Task29_OMB_PartB_August 2016

Task29_OMB_PartB_August 2016.docx

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs

OMB: 1875-0280

OMB Clearance Request:

Part B – Appendices (DRAFT)

Study

of Title I Schoolwide and

Targeted Assistance Programs

PREPARED BY:

American

Institutes for Research®

1000 Thomas Jefferson

Street, NW, Suite 200

Washington, DC 20007-3835

PREPARED FOR:

U.S. Department of Education

Policy and Program Studies Service

August 2016

OMB

Clearance Request

Part B

August 2016

Prepared

by: AIR

1000 Thomas Jefferson Street NW

Washington, DC

20007-3835

202.403.5000 | TTY 877.334.3499

www.air.org

Contents

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs 2

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission 6

Description of Statistical Methods 6

2. Procedures for Data Collection 13

3. Methods to Maximize Response Rate 19

4. Expert Review and Piloting Procedures 20

Introduction

The Policy and Program Studies Service (PPSS) of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance for data collection activities associated with the Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs. The purpose of this study is to provide a detailed analysis of the types of strategies and activities implemented in Title I schoolwide program (SWP) and targeted assistance program (TAP) schools, how different configurations of resources are used to support these strategies, and how local officials make decisions about the use of these varied resources. To this end, the study team will conduct site visits to a set of 35 case study schools that will involve in-person and telephone interviews with Title I district officials and school staff involved in Title I administration. In addition, the study team will collect and review relevant extant data and administer surveys to a nationally representative sample of principals and school district administrators. Both the case study and survey samples include Title I SWP and TAP schools.

Clearance is requested for the case study and survey components of the study, including its purpose, sampling strategy, data collection procedures, and data analysis approach. This submission also includes the clearance request for the data collection instruments.

The complete OMB package contains two documents and a series of appendices as follows:

OMB Clearance Request: Part A – Justification

OMB Clearance Request: Part B – Statistical Methods [This Document]

Appendix A.1 – District Budget Officer Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix A.2 – District Title I Coordinator Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix B – School Budget Officer Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix C – School Improvement Team (SWP School) Focus Group Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix D – School Improvement Team (TAP School) Focus Group Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix E – Principal (SWP School) Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix F – Principal (TAP School) Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix G- Teacher Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix H – Principal Questionnaire

Appendix I – District Administrator Questionnaire

Appendix J – Request for Documents

Appendix K – Notification Letters

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs

Project Overview

Title I’s schoolwide program (SWP) provisions, introduced in 1978, gave high-poverty schools the flexibility to use Title I funds to serve all students (not just students eligible for Title I) and to support whole-school reforms. Unlike the traditional targeted assistance programs (TAPs), SWP schools also were allowed to commingle Title I funds with those from other federal, state, and local programs and were not required to track dollars back to these sources or track the spending under each source to a specific group of eligible students. Initially aimed at schools with a student poverty rate of 90 percent or more, successive reauthorizations have reduced the poverty rate threshold for schoolwide status to 50 percent in 1994 and 40 percent in 2001 under No Child Left Behind. In a change from previous acts, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), enacted in December 2015, further allows states to approve schools to operate an SWP with an even lower poverty percentage. In response to these changes, the number and proportion of schools that are SWPs has increased dramatically over time. In the most recent year for which data are available (2013–14), 77 percent of Title I schools nationwide were SWPs.1 The ESSA allowance for states to authorize SWPs in schools with a lower than 40 percent poverty is likely to result in an even greater number of schools operating as SWPs.

In exchange for flexibility, SWPs are required to engage in a specified set of procedures. First, a schoolwide planning team must be established, charged with conducting a needs assessment grounded in a vision for reform. The team must then develop a comprehensive plan that includes prioritizing effective educational strategies and evaluating and monitoring the plan annually using empirical data. Implicit in these provisions is a vision that SWPs will engage in an ongoing, dynamic continuous improvement process and will implement systemic, schoolwide interventions, thus leading to more effective practices for low-income students. Yet little is known about whether SWPs have realized this vision.

This study will conduct a comparative analysis of SWP and TAP schools to look at the school-level decision-making process, implementation of strategic interventions, and corresponding resources that support these interventions. Comparing how SWP and TAP schools allocate Title I and other resources will provide a window into the different services that students eligible for Title I receive. For example, prior research shows that SWPs are more likely than TAP schools to use their funds to support salaries of instructional aides (U.S. Department of Education [ED], 2009). In addition, a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report concluded that school districts use Title I funds primarily to support instruction (e.g., teacher salaries and instructional materials) (GAO, 2011), as did an earlier study of Title I resource allocation (ED, 2009). However, such data are not sufficient to show how decisions related to educational strategies and resource allocation are made, and what services and interventions these funds are actually supporting. This study will provide a better understanding of how SWP flexibility may translate into programs and services intended to improve student performance by combining information from several sources, including reviews of school plans and other relevant extant data, case study interviews, and surveys.

Through this study, the research team will address these three primary questions:

How do schoolwide and targeted assistance programs use Title I funds to improve student achievement, particularly for low-achieving subgroups?

How do districts and schools make decisions about how to use Title I funds in schoolwide programs and targeted assistance programs?

To what extent do schoolwide programs commingle Title I funds with other funds or coordinate the use of Title I funds with other funds?

To address the research questions, this study includes two primary types of data collection and analysis, each of which consists of two data sources:

Case studies of 35 schools, which include interviews with district and school officials as well as extant data collection

Nationally representative surveys of Title I district coordinators and principals of SWP and TAP Title I schools

