Material for Testing - 9

PrEP#12(FAQs)v2.4_to CDC.DOCX

Generic Clearance for the Collection of Qualitative Feedback on Agency Service Delivery (NCHHSTP)

Material for Testing - 9

OMB: 0920-1027

MS v2.3 4.5.16

MS v2.3 4.5.16

CDC PrEP/PEP Provider materials:

(Front, page 1)

(Branding element PrEP portion of the logo)

(headline)

PrEP Provider FAQs

(text)

1. What is PrEP?

PrEP is short for pre-exposure prophylaxis. It is the use of antiretroviral medication to prevent acquisition of HIV infection. PrEP is used by HIV uninfected people who are at high risk of being exposed to HIV through sexual contact or injection drug use. At present, the only medication with an FDA-approved indication for PrEP is oral tenofovir emtricitabine (TDF-FTC), which is available as a fixed-dose combination in a tablet called Truvada®. This medication is also commonly used in the treatment of HIV.

PrEP should be considered part of a comprehensive prevention plan that includes a discussion about adherence, safer sex behaviors, and condom use.

2. What are the guidelines for prescribing PrEP?

Comprehensive guidelines for prescribing PrEP exist:

• Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Guidelines,[1] including a Clinical Providers’ Supplement [2]

Both can be found on the CDC website: www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep

The Clinical Providers’ Supplement contains additional tools for clinicians providing PrEP, such as a patient/provider checklist, patient information sheets, provider information sheets, a risk incidence assessment, supplemental counseling information, billing codes, and practice quality measures.

If questions arise or if prescribing assistance is needed, clinicians should consult the National Clinicians Consultation Center PrEP Line @ 1-855-448-7737 (11 AM till 6 PM EST).

3. Who can prescribe PrEP?

Any licensed prescriber can prescribe TDF-FTC as PrEP. Specialization in infectious diseases or HIV medicine is not required. In fact, primary care providers who see members of populations at high risk of HIV should consider offering PrEP to all eligible patients.[3]

4. To whom should I offer PrEP?

Per CDC Guidelines, PrEP may be appropriate for the following populations:

(table)

|

Men Who Have Sex with Men |

Heterosexual Women and Men |

Injection Drug Users |

Signs of substantial HIV risk |

• HIV-positive sexual partner • Recent bacterial STI • High number of sex partners • History of inconsistent or no condom use • Commercial sex work |

• HIV-positive sexual partner • Recent bacterial STI • High number of sex partners • History of inconsistent or no condom use • Commercial sex work • In high-prevalence area or network |

• HIV-positive injecting partners • Sharing injection equipment • Recent drug treatment (but currently injecting) |

Within these populations, people at very high risk include:

• 1 in 4 sexually active gay and bisexual adult men without HIV

• 1 in 200 sexually active heterosexual adults without HIV

• 1 in 5 adults without HIV who inject drugs

Clinicians

should also discuss PrEP with the following non-HIV-infected

individuals (other than those mentioned above):

• Male-to-female and female-to male transgender individuals engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors

• People who inject drugs and report any of the following behaviors:

• Sharing injection equipment (including to inject hormones among transgender individuals)

• Injecting one or more times per day, injecting cocaine or methamphetamine

• Engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors

• Individuals who use stimulant drugs associated with high-risk behaviors, such as methamphetamine

• Individuals who have been prescribed non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and demonstrate continued high-risk behavior or have used multiple courses of PEP

Among men who have

sex with men (MSM), high-risk behaviors can be quantified using the

HIRI-MSM risk index featured in the national guidelines.[4]

(See section 6 of the CDC Clinical Providers’ Supplement that

accompanies the national guidelines.) This includes a screen for such

behaviors as anal sex without a condom, having HIV-positive partners,

and use of crystal meth or poppers.

5. How is TDF-FTC for PrEP prescribed?

TDF-FTC for oral PrEP is taken once daily by mouth.*

PrEP should be discontinued immediately if (1) the patient becomes HIV-infected, (2) the patient experiences toxicity or symptoms that cannot be managed, or (3) the patient becomes pregnant. (Note that in some cases, PrEP may be restarted for ongoing HIV prevention during pregnancy if the risk of ongoing HIV transmission is sufficiently high [such as in a serodiscordant partnership] and because pregnancy itself is associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition, as discussed in question 7, as well.) Condoms and supportive counseling, both for adherence and risk reduction, are required.

(small text at base of page)

*Full prescribing information is available at http://www.gilead.com/pdf/truvada_pi.pdf.

6. What is the evidence base for PrEP?

Multiple studies have demonstrated that PrEP is effective: [p23 CDC Guidelines, Table 4] In all of these studies, HIV transmission risk was lowest for participants who took the pill consistently. Specifically:

Among gay and bisexual men, those who were given PrEP were 44% less likely overall to acquire HIV than those who were given a placebo. Among the men with detectable levels of drug in their blood (a measure of compliance), PrEP reduced the risk of infection by as much as 92%. (iPrEx Study)[6]

Among heterosexually active men and women, PrEP reduced the risk of getting HIV by 62%. Participants who became infected had far less drug in their blood, compared with matched participants who remained uninfected. (TDF2 Study)[8]

Among men and women in HIV discordant couples, those who received PrEP were 75% less likely to become infected than those on placebo. Among those with detectable levels of medicine in their blood, PrEP reduced the risk of HIV infection by up to 90%. (Partners PrEP Study) [7]

Among injection drug users, a once-daily tablet containing tenofovir (one of the two drugs in PrEP) reduced the risk of getting HIV by 49%. For compliant participants who had detectable tenofovir in their blood, PrEP reduced the risk of infection by 74%. (Bangkok Tenofovir Study)[11]

None of the studies found any significant safety concerns with use of daily oral PrEP. Some trial participants reported side effects, such as an upset stomach or loss of appetite, but these were mild and usually resolved in the first month.

Studies among women are discussed in questions 7 and 9.

How important is adherence to PrEP?

In all PrEP clinical trials to date, PrEP efficacy appears to be dependent upon adherence.[12,13] According to a dedicated analysis of adherence from all trials to date, PrEP was non-effıcacious when adherence was low, but when moderate or high adherence was achieved, efficacy was modest or relatively high, respectively.[13] Among the study subjects with detectable plasma tenofovir levels in iPrEx, Partners PrEP, TDF2, and BTS, efficacy ranged from 74 to 92%.[6,7,8,11,22]

Adherence to PrEP was also found to be highly associated with reduction of HIV risk in an open-label study (iPrEX OLE). [14] There were no HIV infections in participants using four or more tablets per week as detected by dried blood spot. Among participants with less drug detected, HIV incidence ranged from 4.7 infections per 100 person-years (no drug detected) to 0.6 per 100 person-years (two to three tablets per week).

7. Is PrEP safe?

Yes, in prevention studies to date, TDF-FTC for PrEP has not caused serious short-term safety concerns.[5,15,16]. TDF-FTC has caused renal toxicity and decreased bone mineral density, when used by HIV-infected people for HIV treatment, and administered for months and years.

PrEP is considered safe for women of childbearing age. Decisions about use during pregnancy must be individualized: while available data suggest that TDF-FTC does not increase risk of birth defects, there are not enough data to exclude the possibility of harm (TDF-FTC: Pregnancy Class B). PrEP is often used in pregnancy if the risk of ongoing HIV transmission is sufficiently high (such as in a serodiscordant partnership) and because pregnancy itself is associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition.

Since TDF-FTC is actively eliminated by the kidneys, it should be co-administered with care in patients taking medications that are eliminated by active tubular secretion (e.g., acyclovir, adefovir dipivoxil, cidofovir, ganciclovir, valacyclovir, valganciclovir, aminoglycosides, and high-dose or multiple NSAIDs). Drugs that decrease renal function may also increase concentrations of TDF-FTC.

8. Who is not eligible for PrEP?

1. HIV-positive people. Individuals must be confirmed as HIV-negative before initiating PrEP. Excluding those with acute HIV infection is critically important, as there is a risk of developing resistant HIV if they are inadvertently started on TDF-FTC as PrEP. (TDF-FTC is an appropriate component of a regimen to treat HIV, but must be combined with an additional agent from another class of antiretrovirals to provide effective treatment.)

2. People with renal insufficiency. Providers should confirm that the patient’s calculated creatinine clearance is ≥60 mL/minute (Cockcroft-Gault formula) before initiating PrEP.

Additionally, those who indicate that they are not ready to adhere to daily oral TDF-FTC should not be prescribed PrEP (since efficacy is extremely limited when patients do not adhere, as described above).

9. Does PrEP work in women?

Two trials of PrEP in women were stopped early for futility by their respective data safety and monitoring boards.[9,10] A determination of futility is made when it appears that no evidence of efficacy would be found in the future based on the results collected up to that point. Although one study’s results have not yet been published, low adherence among the participants was thought to be a substantial factor in the futility finding. Other studies that included both men and women (TDF-2, Partners PrEP) in whom higher levels of adherence were achieved did show efficacy among women. Therefore, current recommendations include women as candidates for PrEP.

10. What baseline assessment is required for individuals beginning PrEP?

The most important aspect of the baseline assessment is ascertaining that the patient is not already HIV-infected. HIV testing should be conducted immediately prior to starting PrEP, ideally on the same day the prescription is provided.

Baseline testing should be conducted with third-generation or fourth-generation HIV tests (for a list of FDA-approved third- and fourth-generation tests, go to http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/ laboratorytests.html.) For patients with symptoms of acute infection or for those whose antibody test is negative but who have reported unprotected sex with an HIV-infected partner in the past month, a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT, viral load) for HIV is preferred.

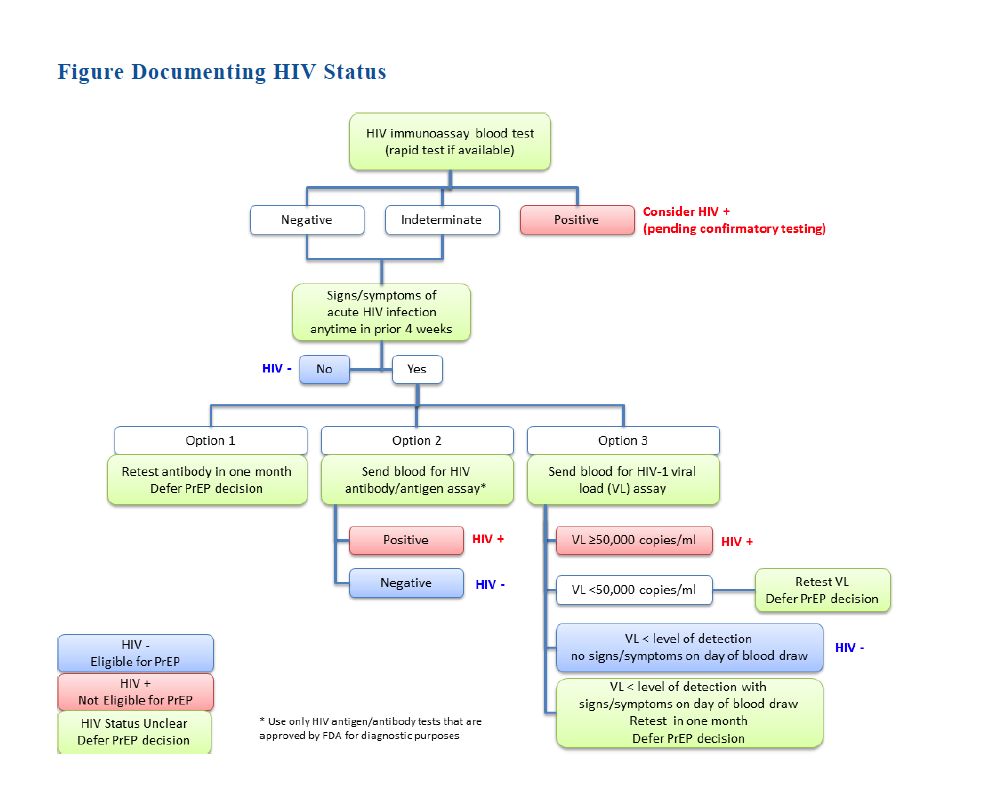

CDC Guidelines recommend the following baseline HIV testing: baseline testing should be conducted with any HIV test other than an oral rapid test, due to that test’s lower sensitivity. (A whole blood rapid test is acceptable.) For patients with signs/symptoms of acute HIV infection within the prior four weeks, the following options are suggested (also see Figure 1, HIV Status Algorithm):

Retest antibody in one month; defer PrEP decision.

Send blood for HIV antibody/antigen assay (i.e., fourth-generation HIV testing). If the patient is negative, it is acceptable to initiate PrEP.

Send blood for HIV-1 viral load (VL) assay. If the patient has VL<50,000 copies/mL, PrEP should be deferred while testing is repeated. If the VL is below the level of detection of the assay, and the patient has no signs/symptoms on that day, it is acceptable to initiate PrEP.

(figure title)

Figure 1. HIV Status Algorithm[1]

In all other scenarios (VL>50,000, which is consistent with a diagnosis of HIV infection; signs/symptoms present on day of blood draw, which is concerning for acute HIV infection), PrEP should be deferred.

Additionally, it is important to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to starting PrEP. Those found to be susceptible to HBV (absence of hepatitis B surface antibody, or sAb, in serum) should be offered HBV vaccination. If active HBV infection is diagnosed, TDF-FTC can be initiated for both HBV treatment and HIV prevention. Later, if TDF-FTC is discontinued for HIV prevention, treatment for active HBV must be continued.

11. What additional support and ongoing assessment are required for patients on PrEP?

As mentioned above, PrEP should be prescribed as part of a combination prevention plan. Studies of PrEP have involved substantial support, including monthly HIV testing and discussions about adherence, safer sex behaviors, and condom use.

At minimum, while patients are on PrEP, CDC Guidelines recommend the following:

Monitoring |

Frequency |

Prevention and medication support |

|

Assess adherence |

At every visit |

Provide risk reduction counseling |

|

Offer condoms |

|

Manage side effects |

|

Laboratory testing |

|

Any testing except oral rapid testing

|

• Every 3 months, and • Whenever there are symptoms of acute infection (serologic screening test and HIV RNA test)

|

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) symptom screen and testing • NAAT (nucleic acid amplification test) to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia, based on exposure site) • Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) • Inspection for anogenital lesions |

Symptom screen: • At every visit |

Testing: • At least every 6 months, even if asymptomatic (Note: Monogamous serodiscordant couples may not need STI screening as frequently) • Whenever symptoms are reported |

|

Hepatitis C Antibody Test |

At least every 12 months for: • People who use drugs • Men who have sex with men • People with multiple sex partners |

Serum creatinine and calculated creatinine clearance |

At 3 months after initiation, then every 6 months |

Urinalysis |

Every 12 months |

Pregnancy testing |

Every 3 months |

12. Will PrEP be covered by my patients’ health insurance?

Most insurance plans and state Medicaid programs are covering TDF-FTC as PrEP. Prior authorization may be required.

Patient assistance program: A commercial medication assistance program* provides free PrEP to people with limited income and no insurance to cover PrEP care. The cost of the medication and some additional screening tests are covered. The paperwork must be signed and submitted by a licensed clinical provider.

Co-pay assistance program: Income is not a factor in eligibility. The paperwork must be signed and submitted by a licensed clinical provider.

(small text at base of page)

* The manufacturer of Truvada (Gilead) has established several programs to help cover the cost of PrEP. Providers can assist their patients by applying for assistance (either for help with the Truvada co-pay if the patient is insured or for complete coverage of the medication if the patient does not have insurance or needs financial assistance).

The application form for Gilead’s patient assistance programs is available at

https://start.truvada.com/Content/pdf/Medication_Assistance_Program.pdf.

13. If I take care of both members of a serodiscordant couple, is it preferable to treat just the HIV-positive partner, just the HIV-negative partner, or both?

Experts recommend that all people with HIV be treated, regardless of clinical status or CD4 cell count.[17, 18] Virologic suppression of the HIV-infected partner protects his or her health and the health of the HIV-uninfected partner.[19] Whether the HIV-negative partner should take PrEP if the positive partner is virologically suppressed is a matter of substantial debate. This decision must be individualized and may depend on the HIV-positive partner’s virologic control, condom use, and other partners that the HIV-negative partner may have.

Factors against providing PrEP to the negative partner if the positive partner has an undetectable plasma viral load includerecent large cohort studies suggesting that the risk of seroconversion in stable, serodiscordant couples may be negligible.[20]

Factors for providing PrEP to the negative partner if the positive partner has an undetectable plasma viral load include the fact that adherence to antiretroviral therapy can lapse, and that there can be differences between plasma and seminal/vaginal fluid viral load measurements at any one time.[21] Additionally, many studies have supported that much HIV transmission is from non-main partners.[19]

For more information: Go to www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf>.

(page 6 (back page ) (References will be checked & re-ordered after content and overall flow is approved)

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A Clinical Practice Guideline. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States. 2014. <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf>.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC). Clinical Providers’ Supplement. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States. 2014. <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf>.

3. Krakower D, Mayer KH. What primary care providers need to know about preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a narrative review. Annals of internal medicine 2012 Oct 2;157(7):490-7.

4. Smith DK, Pals SL, Herbst JH, Shinde S, Carey JW. Development of a clinical screening index predictive of incident HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012 Aug 1;60(4):421-7.

5.

New

York State (NYS). Guidance for the Use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

(PrEP) to Prevent HIV Transmission. 2014 Jan.

<http://www.hivguidelines.org/clinical-guidelines/pre-exposure-prophylaxis/guidance-for-the-use-of-pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep-toprevent-hiv-transmission/>.

6. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England Journal of Medicine 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587-99.

7. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. The New England Journal of Medicine 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399-410.

8. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. The New England Journal of Medicine 2012 Aug 2;367(5):423-34.

9. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among

African women. The New England Journal of Medicine 2012 Aug 2;367(5):411-22. [ref number not incorporated in sequence]

10. Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Nair G et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in women: daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofovir/emtricitabine, or vaginal tenofovir gel in the VOICE study (MTN 003). CROI. Atlanta, GA, 2013.

11. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013 Jun 15;381(9883):2083-90.

12. van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS 2012 Apr 24;26(7):F13-9.

13. Koenig LJ, Lyles C, Smith DK. Adherence to Antiretroviral Medications for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Lessons Learned from Trials and Treatment Studies. American journal of preventive medicine 2013 Jan;44(1 Suppl 2):S91-8.

14. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The Lancet: Infectious Diseases 2014 Sep; 14(9): 820-829.

15. Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013 Sep 1;64(1):79-86.

16. Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Bone mineral density in HIV-negative men participating in a tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized clinical trial in San Francisco. PloS one 2011;6(8):e23688.

17. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents: Department of Health and Human Services, 2013.

18. Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA panel. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 2012 Jul 25;308(4):387-402.

19. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493-505.

20. Rodger A, Bruun T, Cambiano V et al. HIV Transmission Risk Through Condomless Sex If HIV+ Partner On Suppressive ART: PARTNER Study. CROI. Boston, MA, 2014.

21. Gianella S, Smith DM, Vargas MV, et al. Shedding of HIV and human herpesviruses in the semen of effectively treated HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Aug;57(3):441-7.

22. Volk J, Marcus J, Phengrasamy T, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increased Use of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clinical Infectious Diseases (2015) doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778

[logos]

(1) Department of Health and Human Services/CDC Control and Prevention badge

(2) Act Against AIDS logo

(3) PrEP/PEP logo treatment and tag

(footer text)

Content reused with permission from the New York City Department of Health

Doc code # & date (CDC to supply #’s)

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Barbara Huber |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-27 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy