment for non-residential displacements to $53,200.

The MAP-21 also required that Federal Agencies that are subject to the Uniform Act, and have programs or projects requiring the acquisition of real property, or causing a displacement from real property to provide FHWA, as Lead Agency, with an annual summary report describing its Uniform Act activities. The previous requirement was that Agencies provide a report (49 CFR 24.9I) not more than every 3 years. The FHWA invited all the affected Federal Agencies to discuss the new reporting requirement. A working group consisting of a cross-section of affected Federal Agencies collectively developed language for 49 CFR 24 and a proposed template for the detailed annual report. The FHWA believes that the NPRM provides Agencies with a streamlined reporting format that balances the need to provide Agencies with appropriate time to develop the necessary reporting systems from which details can be extracted, with the need to compile the information into a meaningful report. Understanding that it may be unworkable for an Agency to complete a detailed report in the first year or during the course of successive years, the group agreed that an interim narrative report option where the Agency summarizes its Uniform Act stewardship and oversight efforts and detailed its progress toward being able to provide a detailed annual report would be appropriate.

The FHWA actively engaged other Agencies to identify other potential regulatory improvements. Immediately after MAP-21 was enacted, FHWA began outreach to the other Federal Agencies subject to Uniform Act requirements.

First, FHWA assembled a working group of approximately 25 Federal Agency representatives to discuss the regulatory amendments that MAP-21 required and other clarifications or modifications that might streamline implementation for practitioners and recipients. From November 2012 to April 2013, FHWA conducted a series of 10 conference calls with the working group. Together, the group reviewed 84 sections of 49 CFR 24 to discuss suggestions on how provisions of the regulation should be updated, clarified, or improved, as well as rationales for each revision. Contributions from working group members were based on their experiences implementing the rule and feedback they had received from their stakeholders. The FHWA considered the group’s recommendations for each of the regulation’s subparts and then convened a second Federal working group to discuss a vetted list of proposed changes. The second group met via 7 conference calls between April and June 2013 to review the list of proposed changes, ultimately identifying approximately 50 items it believed should be advanced in a rulemaking.

In October 2017, FHWA reconvened the Federal interagency working group representatives in a series of 10 meetings between November 8, 2017, and February 6, 2018, to again review the draft NPRM.

Between February and March of 2020, FHWA held NPRM listening sessions. The FHWA held two internal listening sessions, and four were held for the public to include State DOTs, local public agencies, the American Association of State Highway Transportation Organization, the International Right of Way Association and other Federal Agency funding recipients.

The FHWA has collected input and recommendations on Uniform Act implementation in the years since the last rulemaking. Field-level suggestions for improvement have come from direct practitioner comments and views expressed to FHWA and research projects that the Agency has funded.

Practitioner Input

Practitioners periodically contact FHWA to express confusion over certain sections of the regulation. They do so via communication with FHWA Division Offices or FHWA program office responsible for the Uniform Act; conversations at national conferences and symposiums co-sponsored by FHWA; feedback on FHWA pilot projects; and research designed to determine the effect of making changes to various Uniform Act requirements and procedures.

Research

The FHWA has used information from several recent research studies to further assess the adequacy of the current benefit levels. Several of the studies and their outcomes are discussed below.

Business Relocation Assistance Retrospective Study (BRARS)

A 2006 GAO report found evidence that displaced business owner interviewees considered Uniform Act benefits available to business to be inadequate.6 From 2010 to 2012, FHWA commissioned a study of the actual costs businesses incur as a result of having to relocate for a public transportation project. The primary focus of the research was to determine the costs that a business incurs that would be reimbursable if re-establishment expense payments were not limited to the existing Federal statutory maximum amount of $10,000. The FHWA had heard anecdotal evidence for many years that the payments were not adequate to re-establish a business. The study also investigated a fixed payment (payment in-lieu-of the re-establishment and other move cost benefits) a business may be eligible to receive, if not for the statutory maximum payment of $20,000.

A Study of Reverse Mortgages in Relocation Assistance

The FHWA commissioned a research effort focused on establishing a fair and effective method of calculating benefit payments available under the Uniform Act, when displacing persons with a reverse mortgage, also referred to as HECM. A reverse mortgage is a valid lien and is secured by the residence. However, unlike typical mortgages used to finance the dwelling, reverse mortgages allow the owner to withdraw some of the equity in their homes while still residing in them and to remain in the dwelling until either the owner passes away or decides to move from the dwelling. The research concluded that displacing owners whose property is encumbered with a HECM presents a number of challenges that do not fit neatly within the parameters of the Uniform Act or its implementing regulations. It recommended that when dealing with displacements involving homeowners with a HECM, each situation must be approached on a case-by-case basis, depending on the individual circumstances presented. Based on these report findings and FHWA’s programmatic experience, FHWA agrees that the Uniform Act, its implementing regulations, and current guidance do not adequately support determinations of benefits to be provided for displaced persons with a reverse mortgage. The final rule includes a new section, 24.401(e), that specifies how practitioners should calculate benefits for displaced homeowners who have reverse mortgages.

Electronic Notices and Offers

Currently, 49 CFR 24 requires that Agencies personally deliver or send notices to property owners or occupants by certified or registered first-class mail, return receipt requested. The FHWA sponsored a research project7 to evaluate the feasibility of using electronic methods to deliver notices and offers without jeopardizing an owner’s or a tenant’s rights under the Uniform Act. The research included interviews with State DOT personnel regarding their experience with electronic notices and the convening of a working group to identify the challenges that must be addressed when using an electronic delivery or signature verification system for federally funded projects. Findings suggested that, although personal contact and delivery is the preferred approach, the flexibility to use electronic delivery and signature verification would offer streamlining opportunities at various points throughout the right of way acquisition process. The research team recommended that FHWA:

Update the Uniform Act regulations to permit Agencies the flexibility to implement electronic delivery/signature verification systems for notices and offers and to allow methods of mail delivery other than the U.S. Postal Service.

Implement minimum safeguards or a certification process that allows the use of electronic notices or signatures consistent with existing State and Federal laws.

The FHWA published the NPRM in December 2019. Subsequent to the NPRM, FHWA responded to additional input from those Federal Agencies, recipients, and other members of the public. The final rule reflects that input and incorporates the following changes:

The final rule adds reimbursement of costs for rental replacement dwelling application fees and credit reports.

The final rule adds flexibility on how payments for self-moves (both residential and non-residential) can be calculated.

The final rule adds additional flexibility on when waiver valuations can be used.

The final rule has added flexibility on when certain limits and benefit payments can be adjusted for inflation and other factors. The proposed rule had proposed that such adjustments occur only after 5 years.

The final rule clarifies which payment limits can be adjusted in the future for inflation and other factors.

This regulatory evaluation is largely similar to the regulatory evaluation of the NPRM. However, it has been revised to reflect changes in the final rule compared to the NPRM (as summarized above) and to update the analysis given that roughly 3 years have passed since the analysis conducted for the NPRM. No public comments were received related to the RIA for the NPRM.

All acquiring Agencies meeting the definition set out in Section 24.2(a)(i) are required to comply with the Uniform Act and the implementing regulation, 49 CFR Part 24. The FHWA identified the 14 departments and 5 independent Agencies listed in Table 1 as being potentially subject to the Uniform Act. Of these, seven departments and three independent Agencies were found to not have active programs. Some active departments have multiple sub-agencies, or modes in the case of DOT, that administer separate Uniform Act Programs. Based on outreach to other Agencies conducted as part of this rulemaking, FHWA analysts believe that FHWA has the largest Uniform Act Program. However, other Agencies have sizable programs as well. Table 1 provides a list of the Uniform Act Agencies and their active status.

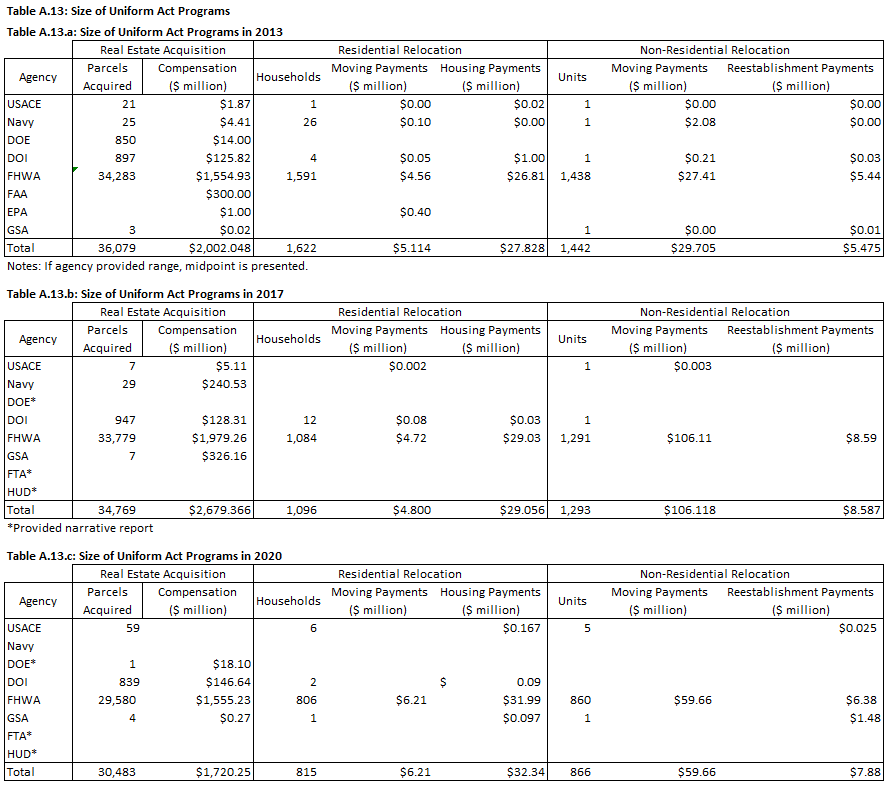

As part of the interagency coordination to develop this rulemaking in 2013, some Agencies provided data on the size of their respective programs, which is presented in Table A13, Appendix A of this report. However, since that effort represented the first time that this data had been assembled, the figures may not have been complete. More recently, Agencies have begun to report on their Uniform Act activities in compliance with MAP-21 and in anticipation of this rulemaking. The more current information is also presented in Table A13 of Appendix A of this report. Again, due to the still developing nature of Agency reports the figures may not be complete. Some of the Agencies have provided a narrative report rather than a numeric report.

In this analysis, the costs of the final rule are estimated for all Federal Agencies that are subject to the Uniform Act. However, due to data limitations, the benefits (where quantifiable) are estimated only for FHWA. The magnitude of transfers is also estimated only for FHWA due to data limitations. The MAP-21 requirement (further clarified in this final rule) for annual summary reports of Uniform Act activity from Federal Agencies is expected to alleviate these types of data issues going forward.

Table 1. Federal Agencies Potentially Subject to the Uniform Act

Department |

Status |

Department of Agriculture (USDA) |

|

Rural Utilities Service (RUS) |

Not Active |

U.S. Forest Service (FS) |

Active |

Department of Commerce |

Not Active |

Department of Defense (DOD) |

|

U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) |

Active |

U.S. Navy |

Active |

Department of Education |

Not Active |

Department of Energy (DOE) |

|

Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) |

Active |

Southwestern Power Administration (SWPA) |

Active |

Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) |

Active |

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

Not Active |

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) |

Active |

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

|

U.S. Coast Guard |

Not Active |

FEMA |

Active |

Department of Interior (DOI) |

|

Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) |

Active |

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) |

Active |

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) |

Active |

National Park Service (NPS) |

Active |

Department of Justice (DOJ) |

Not Active |

Department of Labor |

Not Active |

Department of State |

Not Active |

Department of Transportation (DOT) |

|

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) |

Active |

Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) |

Active |

Federal Transit Administration (FTA) |

Active |

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) |

Active |

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

Not Active |

Independent Agencies |

|

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

Active |

General Services Administration (GSA) |

Active |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) |

Not Active |

United States Postal Service (USPS) |

Not Active |

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) |

Not Active |

The key elements used in framing this analysis are as follows:

Discount Rates: 7 percent and 3 percent8

Period of Analysis: 10 years from 20–3 - 2032

Monetary values expressed in 2021 dollars unless otherwise specified

Discounting calculations use 2021 as the base year

Expected inflation rate over analysis period: 2.3 percent9

Section 24.11 of the final rule allows the Lead Agency to adjust the maximum payment amounts for certain limits and benefits payments listed in Section 24.11(a) when it determines that, due to the effects of the cost of living, inflation, or other factors, those limits and benefits payments should be adjusted to meet the policy objectives of the Uniform Act. While the rule is flexible, allowing such adjustments to occur when necessary, this analysis explores a scenario with adjustments approximately every 2-3 years through the analysis period (2025, 2028 and 2031). The first adjustment after the final rule becomes effective makes an inflation adjustment assuming the base is June 2023, which set the payment levels for this final rule.

Displaced persons (both homeowners and tenants) are provided with relocation benefits and other assistance under the Uniform Act. All actual, necessary, and reasonable moving expenses are reimbursed. In addition, displaced homeowner and tenant occupants may be eligible for RHP or RRHP as applicable, to assist with purchasing or renting a comparable replacement dwelling.

Although MAP-21 changes to Uniform Act benefit levels were effective on October 12, 2014, there has been no corresponding update of the published rule. Under the current published version of the rule, the maximum RHP amount for 90-day homeowner to purchase a replacement dwelling is $22,500, and the final rule revises that amount to $41,200. For 90-day tenant occupants, the current maximum RRHP is $5,250, and the final rule revises that amount to $9,570. Under the current rule, homeowner occupants who have resided at the location for fewer than 180 days but more than 90 days are considered as 90-day tenant occupants and are eligible for the RRHP. Under the final rule, such homeowners would be documented as eligible for an RHP instead.

The FHWA is the only Agency to provide historical data for Uniform Act activity. For that reason, this analysis focuses only on FHWA data. Figure 1 shows historical FHWA data on the number of residential displacements for the previous 9 years (2013 to 2021).10 During that time FHWA provided Federal-aid funding to State DOTs that carried out an overall cumulative average of 1,488 residential relocations per year. Thus, this analysis assumes that on average 1,488 residential relocations will occur each year of the analysis period.

Figure 1. Residential Relocations (FHWA)

As required by MAP-21, Section 24.401 and Section 24.502 of the final rule raises the maximum amount for the RHP for homeowners (including mobile home owners) from $22,500 to $31,000, while Section 24.402 and Section 24.503 of the final rule raises the amount of rental assistance payment or down payment assistance for tenants (including renters of mobile homes) from $5,250 to $7,200. The FHWA further adjusted the maximum amount by roughly 33 percent to account for inflation since 2012. This final rule raises the maximum amount for the RHP for homeowners to $41,200 and the rental assistance payment or down payment assistance for tenants to $9,570. Both payment amounts are increased by roughly 83 percent. The final rule allows for the maximum amount to be adjusted to account for cost of living, inflation, or other factors, which include unusual or historic escalation in property values, rental costs, or costs for other services necessary to relocate. These indicators and others will be considered in determining whether relocation assistance benefits should be adjusted to meet the policy objectives of the Uniform Act.

As will be discussed more fully below, the increases in RHP and RRHP are not expected to change program expenditures but instead will reduce certain recipient and Federal Agency administrative burdens. The reduced administrative burden is one benefit of the rule change.

To explain why this change is not expected to increase program expenditures, consider the fact that a federally funded public project cannot proceed until a person displaced from his/her dwelling has been provided relocation assistance, which ensures that a comparable dwelling is available. Housing replacement by a Federal Agency as a “Last Resort” (last resort housing provisions) in 42 U.S.C. 4626(b) provides that “No person shall be required to move from his or her dwelling on account of any program or project… unless…..comparable replacement housing is available….” Should comparable housing not be available within the statutory limits allowed for a tenant or homeowner, the last resort housing provisions of 42 U.S.C. 4626(a) require Agencies, on a case-by-case basis, to provide eligibilities and payments that exceed the statutory maximums to ensure that comparable replacement housing is available to displaced homeowner and tenant occupants.

The MAP-21 increase in statutory limits will reduce the incidence of having to utilize the last resort housing provisions of 42 U.S.C. 4626 and reduce the recipient and Federal Agency administrative burdens and costs that are associated with these payments. However, the total program expenditures will not change, since the current rule already requires that sufficient payment is provided to obtain replacement housing.

The last resort housing provisions were intended to ensure that Agencies have a mechanism for dealing with unique circumstances or extraordinary needs of displaced homeowner and tenant occupants. However, the nearly 20-year-old existing statutory limits result in the last resort housing provisions of 42 U.S.C. 4626 being frequently utilized. Thus, the effect of increasing the statutory limits will be to reduce the frequency and necessity of utilizing the last resort housing provisions. The use of last resort housing provisions creates additional administrative burdens for a displacing Agency, including the need for case-by-case documentation and justification by the Agency. Reduction in use of the last resort provisions and the administrative burdens associated with them will ensure that displacing Agencies provide needed benefits and assistance to displaced homeowner and tenant occupants in as timely a manner as possible.

The FHWA data shows that over the period 1991 to 2013 the percent of last resort housing residential relocations has been increasing at a rate of 0.8 percentage points per year (see Figure 2).11 The FHWA used this time period to understand baseline trends before the MAP-21 changes in maximum payment levels were adopted in practice. OMB Circular A-4 recommends agencies use a pre-statutory baseline for regulatory analysis.

Figure 2. Last Resort Housing as a Percent of All Residential Displacements (FHWA)

In 2009, FHWA contacted a number of entities to determine what displacing Agency administrative effort and costs are specifically associated with last resort claims. The majority of those contacted were able to provide an estimate of the amount of administrative time typically spent on developing both a written justification for use of last resort housing payments and the administrative effort expended to review and approve the payment claim. Analysis of the information provided indicates that on average a last resort housing claim requires approximately an additional 1.5 hours of displacing Agency administrative time for review and approval.

The average hourly wage for managers in State government for 2021 is $47.69.12 To account for the cost of employer provided benefits, we multiply the wage rate by a factor of 1.56 to arrive at $74 savings for each hour administrative time saved due to the final rule.13

To estimate the cost savings related to reduced displacing Agency administrative time needed for use of last resort housing payments due to the final rule, we estimated the change in the number of residential relocations using last resort housing payments due to the final rule each year during the analysis period. We then multiplied that number by 1.5 hours of administrative time reduction, and then multiply by $74 per hour (the cost savings related to one hour in administrative work.)

Table A7 of Appendix A of this report shows the calculations related to this estimation process. It is assumed that on average 1,488 residential relocations will occur each year of the analysis period. Under the current rule, we expect that the percent of residential relocations using last resort housing payments will continue to grow at 0.8 percentage points per year as shown in Figure 2. Following that trend, the percent using last resort would reach about 51 percent by 2023. However, as a result of the higher statutory limits in the final rule, we expect that the percent of relocations using the last resort housing payment would decrease. While there is uncertainty regarding the magnitude of the expected drop, an estimate can be made by comparing the real value of the RHP maximum (in constant 2021 dollars) to the percentage of last resort payments that would be predicted for that level of the RHP maximum.14 The final rule’s RHP maximum of $41,200 is roughly $36,174 in 2021 dollars ($41,200 * 0.878) (see column [d] of Table A15 in Appendix). In 1999, the RHP maximum of $22,500 in nominal dollars reaches a similar amount in 2021 dollars ($36,608) and the regression model suggests that roughly 32 percent of residential relocations used last resort during that year (see column [d] and [e] of Table A7). Therefore, we estimate that the percent using last resort housing payment in 2023 would drop from 51 percent in the baseline to 32 percent under the final rule. We assume that the percent of households receiving a last resort housing payment would then continue to grow at 0.8 percentage points per year until the amounts are adjusted for inflation or other factors.

The final rule is flexible, allowing such adjustments to occur when necessary, but this analysis explores a scenario with adjustments roughly every 2-3 years in the analysis period (2025, 2028 and 2031). As shown in Table A15, an analyst seeking to update the amounts in 2025 would calculate the factor by dividing the most recent CPI (for an adjustment in 2025, this analysis approximates using the CPI from 2024) by the CPI from June 2023. To estimate what the CPI would be in 2024, we use the most recent CPI available to us which is 305.1 for June 2023 and adjust for one and a half more years of expected inflation, whiIe the Presidents FY 23 Budget puts at 2.3 percent per year.15 As shown in Table A15, the resulting factor is 1.03 (305.1/ 315.7). Therefore, we assume that an adjustment made in 2025 would result an adjustment of 3 percent such that the RHP for homeowners would rise to $42,436 and the RRHP would rise to $9,857. Expressed in 2021 dollars, those amounts are $36,410 and $8,457 respectively. At that time, we expect that the percent of households receiving last resort housing payments drop to the predicted level 1999 levels when a similar level of payment (in real terms) was in place (see Table A7). That percentage is roughly 32 percent. The subsequent inflation adjustments will remain minor if they are done fairly regularly to keep up with inflation and each subsequent inflation adjustment will move the percent of households receiving last resort payments back to its 1999 level.

These calculations suggest that between 286 and 381 fewer households would receive last resort housing payments per year resulting in between 429 and 571 fewer hours spent in administering the program. When valued at $74 per hour, summed over the 10 year analysis period and discounted at 7 percent, this provision of the final rule provides roughly $236,000 of administrative cost savings. The estimated cost savings of raising the RHP in the final rule are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Benefits from Increasing Maximum Amounts for Replacement Housing Assistance (FHWA)

Year |

Administrative Cost Savings (2021 $) |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

2023 |

$31,712 |

$27,699 |

$29,892 |

2024 |

$31,712 |

$25,887 |

$29,021 |

2025 |

$34,355 |

$26,209 |

$30,524 |

2026 |

$34,355 |

$24,495 |

$29,635 |

2027 |

$34,355 |

$22,892 |

$28,772 |

2028 |

$38,319 |

$23,863 |

$31,157 |

2029 |

$38,319 |

$22,302 |

$30,249 |

2030 |

$38,319 |

$20,843 |

$29,368 |

2031 |

$42,283 |

$21,495 |

$31,463 |

2032 |

$42,283 |

$20,088 |

$30,546 |

Total* |

$366,012 |

$235,772 |

$300,627 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding |

|||

The use of the last resort housing provision has resulted in displaced homeowners and tenants receiving RHPs at amounts comparable to or exceeding the amounts in the final rule. Therefore, the statutory increases will not result in an increase of RHP eligibilities, payments, or reimbursements to displaced homeowners or tenants.

The final rule (Section 24.2(a)) widens the pool of homeowners eligible for an RHP by reducing the amount of time that a person must have owned and occupied the dwelling from 180 days to 90 days in order to be eligible. The final rule does not change the eligibility requirement for tenants; tenants who have resided at the location for 90 days or more are already eligible for a rental assistance payment under the current rule. Under the current rule, homeowners who have resided at the location for fewer than 180 days but more than 90 days are considered as 90-day tenants and are eligible for a replacement assistance payment.

Reduced displacing Agencies administrative burden is a positive impact of this rule change. Under the final rule, the group of homeowners who have resided at the displacement location for between 90 and 179 days would be eligible for replacement assistance payment up to a maximum amount of $41,200. Previously this group was eligible for a rental assistance payment of up to $5,250. By reducing the length of occupancy requirements for this subset of homeowners, an entire section of regulatory requirements focused on this specific calculation has been eliminated. The total program expenditures for RHPs for these homeowners is consequently expected to increase, but the final rule will reduce the administrative burden involved in determining payment amounts for this subset of homeowners.

It is assumed that on average 1,488 residential relocations will occur each year of the analysis period. The FHWA data indicates that over the period 1991 to 2003 on average 54 percent of residential relocations involve homeowners (rather than tenants). Therefore, we assume that there are 804 residential relocations of homeowners each year of the analysis period. Data from the 2013 American Housing Survey (most recent year for which data is available) shows that 5.28 percent of homeowners (this does not include tenants) had lived at their residence for less than 1 year. Assuming a uniform distribution of when homeowners moved into their residence (90 days / 365 days = ¼ or one quarter of the year), approximately 1.3 percent (5.28/4) had lived at their residence between 90 and 179 days.16 Given this, we assume that approximately 10 homeowner relocations will be impacted by the change in eligibility from 180 days to 90 days. We expect that by simplifying the calculations that pertain to this group there will be an administrative cost savings of 1.5 hours per instance for displacing Agencies. Thus, we estimate the total cost savings, valued at $74 per hour, would be approximately $11,100 over the analysis period (see Table 3).

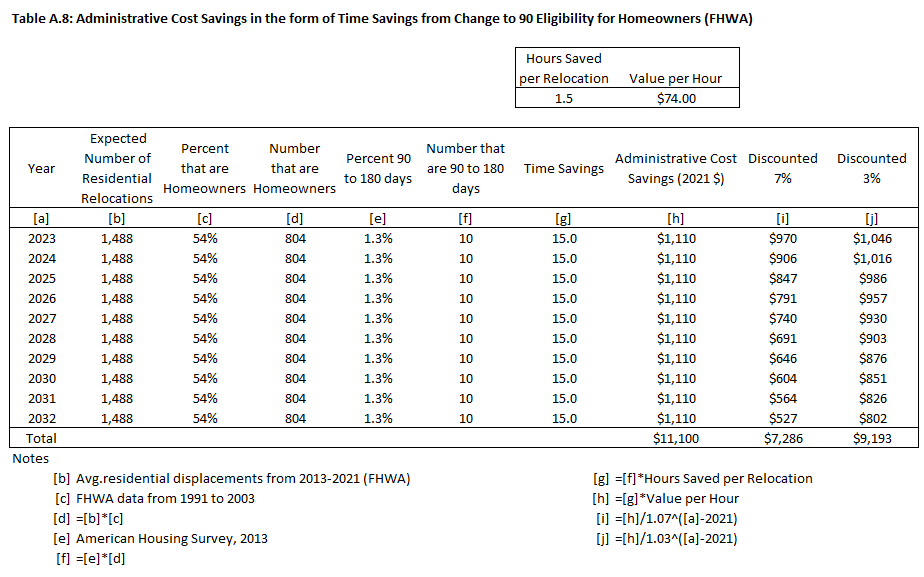

Table A8 in Appendix A of this report provides the details of this calculation.

Table 3. Administrative Cost Savings from Changing Homeowner Eligibility from 180 days to 90 days (FHWA)

Year |

Administrative Cost Savings (2021 $) |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

2023 |

$1,110 |

$970 |

$1,046 |

2024 |

$1,110 |

$906 |

$1,016 |

2025 |

$1,110 |

$847 |

$986 |

2026 |

$1,110 |

$791 |

$957 |

2027 |

$1,110 |

$740 |

$930 |

2028 |

$1,110 |

$691 |

$903 |

2029 |

$1,110 |

$646 |

$876 |

2030 |

$1,110 |

$604 |

$851 |

2031 |

$1,110 |

$564 |

$826 |

2032 |

$1,110 |

$527 |

$802 |

Total* |

$11,100 |

$7,286 |

$9,193 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding |

|||

This subset of displaced homeowners may receive some additional RHP as a result of this change. At most, program expenditures might increase by $31,630 per instance (the new maximum of $41,200 minus the old maximum of $9,570, if they were to remain only eligible for a rental assistance payment). However, we note that since they bought their home within 6 months of the displacement, the housing market in their area is likely not significantly different from the time they bought their home and the payment received for their property is likely to be sufficient to obtain comparable replacement housing with little additional program expenditure required.

In 2013, 1.3 percent of homeowners had lived at their residence between 90 and 179 days. Applying this 1.3 percent to the annual estimate of 804 residential relocations of homeowners each year suggests that 10 relocations per year may now be subject to the higher maximum payments and result in additional program expenditures of up to $31,630 per instance (in nominal dollars) or $27,771 (in 2021 dollars) in the first year of the analysis period.

In order to bring those estimates forward through the analysis, we must account for the fact that prices are changing over that period due to inflation. The final rule is flexible, allowing such adjustments to occur when necessary, but this analysis explores a scenario with adjustments roughly every 2-3 years in the analysis period (2025, 2028 and 2031). As shown in Table A15, an analyst seeking to update the amounts in 2025 would calculate the factor by dividing the most recent CPI (in 2025, the most recent CPI would be approximated from 2024) by the CPI from June 2023. To estimate what the CPI would be in 2024, we use the most recent CPI available to us which is 305.1 for June 2023 and adjust for one and a half more years of expected inflation, while the Presidents FY 23 Budget puts at 2.3 percent per year.17 As shown in Table A15, the resulting factor is 1.03 (315.7/ 305.1). Therefore, we assume that an adjustment made in 2025 would result an adjustment of 3 percent such that the RHP for homeowners would rise to $42,436 and the RRHP would rise to $9,857. Expressed in 2021 dollars, those amounts are $36,410 and $8,457 respectively.

Based on these calculations the difference in additional program expenditures (in 2021 dollars), between the current rule and the final rule would range between $26,000 and $27,800 in each year of the analysis period. These calculations are shown in Table A9 of Appendix A of this report.

Table 4. Transfers (Increased Program Expenditure) from Changing Homeowner Eligibility from 180 days to 90 days (FHWA)

Year |

Total Difference in Program Expenditures (2021 $) |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

2023 |

$277,711 |

$242,564 |

$261,770 |

2024 |

$271,385 |

$221,531 |

$248,356 |

2025 |

$273,338 |

$208,528 |

$242,857 |

2026 |

$267,148 |

$190,473 |

$230,444 |

2027 |

$261,284 |

$174,104 |

$218,821 |

2028 |

$273,302 |

$170,199 |

$222,220 |

2029 |

$267,028 |

$155,412 |

$210,794 |

2030 |

$261,101 |

$142,022 |

$200,112 |

2031 |

$273,036 |

$138,798 |

$203,164 |

2032 |

$267,068 |

$126,882 |

$192,936 |

Total* |

$2,692,401 |

$1,770,513 |

$2,231,474 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding

|

|||

A reverse mortgage, also known as a HECM is the Federal Housing Administration's Mortgage Program that enables seniors to withdraw some of the equity in their homes while still residing in them. Currently, the regulations do not address reverse mortgages and each instance is handled on a case-specific basis. The final rule adds a definition of reverse mortgage, identifying a reverse mortgage as a valid lien and describing common terms and conditions of the reverse mortgage. To supplement the definition, the final rule at Section 24.401(e) allows certain reverse mortgage expenses to be an eligible for reimbursement as a Mortgage Interest Differential Payment, and offers a new section to 49 CFR Appendix A at Section 24.401(e) with examples of types of reverse mortgages and benefit options. The goal of the change is to enable those homeowner occupants who have reverse mortgages 180-days prior to the initiation of negotiations to be made whole by providing them with reimbursement to purchase a replacement reverse mortgage when purchasing replacement housing.

Reverse mortgages allow older homeowners to draw down the equity of their home to provide income for daily living expenses, while at the same time remaining in their home. The final rule specifies that displaced homeowners who currently have the financial benefits and security of reverse mortgages, should be provided with a similar reverse mortgage after the relocation. Therefore, the benefit of the final rule is that the group of displaced homeowners who have a reverse mortgage retain the benefits of that reverse mortgage after the relocation. Currently, displacements on properties with reverse mortgages are relatively rare occurrences, but they may become more common in the future.

Obtaining new replacement reverse mortgages will likely require additional program expenditures but the magnitude of the increased program expenditures is unknown. At this time FHWA has only anecdotal experience with pricing replacement reverse mortgages. Reverse mortgages are complicated financial instruments and the calculations involved in pricing reverse mortgages are unique to each individual case and involve the age of the homeowner, the amount of remaining equity in the home, etc. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate the additional costs of obtaining replacement reverse mortgages.

Due to their complexity, there is expected to be an increase in recipient and Federal Agency administrative time required to facilitate reverse mortgages for displaced homeowners.

Based on FHWA 2013-2021 statistical data shown in Figure 1. Residential Relocations (FHWA), it is assumed that for FHWA, on average, 1,488 residential relocations will occur each year of the analysis period. The FHWA data indicates that over the period 1991 to 2003, on average, 54 percent of residential relocations involve homeowner occupants (rather than tenant occupants). Therefore, we assume there are 804 residential relocations of homeowners each year of the analysis period.

According to data from the 2021 American Housing Survey, approximately 1.8 percent of homeowners held a reverse mortgage in 2021.18 In the absence of information on expectations of future growth and/or contraction of the reverse mortgage market, we assume that the percent of homeowners holding reverse mortgages stays constant at 1.8 percent. We therefore assume that 14.5 (0.018*804) FHWA residential displacements would be encumbered by reverse mortgages each year of the analysis period. We use current information on the size of FHWA’s program relative to all Federal activity, as shown in Table A13.c of Appendix A and find that roughly 99 percent of all the known Uniform Act residential displacements in 2020 are attributed to FHWA (806 out of 815). Thus, we factor the FHWA estimate by 1.01 resulting in a governmentwide estimated total of 15 reverse mortgages.

We estimate that program specialists would spend 5 hours per parcel facilitating a replacement reverse mortgage. The average hourly salary for this type of State government worker is $37.94.19 By multiplying the hourly wage by 1.56 to account for the cost of employer-provided benefits, hourly costs become $59. These calculations are shown in Table A12 of Appendix A of this report and are summarized in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Administrative Costs of Reverse Mortgages (All Agencies)

Year |

Reverse Mortgage Administrative Costs (2021$) |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

2023 |

$4,425 |

$3,865 |

$4,171 |

2024 |

$4,425 |

$3,612 |

$4,050 |

2025 |

$4,425 |

$3,376 |

$3,932 |

2026 |

$4,425 |

$3,155 |

$3,817 |

2027 |

$4,425 |

$2,949 |

$3,706 |

2028 |

$4,425 |

$2,756 |

$3,598 |

2029 |

$4,425 |

$2,575 |

$3,493 |

2030 |

$4,425 |

$2,407 |

$3,391 |

2031 |

$4,425 |

$2,249 |

$3,293 |

2032 |

$4,425 |

$2,102 |

$3,197 |

Total* |

$44,250 |

$29,046 |

$36,647 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding

|

|||

In Section 24.301(g)(7), the final rule will add a new provision for reimbursement of costs for rental replacement dwelling application fees and credit reports for both residential and non-residential relocations.20 The additional benefit payment was proposed via a comment to the December 2019 publication of the NPRM for 49 CFR part 24 in the Federal Register. The comment brought to FHWA’s attention that residential tenant occupants may not be afforded reimbursement for rental application fees and costs for required inquiries into a displaced tenant’s application and credit history for the purpose of renting a replacement dwelling allowable under Section 4.301(g)(7). The FHWA determined that providing the eligibility as a moving related expense will provide displaced tenant occupants assurance of receiving reimbursement for this incidental expense, and will clarify the requirements for Agency implementation and utilization. The FHWA has included this expense with a capped amount of $1,000 (although in individual circumstances the cap can be raised by applying for a waiver for reasonable and necessary costs). Revisions in Section 24.11 will allow this cost cap to be increased in the future for inflation or other factors.

The benefits of this rule change relate to increased equity and fairness. The rule change will help to ensure that displaced persons shall not suffer disproportionate injuries as a result of programs and projects designed for the benefit of the public as a whole, and to minimize the hardship of displacement on such persons for programs or projects undertaken by a Federal Agency or with Federal financial assistance.

The FHWA anticipates that this rule change will result in increased program expenditures. The FHWA data indicates that the largest annual total of non-residential re-establishment claims processed between 1991 and 2003 was 750. For that same period, the largest total for residential tenants was 1,146, including last resort rental assistance payments and excluding 357 rental assistance payments used as down payments on the purchase of a replacement dwelling (the latter group, since they are purchasing a home, would not experience costs related to rental applications or credit checks).21 Since 10 percent of States prohibit fees being charged by landlords for rental applications and credit history, this estimate of increased program expenditures assumes that 90 percent of the rental replacement housing claims would incur this category of costs. The total number of expected displacements that may incur program costs associated with rental applications and credit checks is then 1,706.

While the maximum amount allowed for this category of reimbursement is $1,000, the actual average cost incurred is likely to be lower. The typical fee is roughly $50.22 Prospective tenants may need to apply to multiple properties, therefore this analysis assumes each displacement would involve four applications for a reimbursement of the $200 ($50 * 4) per displacement and a total across all displacements of $341,200 per year. These calculations are presented in Table A14 in Appendix A of this report and summarized in Table 6, below.

Table 6. Transfers (Increased Program Expenditures) from Reimbursing Rental Application and Credit Check Fees

Year |

Total

Difference in Program Expenditures |

Discounted 7% |

Discounted 3% |

2023 |

$341,200 |

$298,017 |

$321,614 |

2024 |

$341,200 |

$278,521 |

$312,246 |

2025 |

$341,200 |

$260,300 |

$303,152 |

2026 |

$341,200 |

$243,271 |

$294,322 |

2027 |

$341,200 |

$227,356 |

$285,750 |

2028 |

$341,200 |

$212,482 |

$277,427 |

2029 |

$341,200 |

$198,582 |

$269,346 |

2030 |

$341,200 |

$185,590 |

$261,501 |

2031 |

$341,200 |

$173,449 |

$253,885 |

2032 |

$341,200 |

$162,102 |

$246,490 |

Total* |

$3,412,000 |

$2,239,669 |

$2,825,733 |

*Totals may not match sums due to rounding

|

|||

In response to comments to the NPRM, FHWA revised the final rule related to payment for self-moves. The changes are found at Section 24.301(b)(2)(ii-iv) and Section 24.301(c)(2)(ii-iv). Subparagraph (ii) adds criteria needed to determine and document self-move reimbursement eligibility. Subparagraph (iii) adds new flexibility to allow use of a move cost estimate prepared by qualified Agency staff and subparagraph (iv) adds new flexibility to base residential self-move cost reimbursement eligibility on the lower of two commercial moving cost bids. Previously the self-move cost reimbursement was made based on a fixed schedule periodically published by FHWA or by documenting actual receipted expenses related to the self-move such as equipment rental and labor.

The flexibility to use a cost estimate prepared by qualified Agency staff is a benefit because its use will result in cost savings through reduced administrative burdens and paperwork for Agencies subject to the Uniform Act for low cost, uncomplicated personal property only moves as opposed to obtaining a commercial bid. These cost savings are not quantifiable as their use will be voluntary on the part of the Agencies, and a method for tracking the actual instances where this moving cost payment method will be used has not been established.

The flexibility to use the lower of two commercial bids is a benefit to Agencies subject to the Uniform Act and to the displaced person because it will provide a streamlining of the claim process for a self-move, since receipts will not be required as in the case of an actual cost self-move, resulting in reduced administrative burdens and paperwork. These cost savings are not quantifiable as their use will be voluntary on the part of the Agencies and displaced persons, and a method for tracking their actual use has not been established.

This change is not expected to change the amount of program expenditures to displaced persons.

The Uniform Act allows for two options for relocation assistance benefits to non-residential displacements.23 The first option allows for reimbursement of actual approved expenses related to search, re-establishment, and moving expenses. Under the current rule, the maximum reimbursable amount of search related expenses is $2,500. The final rule changes the maximum amount to $5,000. Non-residential displaced persons need to provide documentation related to those expenses in order to receive the reimbursement payment. However, the final rule also allows for a single payment of $1,000 with minimal or no documentation, as the total reimbursement payment for searching expenses should the displaced person select this option.

Moving expense payments are generally based on the lower of two estimates from a commercial moving service or a self-move based on actual receipts and an hourly pay rate. Documentation and verification of the move is required to receive this payment.

In addition to Agency approved moving costs, relocation assistance for non-residential displacements also allows for reimbursement of re-establishment expenses up to a maximum of $10,000; MAP-21 required an increase in the maximum amount to $25,000. The final rule increases the maximum amount to $33,200 to account for recent inflation. Eligible re-establishment expenses include such things as modification to the replacement property to accommodate the business operation and advertisement of the replacement location.

An alternative for non-residential displacements involves a fixed “in-lieu-of,” moving costs payment. Instead of submitting documentation related to relocation expenses (search, re-establishment, and moving), a non-residential displaced person can opt to receive a payment equal to its average annual net earnings over the last 2 years. The maximum amount for the in-lieu-of payment is $20,000 under the current rule. The final rule raises the maximum amount to $53,200 to account for recent inflation. The non-residential displaced person may choose only one option, either the reimbursement of moving costs, search expenses, and re-establishment expense payments or the in-lieu-of moving costs payment.

The final rule at Section 24.11 allows for the maximum amounts related to reimbursement for re-establishment expenses and the in-lieu-of moving costs payment to be adjusted for inflation or other factors. Table 7 provides a summary of these payment amounts.

Table 7. Non-Residential Maximum Payments

Payment Type |

Current Maximum |

Maximum Under Final Rule |

Reimbursement Option |

|

|

Search Expenses |

$2,500 |

$5,000; or $1,000 with little or no documentation |

Re-establishment Expenses |

$10,000 |

$33,200* |

Moving Expenses |

None |

None |

In-lieu-of Option |

|

|

Payment Amount |

$20,000 |

$53,200* |

*Can be adjusted for inflation or other factors.

|

||

The FHWA is the only Agency that had and could provide a significant amount of historical data for Uniform Act relocation activity. For that reason, this analysis focuses only on FHWA data. Figure 3. Non-Residential Displacements (FHWA) shows historical FHWA data on a number of non-residential displacements for the previous 9 years (2013 to 2021).24 During that time FHWA provided Federal-aid funding to State DOTs that carried out an average of 1,388 non-residential relocations per year. Thus, this analysis assumes that on average 1,388 non-residential relocations will occur each year of the analysis period.

Figure 3. Non-Residential Displacements (FHWA)

The FHWA data from 1991 to 2003 (see Figure 4) shows that during that time period approximately 14 percent of non-residential displacements received the in-lieu-of payment rather than the reimbursement payment. There is no discernable trend in that percentage during that period. It is possible that raising the maximum amount of the in-lieu-of payment will cause more displaced businesses to choose that option. However, there is insufficient information upon which to make an estimate of that impact. Therefore, we assume that 14 percent of business displacements will elect to receive the in-lieu-of payment during the analysis period both with and without the final rule.

Figure 4. Non-Residential In-Lieu-Of Payments (FHWA)

Section 24.301(g) allows non-residential displaced persons to be reimbursed for certain eligible actual moving expenses, including re-lettering of signs and replacing stationary. The final rule adds making updates to other media that are made obsolete as a result of the move to the list of eligible moving expenses. The FHWA intends in part for this change to cover the cost of making changes to Websites, DVDs, CDs, or other types of media that have been introduced since the implementing regulations of the Uniform Act were first written.

The benefits of the rule change will be increased fairness and equity. There may also be more non-residential displaced persons that would re-establish successfully because of the reduced costs of moving. Under the new rule, non-residential displaced persons can be reimbursed for expenses that they either currently absorb or perhaps choose not to incur.

The new payment is a reimbursement, and thus the resulting increase in payments is not a social cost, but rather a transfer. There is not sufficient information upon which to estimate the magnitude of the increase in program expenditures due to the final rule.

The current rule allows for reimbursement to non-residential displaced persons for reasonable expenses related to searching for a replacement location. The final rule at Section 24.301(g)(18) increases the maximum amount of reimbursement from $2,500 to $5,000, an increase of $2,500. The final rule at Section 24.301(g)(18)(ii) allows for non-residential displaced persons to be provided a one-time payment of $1,000 for search expenses as an alternative to the reimbursements provided for in Section 24.301(g)(18)(i) with little or no documentation. The change to Section 24.301(g)(18)(i) will allow these search expenses to include attorney’s fees related to negotiating the purchase of a replacement site. In response to comments received to the NPRM, the final rule at Section 24.11 allows for this amount to be adjusted for inflation or other factors in the future.