Conceptual Approach

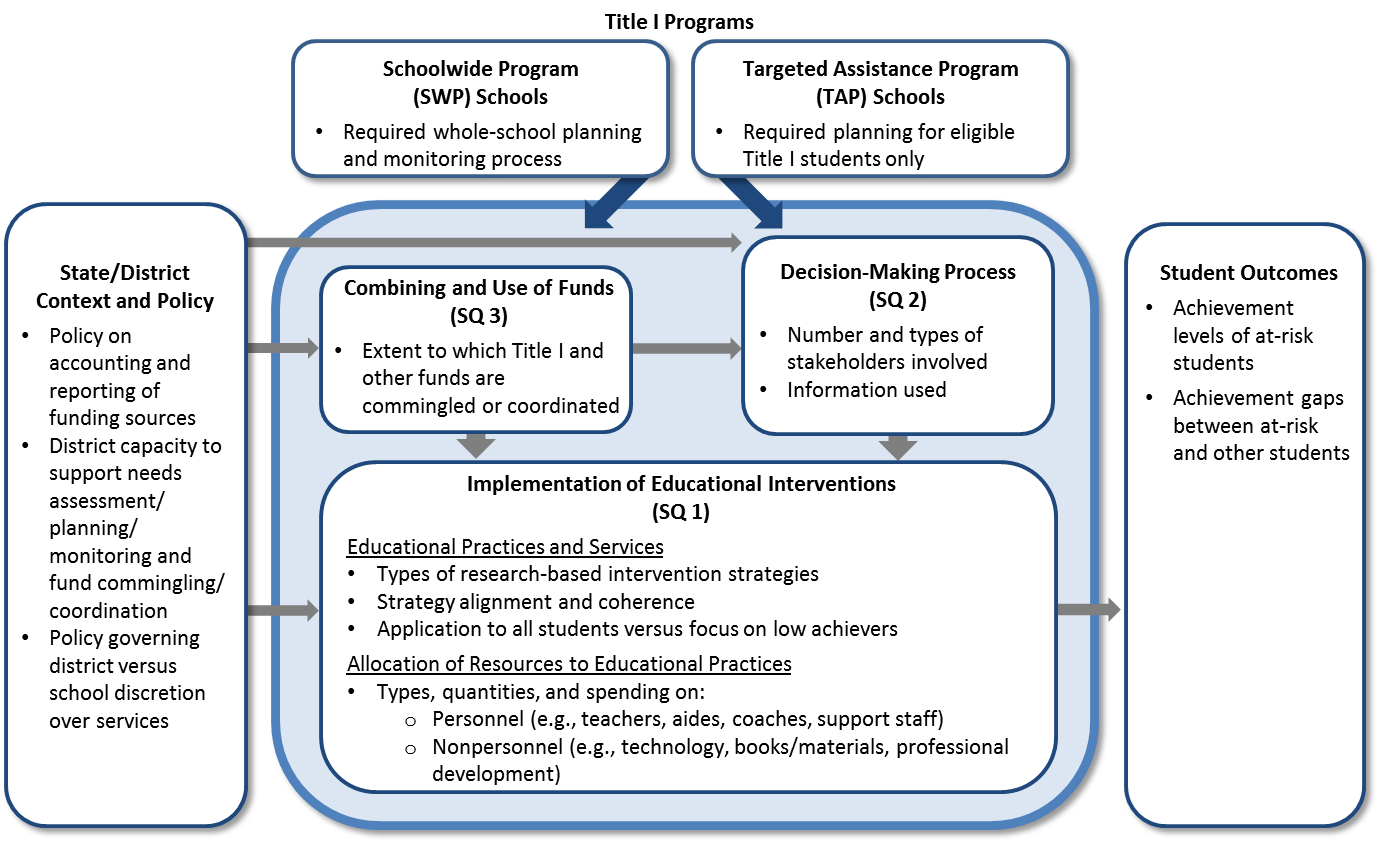

The focus of this study is the complex interplay among school decision making, use of funds, and implementation of educational practices, depicted in the central part of Exhibit 1. Two key policy levers may contribute to differences between SWP and TAP Title I schools: planning requirements and funding flexibility.2 Based on a needs assessment grounded in the school’s vision for reform, SWPs must develop an annual comprehensive plan in which they set goals and strategies, and monitor outcomes of all students through an annual review. TAP schools, conversely, are required to identify Title I–eligible students, target program resources to this group, and annually monitor their outcomes separately from the noneligible students. The policy also treats SWP versus TAP schools differently in terms of how each can use their program funding, the accounting/reporting requirements, and the regulatory provisions to which they must adhere. SWPs may commingle Title I funds with other sources of federal, state, and local funding, while TAPs may not. Moreover, for SWPs both reporting requirements and the applicability of statutory/regulatory provisions are relaxed provided that schools can show that the program funding spread over the entire school’s enrollment was spent on intervention strategies that align with the intentions of Title I, which is not the case for TAP schools.

These policy provisions are intended to enable SWPs to design the types of educational programs that, according to decades of research on school improvement, are more likely to benefit students. Studies from the 1980s onward have identified characteristics associated with schools that are successful (particularly for disadvantaged students): shared goals, positive school climate, strong district and school leadership, clear curriculum, maximum learning time, coherent curriculum and instructional programs, use of data, schoolwide staff development, and parent involvement (Desimone, 2002; Fullan, 2007; Purkey & Smith, 1983; Williams et al., 2005). The extent to which SWP and TAP schools use Title I funds to support these kinds of practices—designing coherent whole-school programs with these characteristics, identifying and comingling or coordinating multiple funding streams, and selecting appropriate interventions and practices—is the focus of this study.

Title I requirements and guidance encourage SWPs to engage a greater variety of individuals in a more extensive planning process, rely on more complete schoolwide data sources, and engage in more frequent ongoing monitoring of progress than TAP schools. Research suggests that engagement of a range of school personnel and other stakeholders enhances a school’s decisions about strategies to undertake and commitment to the schoolwide program (Mohrman, Lawler, & Mohrman, 1992; Newcombe & McCormick, 2001; Odden & Busch, 1998). However, given the pervasiveness of state and local school improvement initiatives with similar requirements, it is possible that some TAP schools also engage in similar comprehensive improvement processes.

Notably, however, SWPs are allowed to commingle Title I and other federal, state, and local funds into a single pot to pay for services. In contrast, TAP schools may only leverage multiple funds through the coordination of Title I and the other sources, which require separate tracking and reporting of (1) funding by program and (2) spending by students eligible for each source (see the box “Combining of Funds” in Exhibit 1). Despite this provision, previous research has found that many SWPs do not use this flexibility, with key reasons being conflicts with state or district policy that require separate accounting for federal program funds, fear of not obtaining a clean audit, insufficient training and understanding of program and finance issues, and lack of information on how to consolidate funds (U.S. Department of Education, 2009). Aside from relatively low numbers of SWPs using their funding flexibility, previous research has not examined the relationship between the flexibility in using funds and the educational and resource allocation decisions that translate these funds into services and practices that benefit students.

Exhibit

1. Conceptual Framework for Study of

Title I Schoolwide and

Targeted Assistance Programs

In summary, this study’s collection of data from multiple sources regarding how schools use schoolwide flexibility to address the needs of low-achieving students will be used to answer the three research questions listed earlier. In addition to the three overarching study questions, more specific subquestions are associated with each. Exhibit 2 includes the study questions, as well as the study components intended to address each.

Exhibit 2. Detailed Study Questions

|

Study Components |

||

Extant Data |

Interviews |

Surveys |

|

1. How do SWPs and TAPs use Title I funds to improve student achievement, particularly for low-achieving subgroups? |

|||

a) What educational interventions and services are supported with Title I funds at the school level? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

b) How do interventions in SWPs compare with those implemented in TAPs? To what extent do SWPs use Title I funds differently from TAPs? Do they use resources in ways that would not be possible in a TAP? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

c) How do SWPs and TAPs ensure that interventions and services are helping to meet the educational needs of low-achieving subgroups? |

|

ü |

ü |

2. How do districts and schools make decisions about how to use Title I funds in SWPs and TAPs? |

|||

a) Who is involved in making these decisions? How much autonomy or influence do schools have in making decisions about how to use the school’s Title I allocation? |

|

ü |

ü |

b) Do schools and districts use student achievement data when making decisions about how to use the funds, and if so, how? |

|

ü |

ü |

c) Are resource allocation decisions made prior to the start of the school year, or are spending decisions made throughout the school year? To what extent is the use of funds determined by commitments made in previous years? |

|

ü |

ü |

3. To what extent do SWPs commingle Title I funds with other funds or coordinate the use of Title I funds with other funds? |

|||

a) To what extent do schools use the schoolwide flexibility to use resources in ways that would not be permissible in a TAP? Do they use resources in more comprehensive or innovative ways? To what extent are Title I or combined schoolwide funds used to provide services for specific students versus programs or improvement efforts that are schoolwide in nature? |

|

ü |

ü |

b) What do schools and districts perceive to be the advantages and disadvantages of commingling funds versus coordinating funds? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

c) What barriers did they experience in trying to coordinate the funds from different sources? Were they able to overcome those challenges and how? |

|

ü |

ü |

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Description of Statistical Methods

1. Sampling Design

This study will include the following two samples, which will provide different types of data for addressing the study’s research questions.

Case study sample. A set of 35 Title I participating schools in five selected states, which will be the focus of extant data collection as well as interviews with district and school officials.

Nationally representative survey sample. A sample of approximately 430 Title I district coordinators and 1,500 principals of Title I schools, in both SWP and TAP schools, will be selected and asked to complete a survey about the implementation, administration, and challenges of the schoolwide and targeted assistance programs in their schools. The district survey will also include a request for districts to upload a file listing Title I funding allocations to each of the district’s schools.

Case Study Sample

The primary sampling frame for the case studies are Title I SWP and TAP schools. To generate the sample, the study team proposes to generate a purposive sample of 35 schools nested within five selected states (California, Georgia, Michigan, New York, and Virginia) with the aim of yielding informative and varied data on a range of approaches regarding the use of Title I funds and potentially promising practices. At the state level, we sought variation on the following variables:

ESEA flexibility status, to ensure inclusion of at least one state without an approved ESEA flexibility request

Geographic region, to ensure a diverse set of states in different regions of the country.

In addition, we selected districts with multiple Title I schools that meet the school-level sampling criteria—in part to facilitate analyses of the district role in the decision-making process and in part for practical reasons (to limit data collection costs).

Although the case study sample is not designed to be nationally representative of all Title I participating schools, we do intend for schools in the sample to vary on observable state, district, and school characteristics that might be associated with patterns of Title I resource allocation practices. Exhibit 1 summarizes the expected number of case study schools, by key school-level characteristics.

Exhibit 3. Number of Case Study Sites, by Key School-Level Characteristics

Type of Title I program |

25 SWP 10 TAP |

School level |

17 elementary schools 9 middle schools 9 high schools |

Urbanicity |

7 rural schools (including 5 SWP and 2 TAP) 28 nonrural schools |

% eligible for free or reduced-price lunch |

14 schools 75-100% FRPL 13 schools 50-74% FRPL 8 schools 40-49% FRPL[1] |

School accountability status |

11 “recognition” schools[2] 12 priority or focus schools[3] 12 schools that are neither “recognition” nor priority/focus schools[4] |

AIR used a two-step sampling approach to identify prospective schools. The study team first selected the five states from which the 35 case study schools will be identified. In selecting these states, we sought variation in the key state-level dimensions. In addition, states were required to have (1) at least 28 SWP and 12 TAP schools that met the school-level criteria and (2) at least 15 SWP and 15 TAP schools that met the schooling-level criteria and are clustered within districts with schools of the same school level and other type of Title I program (e.g., Title I SWP elementary school with Title I TAP elementary school). We then selected the final sample of case study schools from the five selected states using an iterative process aimed at balancing school level, urbanicity, school accountability status, school size, and student demographics, while limiting (for cost reasons) the total number of districts represented in the sample.

Exhibit 2 provides a summary of the total numbers of school case study sites.

Exhibit 4. Number of School Case Study Sites

Total schools |

35 |

Total districts |

21 |

Total states |

5 |

Schools per state |

7 |

Schools per district |

Nationally Representative Survey Sample

The study aimed to obtain responses from about 400 districts for the district survey and 1,200 schools for the school survey. To achieve this, a sample design was implemented involving a stratified two-stage sample supporting recruitment of districts and schools, respectively. In the first stage, AIR will recruit districts from the sample into the study, and we expect that 94 percent of sampled districts will participate (for a 94 percent district response rate). The second stage will consist of recruiting sampled schools within participating districts. We expect the conditional school response rate will be 85% (i.e., 85% of sampled schools within participating districts will participate in the study), and the unweighted unconditional school response rate will be (94% * 85%) = 80%. (i.e., 80% of sampled schools in all participating and non-participating sample districts will participate in this study). The targeted response rates and survey completes imply that in order to the goal of obtaining responses from approximately 1,200 schools in 400 districts, the district sample should include about 430 districts, and the school sample should include about 1,500 schools.

The study population includes the two types of schools that are eligible for funding under the Title I program; TAP schools that tend to be lower need and are provided less flexibility in how their Title I funding can be used versus SWP that are given greater flexibility in the use of their Title I funds. The input data file used for the study frame was the 2013–14 Common Core of Data (CCD) Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey, which provides a complete listing of all public elementary and secondary schools in the United States and includes a rich set of variables on school characteristics. However, because a school’s Title I status may change from one year to another, the more recent Title I status data from EDFacts 2014–15 was used to identify the target population. Schools with no student enrollment were dropped from the study frame, as well as the following types of schools: school type other than regular or vocational, online/virtual schools, detention/treatment centers, or homebound schools. Among the 53,843 schools that remain in the study frame, 41,861 (78 percent) are SWP schools, and 11,982 (22 percent) are TAP schools. The 53,843 schools are located in 14,824 districts.

Sample Design

The study design includes data collection from a representative sample of district Title I coordinators and school principals. Therefore, representative samples of districts and schools need to be drawn from the study frame. The school sample from sampled districts should have sufficient power to detect a difference of about 10 percentage points between SWP and TAP schools, for a dichotomous item, at a significance level of 0.05 and 80 percent power. The district sample may estimate proportions with a standard error of about 3 percentage points and may produce better precision.

The study team opted to use a hybrid Systematic Sampling approach (SS) and Random Split Zone approach (RSZ) which enabled us to yield benefits of each. The SS approach is a common practice in Department of Education surveys such as the School Survey on Crime and Safety and the Schools and Staffing Survey. However, response rates have been declining in surveys in recent decades (Atrostic et al. 2001; Brick and Williams 2013; de Leeuw and de Heer 2002; Sturgis, Smith, and Hughes, 2006), and maintaining adequate response rates for districts and schools can be difficult. To this end, Random Split Zone (RSZ; Singh and Ye, 2016) was incorporated as a sampling approach for schools in this study primarily because the method provides greater flexibility than traditional sampling methods in cases where response rates are lower than expected. The RSZ design is based on a new application of the well-known and popular method of Random Groups (Rao, Hartley and Cochran, 1962; Cochran, 1977, pp. 266) to a simplified technique for drawing an approximate probability proportional to size (PPS) sample. It provides a random replacement strategy for ensuring unbiased estimation, and is based on the idea of reserve samples of size one. Using the RSZ method, the initial sample released has the same size as the target completes. Random replicates for each sampled unit are selected among similar units belonging to the same group. Thus, each case in the resulting sample of completes belongs to a different group and guarantees the representativeness of the sample. Forming groups at random as in the RSZ method helps to obtain simple unbiased variance estimates.

The primary difference between RSZ and SS is how to organize the list and pick the unit at within a stratum. For example, for a sorted list of 100 units in a stratum, SS picks the unit by an interval determined by the sample size (e.g., if 4 units need to be drawn from the population of 100 units, the first case will be selecting using a random starting value that ranges from 1 to 25; the remaining 3 cases will be selected by incrementing the preceding value by 25). Under this approach, some units will never have a chance to be sampled together, for example, units 25 and 26. This causes an important technical limitation in the approach where the estimated variance can only be approximated, rather than derived using an exact formula. In contrast to SS, for the same sorted list of 100 units, RSZ would further divide the stratum into two zones of 50 units to improve sampling efficiency. Within each zone of 50 units, RSZ would then randomly divide the units into two groups, and randomly selects a unit from each. Because samples of size one are selected in each group, RSZ will enable us to easily draw alternates as necessary. Moreover, under RSZ the variance estimate is easily computable through an exact formula, as opposed to SS which requires an approximation.

For this study, zones were defined by dividing the sorted frame list based on implicit stratification variables district urbanicity, concentration of non-Hispanic white students, district enrollment size, and ZIP code, and each zone was randomly split into groups into two groups with one sample unit being selected in each group (one case is selected as the initial sample case with others randomly selected as the replicate units). Individual random replicate units are released only when the originally sampled unit is determined to be nonresponsive. Therefore, the release of replicates can be managed individually for each ineligible or nonresponding unit instead of releasing the overall inflated sample.

The main advantages of RSZ include 1) the resulting sample of completes is representative as was planned in the original sample design; 2) it provides flexibility in the case of an unexpected low response rate; 3) it provides cost saving in the case of unexpected high response rate for a target number of completes; 4) it helps to obtain simple unbiased variance estimates. In turn, the study team used the RSZ method for the district sample and a hybrid of RSZ and traditional sampling method for the school sample; we will release an initial sample of 1,412 schools in the responding 400 districts with no intention to release any replacement schools, although the schools were drawn using the RSZ procedure and replacement schools are available. Twenty-seven very large districts (with student enrollment greater than 100,000) were selected with certainty to guarantee their representation in the study. These certainty districts do not have replacement districts. If any of these do not respond, there will be a loss in the final sample size because no replacements are available for certainty districts. There are also possibilities that a respondent cannot be obtained for a group within the data collection after multiple releases. Based on these practical considerations and random numbers of schools available for a given set of districts, the number of districts and schools that were selected into the initial sample were increased to 404 and 1,421 schools to counter potential sample losses. In all, we expect to release about 430 districts in total with about 26 districts released as replacements.

The sampling consisted of two stages. The first stage of selection was be to sample districts, which the second stage was to sample schools within those districts selected in the first stage. Because the study intends to make comparisons between SWP and TAP schools, comparable sample sizes are desired for the SWP school group and TAP school group, which means a higher sampling rate is needed for the TAP group due to the lower proportion of TAP schools in the study frame. The study will also make comparisons across school poverty levels measured by percentage of free or reduced-price lunch eligible students. To this end, the information about program type and school poverty level was used to stratify the frame to control for sample sizes in subgroups and improve efficiency of the sample. However, districts can have both SWP schools and TAP schools and schools at different poverty levels. Therefore, districts had to be classified according to both program type and poverty level3, among all of the schools within the district. To assist in the control of sample sizes by school program type and poverty level, two district-level variables were created. The first variable for district program type had three categories: a district with SWP schools only, a district with TAP schools only, and a district with both types of schools. The second variable for district poverty levels used the overall percentage of free or reduced-price lunch eligible students in the district and the districts were classified into three categories: percentage of free or reduced-price lunch eligible students less than 35 percent, 35 percent to 74 percent, and 75 percent or higher. A stratification variable was created using these two variables (district program types and district poverty level), and as shown in Exhibit 3, yielded three times three or nine stratification cells. Because the populations are highly disproportionate over program type and poverty, it was necessary to sample the different subpopulations with different rates in order to achieve more balanced sample sizes in subgroups. We sampled the smaller subpopulations (districts with only TAP schools and those with both SWP and TAP schools) at higher rates are shown in Exhibit 3. The overall sampling rates were 2 percent for districts with SWP schools only, 4 percent for districts with TAP schools only, and 6 percent for districts with both types of schools. The overall sampling rate was 4 percent for districts at low poverty level (lower than 35% of enrollment eligible for FRPL), 2 percent for districts at medium poverty level (not lower than 35% and lower than 75% of enrollment eligible for FRPL), and 4 percent for districts at high poverty level (not lower than 75% of enrollment eligible for FRPL).

Exhibit 5. Number and percent of districts in the study frame, allocated sample size, and sampling rate by stratum

Stratum |

District Program Type |

District Poverty Level |

Study Frame |

|

Sample |

|

Sampling Rate |

|||

Count |

Percent |

|

Count |

Percent |

|

|||||

Total |

|

|

14,824 |

100% |

|

404 |

100% |

|

3% |

|

11 |

SWP Only |

Pov < 35% |

510 |

3% |

|

10 |

2% |

|

2% |

|

12 |

SWP Only |

35% ≤ Pov < 75% |

5,572 |

38% |

|

56 |

14% |

|

1% |

|

13 |

SWP Only |

75% ≤ Pov < 100% |

2,253 |

15% |

|

68 |

17% |

|

3% |

|

21 |

TAP Only |

Pov < 35% |

3,081 |

21% |

|

123 |

30% |

|

4% |

|

22 |

TAP Only |

35% ≤ Pov < 75% |

2,105 |

14% |

|

63 |

16% |

|

3% |

|

23 |

TAP Only |

75% ≤ Pov < 100% |

252 |

2% |

|

25 |

6% |

|

10% |

|

31 |

SWP and TAP |

Pov < 35% |

271 |

2% |

|

14 |

3% |

|

5% |

|

32 |

SWP and TAP |

35% ≤ Pov < 75% |

665 |

4% |

|

33 |

8% |

|

5% |

|

33 |

SWP and TAP |

75% ≤ Pov < 100% |

115 |

1% |

|

12 |

3% |

|

10% |

|

NOTE: Detail may not sum to total due to rounding.

In sampling the districts, the method of RSZ was used as follows. The district list was sorted by district urbanicity, concentration of non-Hispanic white students, district enrollment size, and ZIP code (so districts were geographically ordered). Roughly equal-size zones were defined along the sorted list so that within each zone the district characteristics were similar. Roughly equal-size random groups were defined within each zone and one district was selected from each group, which means the number of groups was equal to district sample size (i.e., 404 groups were created). Each zone included two groups which is the minimum requirements for variance estimation without collapsing the zones. A few zones had three groups because sometimes the district sample size within a stratum was an odd number. For example, if the total sample size for a certain stratum was 11, then 11 roughly equal groups needed to be created within the stratum, which led to five zones defined in the stratum with four of them randomly split into two groups, and one of them split into three groups. Within each group, one district was randomly selected with probability proportional to size (PPS). The measure of size (MOS) was the average number of SWP schools and TAP schools within each district. Sequentially, replacement districts were selected and labeled in each group in case the original district in the group does not participate for any reason and needs to be replaced to meet the targets.

After the district selection, schools in the sampled districts were stratified by school program type. Again, the method of RSZ was used as follows. The school list were sorted by school level, urbanicity, concentration of free or reduced-price lunch eligible students, concentration of non-Hispanic white students, enrollment size, and ZIP code. Roughly equal-size zones were defined along the sorted list so that within each zone the school characteristics are similar, and the zones were randomly split into groups. Within each group, one school was randomly selected. Replacement schools were available although there is no intention to use them. The number of schools of each type to be selected in each sampled district was up to four in non-certainty districts and up to 12 (5 percent) of the schools in certainty districts.4 The current sample design allows for replacements for nonresponding districts or schools although there is no intention to release replacement schools in this study because of the concerns about timeline.

Weighting and Variance Estimation Procedures

Weights have been created for analysis so that a weighted response sample is unbiased. The district and school weights reflect the sample design by taking into account the stratification and include adjustments for differential response rates among different subgroups. Within each group in each zone in each stratum, the district selection probabilities were calculated as follows:

where

is

the assigned sample size for group i, and

is

the assigned sample size for group i, and

is

the MOS of district j in group i. The district base

weight is the reciprocal of the district selection probabilities:

is

the MOS of district j in group i. The district base

weight is the reciprocal of the district selection probabilities:

.

.

Within each district in the sample, the school selection probabilities were calculated as follows:

where

is

the sample size (up to four as discussed earlier in the memo) for

school level k in the district j in group i and

is

the sample size (up to four as discussed earlier in the memo) for

school level k in the district j in group i and

is

the number of schools in school level k in the district j

in group i. The school base weight is the district base weight

times the reciprocal of the school selection probability:

is

the number of schools in school level k in the district j

in group i. The school base weight is the district base weight

times the reciprocal of the school selection probability:

.

.

Nonresponse adjustments will be conducted at both

of the district and school levels. The nonresponse adjustment factor

( for districts and

for districts and

for schools) will be computed as the sum of the weights for all the

sampled units in a nonresponse cell divided by the sum of the weights

of the responding units in nonresponse cell c. The final district

weight is a product of the district base weight and the district

nonresponse adjustment factor:

for schools) will be computed as the sum of the weights for all the

sampled units in a nonresponse cell divided by the sum of the weights

of the responding units in nonresponse cell c. The final district

weight is a product of the district base weight and the district

nonresponse adjustment factor:

.

.

The final school weight is a product of the school base weight factor and the school nonresponse adjustment factor:

After the nonresponse adjustment, the weights will be further adjusted such that the sum of the final weights matches population totals for certain demographic characteristics.

Standard errors of the estimates will be computed using the Taylor series linearization method that will incorporate sampling weights and sample design information (e.g., stratification and clustering).

2. Procedures for Data Collection

The procedures for carrying out the case study and survey data collection activities are described in the following section.

Procedures for Extant Data Collection to Inform Case Studies

The study team will use a comprehensive request for documents (RFD) to collect extant data from districts and schools; the RFD will include the types of information needed to produce a detailed analysis of how schools use Title I and other funds. More specifically, the extant data will contribute to answering research questions 1 and 2. Related to the first research question, extant data such as school-level Title I plans will be used to identify the educational interventions and services that are supported with Title I funds at the school level, including how interventions and services differ between SWPs and TAP schools. For research question 3, school budgets and planning documents, will contribute to the analysis of the extent to which schools use schoolwide funds flexibility in ways that would not be permissible in a TAP school. The data will also be analyzed to identify any potentially innovative ways of using funds to support improvement efforts.

The RFD will request from districts and schools the following documents for the case study schools selected for this study:5

Materials describing the annual school-level budgeting/planning process

Title I SWP plans (or for TAP Schools, any school improvement plans or Title I spending plans) for the current and prior year6

Complete school-level budgets for the current and prior year

Minutes from meetings among school-level staff and parent councils where resource allocation decisions were made for the current and prior year

Chart of accounts that identifies fund codes that identify planned expenditures to be covered by Title I and other funds, and will help determine if schools combine or commingle funds.

Other written planning documentation, budget narratives, or funding applications they can share

RFDs will be sent to district staff and to school principals in an e-mail only after the school has agreed to participate. To place minimal burden on those providing the data, the study team will not ask providers to modify the information they provide, but to send extant materials in the format most convenient for them. The RFD also will include instructions for providing this information through a variety of acceptable methods (FTP, e-mail, or postal mail). After sending the RFD and prior to collecting any extant data from the school or district, the research team will follow up in an e-mail to schedule a brief 10–15 minute follow-up call with the data provider. The purpose of the call will be for the study team to answer any clarifying questions so as to ensure providers do not spend unnecessary time preparing files or collecting data that are not needed for the study. The administration of the RFD will mark the beginning of the data collection effort and is expected to start in fall 2016.

Procedures for Case Study Site Visit and Interview Data Collection

To answer questions on the use of Title I (and other) funds to implement school improvement interventions, the study team will conduct site visits to 35 case-study schools in five states. In each school site, research staff will conduct interviews with principals and up to three additional respondents—including an assistant principal with responsibility for school budgeting, a teacher paid through Title I, and a group interview with a school improvement team involved with resource allocation decisions. We recognize that smaller schools may not have an individual (other than the principal) who is responsible for the school budget, so in these schools those questions will be asked of the principal. Moreover, TAP schools may not have sufficient funds to pay the salary of a staff member, so in these schools, we may not interview teachers funded through Title I. (Exhibit 1 in Part A reflects these assumptions.) In addition to interviews with school-level staff, the study team will interview two district administrators with primary responsibility for Title I schools, funding decisions, and school improvement processes. As necessary, the study team will conduct follow-up telephone interviews for the purpose of obtaining key missing pieces of information, but we will seek to limit this practice.

Training for site visitors. Prior to the first wave of data collection, all site visit staff will convene in Washington, D.C., for a one‑day training session. The site visit team leads will jointly develop and conduct the training. The purpose of the training is to ensure common understanding of the site visit procedures, including the following: pre-visit activities such as reviewing extant data for the site, tailoring protocols, scheduling the visit, and communicating with site contacts; procedures to be followed during visits; and post-visit procedures such as following up with respondents to obtain greater clarification on a topic that was discussed or to collect additional materials or information that were identified during the visit as important for the study. This day-long training for the case study team also will focus on ensuring a shared understanding of the purpose of the study, the content of the protocols, and interview procedures. In terms of interview procedures, the training will include discussions and role-playing to learn strategies for avoiding leading questions, promoting consistency in data collection, and conducting interviews that are both conversational and systematic.

Prior to the training, the site visit task leaders will develop a site visit checklist that outlines all tasks the site visitors need to perform before, during, and after each visit. All site visit team members will adhere to this checklist to ensure that visits are conducted efficiently, professionally, and consistently.

Scheduling site visits and interviews. To ensure the highest quality data collection, the site visit team will consist of two researchers with two complementary areas of expertise: one with expertise in Title I implementation and school improvement and the second with expertise in resource allocation and school budgets. Each site visit team will be responsible for scheduling the visits and interviews for their assigned sites. For each site, the teams will work with district and school staff to identify appropriate respondents prior to the site visit and develop a site visit and interview schedule. Because of the anticipated variation in district and school enrollment (among other variables), the job titles and roles of interviewees will vary across sites. At present, we anticipate two district interviewees and three school-level interviewees per site.

We anticipate that, for each study site, the district interviews and one school visit can be completed in a single day. Additional days may be required in some district sites, depending on the number of schools sampled within a single district. For example, in the case of a district with two sampled schools, we envision the schedule shown in Exhibit 6.

Exhibit 6. Sample Interview Schedule

DAY 1 |

|

District interviews |

|

Superintendent interview |

9–10 a.m. |

Additional district official interview |

10:30–11:30 a.m. |

Travel to school site |

|

School 1 |

|

Principal interview |

12–1 p.m. |

Assistant principal interview |

1–2 p.m. |

School improvement team group interview |

2–3 p.m. |

Meet with administrative assistant to confirm receipt of extant data (as necessary) |

3–3:30 p.m. |

Return to hotel, clean interview notes |

3:30–5:30 p.m. |

Exhibit 6. Sample Interview Schedule, continued

DAY 2 |

|

School 2 |

|

Principal interview |

8:30–9:30 a.m. |

Budget director interview |

9:30–10:30 a.m. |

Title I teacher interview |

10:30–11:15 a.m. |

School improvement team group interview |

11:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. |

Meet with administrative assistant to confirm receipt of extant data (as necessary) |

12:30 – 1:00 p.m. |

Return travel |

|

Conducting interviews. In preparation for each visit and to facilitate and streamline the interviews with respondents, site visit teams will consider the reasons each jurisdiction was selected for inclusion in the purposive sample and review any relevant information from state education agency websites (such as Title I guidance or presentation documents) as well as other extant data collected on each site. The teams will then annotate each section of the individual interview protocols accordingly. These annotated notes will be used to tailor the wording of each question, as appropriate. The use of experienced interviewers, coupled with careful preparation, will ensure that interviews are not “canned” or overly formal. When possible, both members of each site visit team will attend all interviews if possible. In some instances, site visitors may conduct interviews separately if this is absolutely necessary to collect information from all respondents. In addition, each interview will be audio recorded with permission from the respondent(s).

Data management. In preparation for the site visits and while on site, the study team will use Microsoft OneNote to organize extant data, interview protocols, and audio files. Prior to each visit, the site visit team will enter extant data into OneNote for reference in the field. With respondent permission, all interviews will be audio-recorded through OneNote, which allows typed text to be linked with audio data. This feature of OneNote facilitates transcription as well as easy retrieval of audio data. During each interview, one team member will be conducting the interview and one will take simultaneous notes. We will seek to structure the day such that there is time to review and supplement interview notes while in the field that can help streamline and focus subsequent interviews with district and school staff based on the information that has been gathered.

Quality control. The case study site visit and interview data collection process will make use of the following quality control procedures: (1) weekly site visit debriefings among the team to identify logistical and data collection concerns; (2) a formal tracking system to ensure that we are collecting the required data from each site; and (3) adherence to the timely cleaning and posting of interview notes and written observations, as well as interview audio transcripts, to a secure project website for task leaders to check for completeness and consistency.

Survey Data Collection: Preparation

Nationally representative, quantitative survey data will be collected from district Title I coordinators and principals in Title I SWP and TAP schools. These data will complement the results of the case studies and extant data analyses by providing a higher level, national picture of Title I program implementation.

Target Population. The sample selection for the surveys was completed in June 2016, subject to OMB approval. The survey sample was drawn from the 2013–14 CCD Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey, which provided a complete listing of all public elementary and secondary schools in the United States. The goal is to achieve an 85 percent response rate or 1,200 completed questionnaires from principals and a 92 percent response rate or 400 responses from district coordinators.

Sample Preparation. A list of sampled districts from the 2013–14 CCD file was generated as part of the sampling process. The CCD file contains the addresses and phone numbers for districts, but not the names, titles, or e-mail addresses of key contacts in the district. As such, although the CCD data provide a starting point for creating a database of contact information for each of the sampled districts, the information is not adequate for administering the study’s survey. To gather data on Title I programming activities, the study team needs to ensure that the survey is directed to the Title I coordinator in the district (or other identified official who holds responsibility for Title I programming in the district). Therefore, in addition to the CCD data, the study team will engage in Internet searches and, as needed, phone calls to each of the districts’ central office to identify the official who is in the best position to respond to the survey, verify this person’s contact phone number and e-mail address, and to determine whether the information in the CCD file is correct.

The study team also will investigate whether any of the districts require advance review and approval of surveys being conducted in their districts. For those districts requiring advance review and approval, a tailored application will be developed and submitted; typically, the application will include a cover letter, research application or standard proposal for research, and copies of the questionnaires.

As with the list of sampled districts, a list of schools was generated from the 2013–14 CCD file during sampling. The study team will again use Internet searches and phone calls to verify the CCD data on school contact information is accurate before the survey begins and to obtain the names and e-mail addresses of the schools’ principals.

Building Awareness and Encouraging Participation. Survey response rates are improved if studies use advance letters from the sponsor of the study or other entities that support the survey (Lavrakas, 2008). Therefore, the study team will prepare a draft letter of endorsement for the study from ED that will include official seal and will be signed by a designated ED official. The letter will introduce the study to the sample members, verify ED’s support of the study, and encourage participation. The study team will submit the draft letter as part of the OMB package and will customize as needed prior to contacting each of the respondents.

We will also encourage districts to show support for the principal survey to increase response rates. Some districts may prefer to send an e-mail directly to the sampled principals, post an announcement on an internal website, or allow the study team to attach an endorsement letter from the superintendent or other district official to the data collection materials. To promote effective endorsements and minimize the burden on districts, the research team will work with the districts to draft materials that support the study and provide an accurate overview of the study, its purposes, the benefits of participating, and the activities that are associated with participation.

Following OMB approval, advance notification and endorsement letters (letters of support from the U.S. Department of Education, superintendents, and district officials as appropriate) alerting sampled district coordinators and principals to the study and encouraging their participation will be sent starting on September 22, 2016. We expect the survey launch will occur on September 26, 2016. All data collection activities will conclude 16 weeks later on January 6, 2017.

Survey Administration Procedures

District coordinators and school principals will be offered varied and sequenced modes of administration because research shows that the using a mixed-mode approach increases survey response rates significantly (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014). Different modes will be offered sequentially rather than simultaneously because people are more responsive to surveys when they are offered one mode at a time (Miller & Dillman, 2011).

Both district coordinators and principals will be offered the option to complete the survey online. We expect that both respondent groups have consistent access to the Internet and are accustomed to reporting data electronically. For district administrators who do not respond to electronic solicitations, we will make reminder telephone calls encouraging online completion. If a district requests a hard-copy survey when contacted by telephone, AIR will send the survey via U.S. mail. For nonrespondent school principals, the study team will provide the opportunity to complete the questionnaire on paper if they prefer that mode to the online platform. This design is the most cost-effective way of achieving the greatest response rates from both groups.

Web Platform and Survey Access. The contractor currently uses the DatStat Illume software package to program and administer surveys and to track and manage respondents. Illume can accommodate complex survey formatting procedures and is appropriate for the number of cases included in this study. Respondents will be able to access the survey landing page using a specified website and will enter their assigned unique user ID to access the survey questions. This unique user ID will be assigned to respondents and provided along with the survey link in their survey invitation letter as well as reminder e-mails. As a respondent completes the questionnaire online, their data are saved in real time. This feature minimizes the burden on respondents so that they do not have to complete the full survey in one sitting or need to worry about resubmitting responses to previously answered questions should a session time out or Internet access break off suddenly. In the event that a respondent breaks off, the data they have provided up to that point will be captured in the survey dataset and Illume allows them to pick up where they left off when they return to complete the questionnaire.

Paper Questionnaires. In an effort to minimize costs and take advantage of the data quality benefits of using Web surveys (Couper, 2000), the survey will start with a Web-only approach. However, in an attempt to encourage response among sampled principals who may prefer to complete the survey by mail, paper questionnaires will be sent to those who do not initially complete the survey online.

Nonresponse Follow-Up. The study team will follow-up with non-responding schools and districts at 2-week intervals. Schools will receive up to two email reminders, then (if needed) a paper version of the questionnaire via postal mail, and then a third email reminder. Districts will receive three email reminders, followed by telephone follow-up calls if needed. Well-trained telephone interviewers will call the district Title I coordinator who was identified in advance as the key contact. Paper questionnaires will be provided for the interviewers to use if the respondent indicates that he or she is willing to complete the questionnaire over the phone.

Replacement Districts. Replacement districts will be used in the following circumstances, providing sufficient time is available to carry out the data collection procedures:

District denies research application and PPPS is unable to convert the district’s decision

Decision date on the submitted research application is outside the data collection window and PPPS is unable to get approval

District is no longer active

District respondent does not respond to survey

District respondent refuses to respond to survey

Exhibit 7 shows the timeline for data collection.

Exhibit 7. Data Collection Timeline

Event |

Population |

|

Districts |

Schools |

|

Select sample |

6/1/16–6/30/16 |

6/1/16–6/30/16 |

Sample preparation |

6/1/16–7/31/16 |

6/1/16–7/31/16 |

Materials and survey instrument preparation |

8/1/16 - 9/21/16 |

8/1/16 – 9/21-16 |

Mail advance letter and endorsements |

9/22/16 |

9/27/16 |

Mail/e-mail web invitation sent |

9/26/16 |

9/29/16 |

First reminder e-mail sent |

10/13/16 |

10/13/16 |

Second reminder e-mail sent |

10/27/16 |

10/27/16 |

Paper questionnaires mailed |

N/A |

11/7/16 |

Third reminder e-mail sent |

11/10/16 |

11/30/16 |

Telephone nonresponse follow-up |

11/28/16–1/6/17 |

N/A |

Help desk. The contractor will staff a toll-free telephone and e-mail help desk to assist respondents who are having any difficulties with the survey tool. These well-trained staff members will be able to provide technical support as well as answer more substantive questions such as whether the survey is voluntary and how the information collected will be reported. The help desk will be staffed during regular business hours and inquiries will be responded to within one business day.

Monitoring data collection. The contractor will monitor online responses in real time and completed paper questionnaire will be entered into a case management database as they are received. This tracking of online and paper completions in the case management database will provide an overall, daily status of the project’s data collection efforts. We will identify those district and school administrators who have not yet responded and decide whether additional nonresponse follow-up is needed outside of those interventions outlined above. For example, if previous attempts are unsuccessful, we will try other means of verifying that we have correct contact information, make additional follow-up telephone calls, or re-mail the paper questionnaire.

3. Methods to Maximize Response Rate

Data collection is a complex process that requires careful planning. The team has developed interview protocols and survey instruments that are appropriately tailored to the respondent group and are designed to place as little burden on respondents as possible. The team has used cognitive interviews with principals and district coordinators to pilot survey data collection instruments to ensure that they are user‑friendly and easily understandable, all of which increases participants’ willingness to participate in the data collection activities and thus increases response rates.

Recruitment materials will include ED and the school district’s endorsement of the study. The materials will emphasize the social incentive to respondents by stressing the importance of the data collection to provide much‑needed technical assistance and practical information to districts and schools. In addition to carefully wording the recruitment materials, district coordinators and principals will be offered varied and sequenced options for completing and submitting the survey because using a mixed-mode approach increases survey response rates. Both district coordinators and principals will first be offered the option to complete the survey online. For district coordinators who do not respond online after three e-mail reminders, reminder telephone calls will be made. Principals who do not respond online will be sent a paper version of the questionnaire to complete and return by U.S. mail.

4. Expert Review and Piloting Procedures

To ensure the quality of the data collection instruments, the study team conducted an initial set of informational interviews, will pilot test the draft instruments, and will convene a Technical Working Group (TWG). As the first step in this instrument development process, the study team engaged in a series of informational interviews with current and former Title I school staff, respecting the limits regarding the number of respondents allowable prior to OMB clearance (no more than nine). These informational interviews helped inform the organization and content of the interview questions and to ensure the study team has drafted items that will result in high-quality data to address the study’s research questions.

These informational interviews did not replace piloting procedures, which comprise the second phase of the instrument development process. The study team will conduct cognitive interviews with a limited set of principals and district officials to pilot the survey items, again respecting limits regarding the number of respondents prior to OMB clearance. The study team anticipates that the cognitive interviews will be particularly helpful in revising survey items related to the allocation of Title I funds and decision-making about use of Title I resources.

5. Individuals and Organizations Involved in Project

AIR is the contractor for the Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs. The project director is Dr. Kerstin Carlson Le Floch, who is supported by an experienced team of researchers leading the major tasks of the project. Contact information for the individuals and organizations involved in the project is presented in Exhibit 8.

Exhibit 8. Organizations, Individuals Involved in Project

Responsibility |

Contact Name |

Organization |

Telephone Number |

Project Director |

Dr. Kerstin Carlson Le Floch |

AIR |

(202) 403-5649 |

Deputy Project Director |

Dr. Jesse Levin |

AIR |

(650) 843-8270 |

Special Advisor |

Dr. Beatrice Birman |

AIR |

(202) 403-5318 |

Special Advisor |

Dr. Jay Chambers |

AIR |

(650) 843-8111 |

Special Advisor |

Dr. Sandy Eyster |

AIR |

(202) 403-6149 |

Extant Data Task Lead |

Karen Manship |

AIR |

(650) 843-8198 |

Interview Task Lead |

Dr. Courtney Tanenbaum |

AIR |

(202) 403-5304 |

Survey Task Lead |

Kathy Sonnenfeld |

AIR |

(609) 403-6444 |

Consultant |

Dr. Bruce Baker |

Graduate School of Education at Rutgers University |

(848) 932-0698 |

Consultant |

Dr. Margaret Goertz |

CPRE at the University of Pennsylvania |

(215) 573-0700 |

Consultant |

Dr. Diane Massell |

Massell Education Consulting |

(734) 214-9591 |

References

Brick, J.M. and Williams, D. (2013). Explaining rising nonresponse rates in crosssectional surveys. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 645, 36-59.

Cochran, W.G. (1977). Sampling Techniques. 3rd Ed., New York: John Wiley

Couper, M. P. (2000). Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(4), 464–494.

De Leeuw, E. and de Heer, W. (2002). Trends in household survey nonresponse: A longitudinal and international comparison. In: Groves, R.M., Dillman, D.A., Entinge, J.L., and Little, R.J.A. (eds.). Survey nonresponse. NY: John Wiley and Sons: 41-54.

Dillman, D., Smyth, J., & Christian, J. (2014). Internet, phone, mail and mixed-mode surveys (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kish, L. (1965). Survey sampling. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lavrakas, Paul J., ed., (2008). Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Lohr, S.L. and Brick, J.M. (2014). Allocation for dual frame telephone surveys with nonresponse. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 2, 388-409.

Miller, M. M. & Dillman, D. A. (2011). Improving response to Web and mixed-mode surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(2), 249–269.

Rao, J. N. K., Hartley, H. O., and Cochran, W. G. (1962). On a simple procedure of unequal probability sampling without replacement. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 24, 482-491.

Singh, A.C., and Ye, C. (2016). Randomly split zones for samples of size one as reserve replicates and random replacements for nonrespondents. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Section on Survey Research Methods (to be presented in Chicago, IL).

Sturgis, P., Smith, P., and Hughes, G. (2006). A study of suitable methods for raising response rates in school surveys. Nottingham, England: DfES Publications.

1 Source: 2014–15 EDFacts, Data Group (DG) 22: Title I Status.

2 Details on the components and rules governing the use of funds for SWP versus TAP schools can be found in sections 1114 and 1115 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Title I, Part A.

[1][1] The case study sample includes only schools with 40 percent or more students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches because that is the eligibility threshold for schoolwide programs.

[2][2] “Recognition” schools are defined as (1) “reward” schools in states with an approved ESEA waiver; AND/OR (2) schools in the highest state-defined level of school status in states using a state-designated accountability system.

[3][3] Schools in this category may also include those in corrective action or restructuring for states without an approved ESEA waiver.

[4][4] Schools in this category may also include those not identified for improvement for states without an approved ESEA waiver.

3 Poverty level is used to classify districts because it is relevant to how the school can use Title I funds.

4 If the non-certainty district has no more than four SWP schools, all schools were selected; if it has more than four SWP schools, four were selected. The same principle applies for TAP schools. More schools were sampled in the certainty districts to include a more representative sample of schools for these self-representing districts.

5 We note that some documentation may be held centrally by district offices rather than at the schools themselves.

6 School-level plans, budgets, meeting minutes and student enrollment will be requested for each sampled school for the current and prior year, so that we may better understand changes in spending over time and those decisions that led to differences in resource allocation, as well as to limit the risk of year-specific anomalies distorting the analysis findings.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Information Technology Group |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-23 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy