Study Design Year 2

Appx A_study design_poultry rinsing_3_9_18.docx

In-Home Food Safety Behaviors and Consumer Education: Annual Observational Study

Study Design Year 2

OMB: 0583-0169

Appendix A:

Detailed Study Description for Year 2 Study on the

Clean Message and Not Rinsing Raw Poultry

The purpose of the observational study is to evaluate adherence to the key behaviors of clean, separate, cook and chill following exposure to food safety messaging and to assess the extent of cross contamination in the kitchen due to failure to follow recommended practices. The purpose of the Year 2 observational study/meal preparation experiment is to evaluate adherence to the key behavior of “clean” following exposure to existing food safety messaging from USDA FSIS OPACE and to assess the extent of cross-contamination in the kitchen due to failure to follow recommended cleaning and sanitation practices.

For the Year 2 study, we will recruit individuals who self-report washing/rinsing chicken in their homes and randomly assign participants to either a control group (no exposure to food safety messaging) or an intervention (treatment) group. The intervention group will receive USDA FSIS OPACE “Clean” messages in a simulated social media stream by including these messages as part of the email scheduling process.

Three existing messages will be delivered to intervention participants via email; each message will be sent twice as part of the signature line of the NCSU scheduling team:

Message 1 (in Emails 1 and 3): Prepping dinner? Avoid cross-contamination! Use 2 separate cutting boards: 1 for produce & bread and 1 for raw meat, poultry, & seafood (with clean graphic).

Message 2 (in Emails 1 and 2): Why do we recommend NOT washing your meat & poultry? The answer is simple, it doesn’t destroy bacteria, it spreads it! Click here to learn more (with this URL to the poultry washing video and screen shot) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBeMcOvDoi8&app=desktop)

Message 3: (in Emails 2 and 3): DON’T WASH YOUR CHICKEN! Washing will spread bacteria & won’t even clean your bird! The only way to be safe is to cook your chicken to 165°F! #FoodSafety (with clean infographic)

We will send Email #1 to the participant on the same day his or her appointment is scheduled. We will send Email #2 five days before the participant’s scheduled appointment, and we will send Email #3 two days before the participant’s scheduled appointment. The control group will receive appointment reminders without the messaging.

We will provide participants with the ingredients needed to prepare a specific meal of baked chicken thighs. We selected bone-in, skin on chicken thighs because we believe individuals are more likely to wash this cut of poultry; additionally, thighs will take less cook time than breasts and whole birds. Initially, we will tell participants that they are testing a spice blend developed at NCSU, and we are interested in how the spices will be applied to chicken thighs.

Before the observation and food preparation, the chicken thighs will be inoculated with a traceable nonpathogenic E. coli strain (K-12 or DH5a), which behaves like Salmonella, tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Niebuhr et al., 2008). This surrogate and microbiological approach was cleared by FSIS’ Office of Public Health Science). We will begin video recording handling and meal preparation as soon as the participant enters the test kitchen and will end video recording after the participant leaves the test kitchen for the final time.

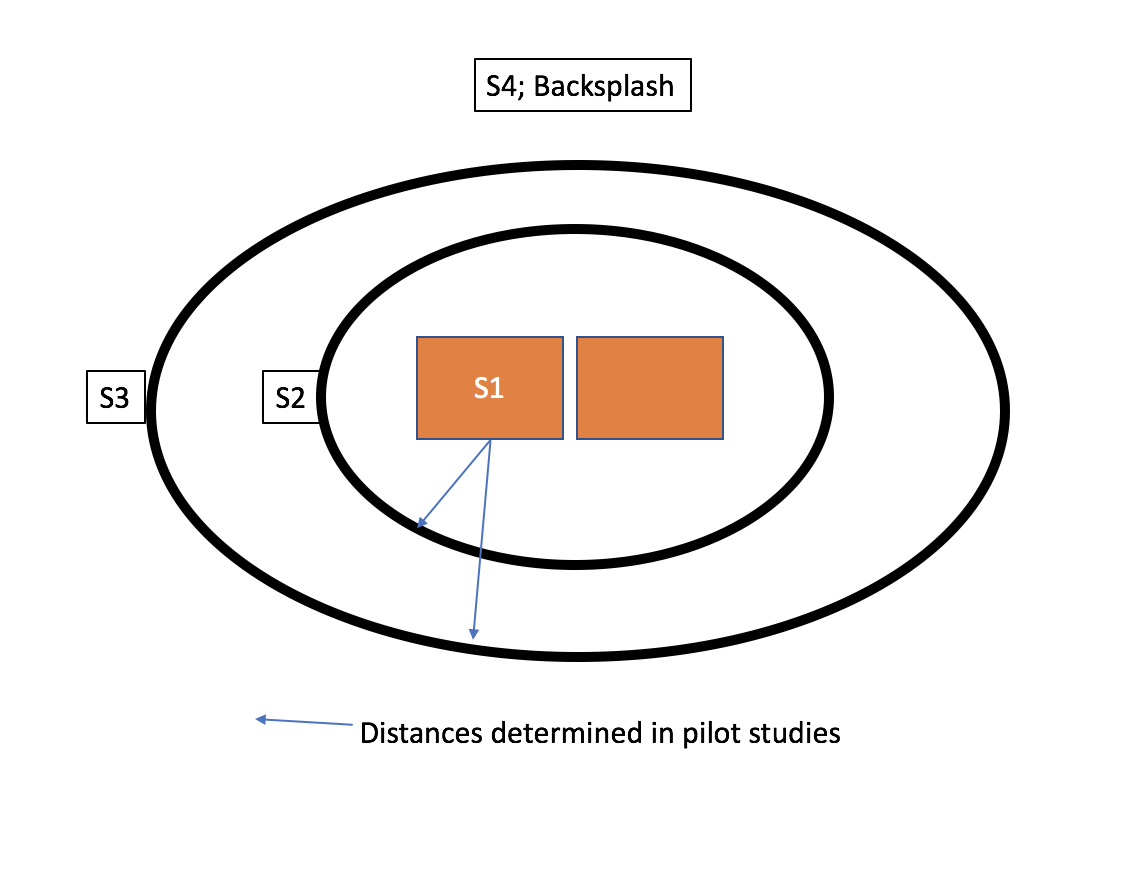

Participants will be instructed to prepare the chicken as they would at home using the new spice blend as seasoning. Participants will be instructed that part of the data collection will be taking a photo of the raw, seasoned chicken product. They will be asked to wait in the lobby area of the kitchens while the “photo” is taken. During this time, swabs will be taken from the inner sink, outer sink area 1, outer sink area 2, outer sink area 3 (exact radius to be determined in pilot testing but estimated to be 3 feet from the sink based on previous research [Everis & Betts, 2003; Henley et al., 2016]). Figure 1 illustrates the swabbing areas.

Participants will be instructed to reenter the kitchen and bake the chicken thighs for 25 minutes per the recipe instructions. While the chicken thighs are baking, participants will be asked to clean the kitchen as they would at home. Participants will leave the kitchen for the post-observation interview.

Following the observation portion of the study and after participants have cleaned up as they would at home, trained sample collectors will take surface swab samples from the inner sink (S5, or S1 “after”), and outer sink area 1 (S6, or S2 “after”) to gather data on participants’ cleaning/sanitizing efficacy. The swabs will be plated at an NCSU lab to determine presence and concentration of the nonpathogenic E. coli. The presence of the tracer will indicate that cross-contamination occurred during food preparation. The level of cross-contamination will be compared across the sampling sites to determine the highest risk areas. Kitchen surfaces, appliances, and other potentially contaminated sites will be cleaned and sanitized after each participant to ensure that any positive samples collected were a result of the participants’ behaviors.

Figure 1. Swabbing Areas to Measure Potential Cross-Contamination

We will use notational analysis to assess recorded chicken washing and cleaning and sanitizing actions and their frequencies. Notational analysis is a generic tool used to collect observed events and place them in an ordered sequence (Hughes & Franks, 1997); it has been used to track food safety behaviors, because it enables the recording of specific details about events in the order in which they occur by associating a time-stamp with actions (Clayton & Griffith, 2004). This method is especially useful when looking at sanitation steps limiting cross-contamination or the use of common food contact surfaces and equipment. Notational analysis has been used in both nonparticipant and participant consumer food safety behavior observation studies, as well as participant food service observation (Clayton & Griffith, 2004; Green et al., 2006; Redmond et al., 2004).

Supplementing the observations, we will conduct a post-observation interview to provide insight into participants’ views, opinions, and experiences of their preparation practices of these products and to collect information on behaviors that we were unable to observe (e.g., storage of leftovers or thawing) and conduct a content analysis of participant responses. Content analysis provides a means of adapting qualitative (in this case, interview) data into quantitative data to allow for comparison across groups through a consistent and validated coding scheme. Collecting qualitative data will allow the project team to connect the knowledge, attitude, and perceived behavior with actual observed practices, allowing for a more targeted intervention development. The results of these interviews, coupled with observation, will serve as the foundation for message development and delivery.

References

Clayton, D. A., & Griffith, C. J. (2004). Observation of food safety practices in catering using notational analysis. British Food Journal, 106(3), 211–227.

Everis, L. & Betts, G. (2003). Microbial risk factors associated with the domestic handling of meat: sequential transfer of bacterial contamination. R&D Report No. 170. Chipping Campden, UK: Campden BRI.

Green, L. R., Selman, C. A., Radke, V., Ripley, D., Mack, J. C., Reimann, D. W., … Bushnell, L. (2006). Food worker hand washing practices: An observation study. Journal of Food Protection, 69, 2417–2423.

Henley, S., Gleason, J., & Quinlan, J. (2016). Don’t wash your chicken!: A food safety education campaign to address a common food mishandling practice. Food Protection Trends, 36, 43–53.

Hughes, M., & Franks, I. (1997). Notational analysis of sport. London: E. & F. N. Spon.

Niebuhr, S. E., A. Laury, G. R. Acuff, and J. S. Dickson. 2008. Evaluation of nonpathogenic surrogate bacteria as process validation indicators for Salmonella enterica for selected antimicrobial treatments, cold storage, and fermentation in meat. Journal of Food Protection, 71, 714–718.

Redmond, E. C., Griffith, C. J., Slader, J., & Humphrey, T. J. (2004). Microbiological and observational analysis of cross-contamination risks during domestic food preparation. British Food Journal, 106(8), 581–597.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Barrell, Sharon M. |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-21 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy