Various Demographic Area Pretesting Activities

Generic Clearance for Questionnaire Pretesting Research

omb1311AFFenc8

Various Demographic Area Pretesting Activities

OMB: 0607-0725

Usability Studies of the American FactFinder Web Site: Baseline compared with Follow-Up

Submitted by:

Erica Olmsted-Hawala, Victor Quach, & Jennifer Romano Bergstrom,

Center for Survey Measurement (CSM)

Submitted to:

Marian Brady

Data Access and Dissemination Systems Office (DADSO)

ABSTRACT

At the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009, the U.S. Census Bureau’s Human Factors and Usability Research group conducted a baseline usability evaluation of the legacy version of the American FactFinder (AFF). In June of 2011 and June-July of 2012, follow-up to the baseline usability studies were conducted on the new redesigned AFF. Tasks were developed to gain an understanding of whether users understood the Web site’s search and navigation capabilities as well as some table and map functions. Results highlight that performance and satisfaction for novice users decreased when on the new redesigned AFF as compared to the legacy site. Performance for experts was about the same on the legacy and on the new redesigned AFF, though satisfaction decreased on the new site. Usability problems are described for each study, and include user issues with the search capabilities of both the legacy and the new redesigned AFF site. This report provides a complete summary of the baseline and follows up usability evaluations, including methods, findings, and comparisons of the three designs of the AFF Web site interface: the legacy version, and the evolving interface of the new AFF. The report also includes suggestions for improving the new site and the team response.

This report is released to inform interested parties of research and to encourage discussion of work in progress. Any views expressed on the methodological issues are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau.

At the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009, the U.S. Census Bureau’s Human Factors and Usability Research group conducted a baseline usability evaluation of the legacy version of the American FactFinder (AFF). In June of 2011 and June-July of 2012, follow-up to the baseline usability studies were conducted on the new redesigned AFF. The testing evaluated the success, efficiency and satisfaction of novice and expert users with the legacy and the newly designed AFF Web site. Testing took place at the Census Bureau’s Usability Laboratory in Suitland, MD.

Purpose: The purpose of the baseline and follow up studies was to discover how the new AFF site performed for users as compared to the legacy site.

Method: Twenty-three (10 novice 13 expert) individuals were recruited to participate in the baseline usability study, 10 novices were recruited to participate in the first follow up (June 2011) to the baseline and 18 individuals (10 novice 8 expert) were recruited to participate in the second follow up to the baseline (June-July 2012). Participants were recruited from State Data Center conference attendees that took place at the Census Bureau Headquarters, by referral, or through a participant database maintained by the Usability Lab. All participants had at least one year of experience navigating Web sites and using a computer. Each participant sat in a small room, facing one-way glass and a wall camera, in front of an LCD monitor equipped with an eye-tracking machine. After finishing the tasks, all participants completed a satisfaction questionnaire and answered debriefing questions. Members from the AFF design team, composed of members from the Data Access and Dissemination Systems Office (DADSO) and IBM, observed several sessions from a television screen and monitor in a separate room.

Participants completed the same tasks in each round of testing so that comparisons could be made. Some tasks assessed how participants would locate information on the Web site, some assessed how participants manipulated data tables, and some assessed how they manipulated maps. While they worked, participants described their actions and expectations aloud while the test administrator observed and communicated from another room.

High-Priority Results:

In general, user performance, with respect to accuracy, efficiency and subjective satisfaction decreased with the new AFF Web site, as compared to the legacy Web site. Novices’ accuracy, efficiency, and satisfaction decreased for the majority of tasks in 2011 and 2012. Experts’ accuracy and efficiency on tasks in 2012 increased, but satisfaction decreased from the 2008 baseline. Usability issues include difficulties with the how to get started (new AFF) difficulties with search (legacy and new AFF), difficulties with the overlays and understanding how the site functions with the “Your Selections” and the “Search Results” areas (new AFF). A complete list of usability issues and suggested recommendations are included in the results section of the report.

Table of Contents

1.0. Introduction & Background 11

2.2 Participants and Observers 14

2.3 Facilities and Equipment 15

2.3.2 Computing Environment 15

2.3.3 Audio and Video Recording 15

2.4.1 Script for Usability Session 15

2.4.3 Questionnaire on Computer and Internet Experience and Demographics 15

2.4.5 Satisfaction Questionnaire 16

2.6 Performance Measurement Methods 17

2.7 Identifying and Prioritizing Usability Problems 17

3.3 Participant Satisfaction 20

3.4.1 Baseline Positive Findings 33

3.4.2 2011 Follow-Up Positive Findings 33

3.4.3 2012 Follow-Up Positive Findings 33

3.5.1 Baseline Study Usability Issues 33

3.5.1a High-Priority Issues 33

3.5.1b Medium Priority Issues 38

3.5.1c Low Priority: Issues 40

3.5.2a High-Priority Issues 42

3.5.2b Medium-Priority Issues 51

3.5.3a High-Priority Issues 52

3.5.3b Medium-Priority Issues 61

Appendix A: Tasks from 2008, 2011, & 2012 68

Appendix B: Participant Demographics 73

Table 14. Novice 2008 participants’ self-reported computer and Internet experience in 2008-2009. 73

Table 15: Novice 2011 participants' self-reported computer and Internet experience in 2011. 74

Appendix E. Questionnaire on Computer Use and Internet Experience 82

Appendix F. Final Satisfaction Questionnaire Baseline and 2011 Follow Up 85

Appendix G: Debriefing Questionnaire for Baseline and Follow Up AFF Usability Tests 88

Appendix H: Participant Accuracy Scores 90

Table 19. Novice 2008 Baseline Accuracy Scores 90

Table 20. Novice 2011 Accuracy Scores 91

Table 21: Novice 2012 Accuracy Scores 92

Table 22: Expert Baseline Accuracy Scores 93

Table 23: Expert 2012 Follow Up Accuracy Scores 94

Appendix I: Participant Efficiency Scores 95

Table 28: Expert 2012 Follow Up: Time in minutes (m) and seconds (s) to complete each task 99

Appendix J: Participant Satisfaction Scores 100

Table 29. Novice 2008 Baseline Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 100

Table 30. Novice 2011 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 101

Table 31: Novice 2012 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 102

Table 32: Expert Baseline Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 103

Table 33: Expert 2012 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 104

Figure 1: Screen shot of Baseline American FactFinder Web site. 9

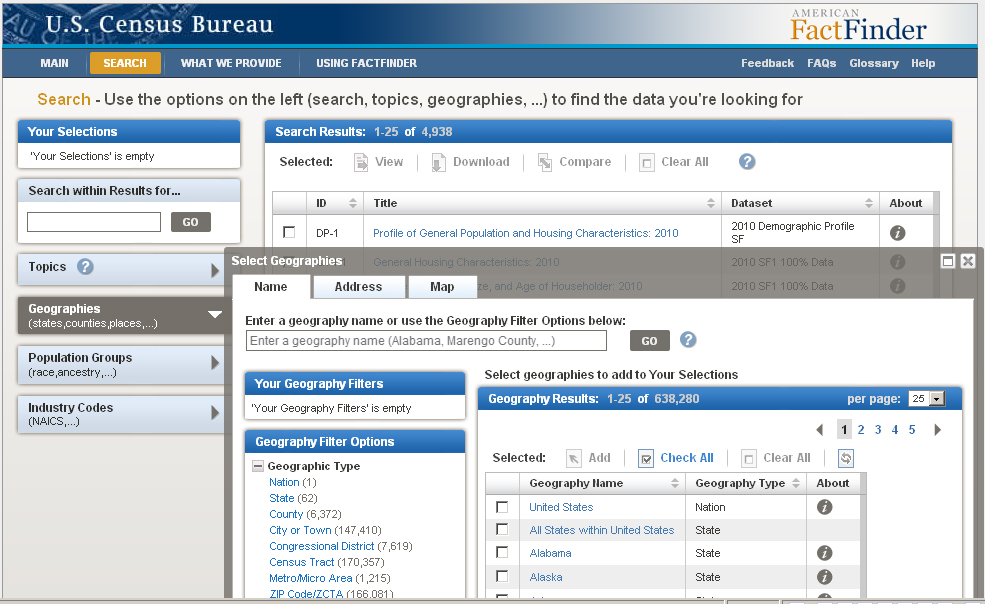

Figure 2: Screen shot of First Follow-Up American FactFinder Web site (June 2011). 10

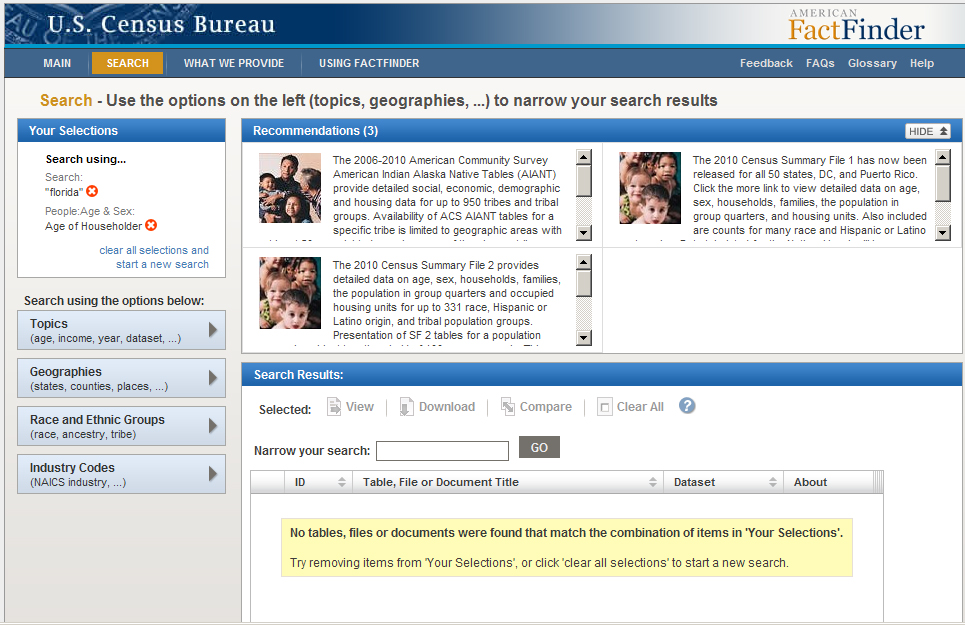

Figure 3: Screen shot of Second Follow-Up American FactFinder Web site (June 2012). 10

Figure 11: Reference map of Fairfax, VA from AFF site, using the FactSheet option. 34

Figure 13: Top navigations on the Baseline AFF Web site. 37

Figure 15: The geography overlay covered the main search results. 39

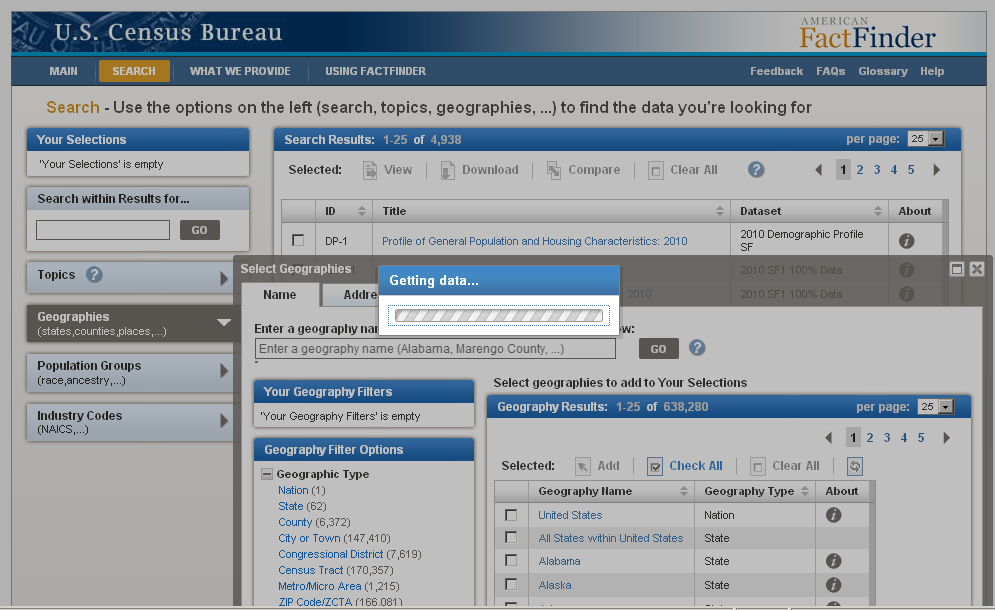

Figure 16: The “getting data” implies the search is getting data. 40

Figure 17: “Search within Results” confused some participants 42

Figure 18: The “Quick Search” off the main page often led to a “no results found.” 43

Figure 20: Screen shot of initial home page that was tested in Iteration 2 (June 2009). 44

Figure 21: Results listed appear to have no relationship to search query: “poverty states 2000.” 46

Figure 22: Suggested wording when users have not entered or chosen any options 49

Figure 24: One participant honed in to the View button after reading these instructions. 52

Figure 25. Suggested message/wording when the “Narrow your search” feature is unavailable. 54

Figure 26: These results are irrelevant to the participant’s query. 55

Figure 27: Health Insurance is returned after a search on health clubs. 56

Figure 28: Users expecting search results may overlook Community Facts 58

Figure 29: Help focuses on the use of FactFinder rather than the contents 59

Figure 30: Participant types Mexico into the Geography box in QS 60

Figure 31: All Counties within Virginia could mean the overall statistic for Virginia 61

Figure 32: Lack of Filtering for American Indian Reservations 61

Table 8: Accuracy Scores for Baseline and 2012 Follow-Up Assessments for Expert Participants 28

Table 9: Efficiency Scores for Baseline, and 2012 Assessments for Experts – Including Failures 29

Table 12: Novice Tasks throughout the Years 68

Table 13: Expert tasks throughout the Years 70

Table 14. Novice 2008 participants’ self-reported computer and Internet experience in 2008-2009. 73

Table 15: Novice 2011 participants' self-reported computer and Internet experience in 2011. 74

Table 19. Novice 2008 Baseline Accuracy Scores 90

Table 20. Novice 2011 Accuracy Scores 91

Table 21: Novice 2012 Accuracy Scores 92

Table 22: Expert Baseline Accuracy Scores 93

Table 23: Expert 2012 Follow Up Accuracy Scores 94

Table 28: Expert 2012 Follow Up: Time in minutes (m) and seconds (s) to complete each task 99

Table 29. Novice 2008 Baseline Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 100

Table 30. Novice 2011 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 101

Table 31: Novice 2012 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 102

Table 32: Expert Baseline Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 103

Table 33: Expert 2012 Follow-Up Satisfaction Results (1 = low, 9 = high). 104

Usability Studies on the American FactFinder: Baseline and Two Annual Follow-Up to the Baseline Studies

1.0. Introduction & Background

The user interface is an important element to the design of a Web site (Nielsen, 1999; Krug, 2006) For a Web site to be successful, the user interface must be able to meet the needs of users in an efficient, effective, and satisfying way. It is the job of the user interface to provide cues and affordances that allow users to get started quickly and to find what they are looking for with ease.

This report specifies the methods, materials, that the Center for Survey Measurement (CSM) Usability Laboratory used to evaluate the usability of the American Fact Finder (AFF) Legacy site (Baseline, shown in Figure 1), the newly launched (2011 Follow-Up, shown in Figure 2) and the live site after some tweaks had been made to the interface (2012 Follow up, shown in Figure 3). The report also provides results of user performance metrics, identifies usability problems and recommendations to improve the evolving user interface of the Web site.

AFF is a free online tool that allows users to find, customize and download Census Bureau data on the population and economy of the United States. AFF is available to the public, and a multitude of diverse users search the site for a vast range of information. AFF underwent a major redesign, and a series of usability tests assessed successive iterations of the Web site (see Romano Bergstrom, Olmsted-Hawala, Chen & Murphy, 2011 for a review). We gathered baseline usability data on the legacy AFF site and conducted a follow-up test when the new site was launched, and then a year later once some design tweaks had been implemented. This paper reports the findings from the baseline 2008 study and compares it with the results from the two follow-up usability studies (conducted in mid 2011 and mid 2012). Where available, the paper highlights the responses from our sponsor, Data Access and Dissemination System Office (DADSO), and IBM (henceforth referred to as the Design Team) to the findings.

Figure 1: Screen shot of Baseline American FactFinder Web site.

Figure 2: Screen shot of First Follow-Up American FactFinder Web site (June 2011).

Figure 3: Screen shot of Second Follow-Up American FactFinder Web site (June 2012).

2.0. Method

Working collaboratively, members of the Design Team and the Usability Team created the tasks, which were designed to capture the participant’s interaction with and reactions to the design and functionality of the AFF Web site. Each task established a target outcome for the user but did not tell the user how to reach the target. We designed the tasks with the goal of using them throughout the series of iterative tests (Romano Bergstrom et al., 2011), as well as throughout the follow-up tests. See Appendix A for the tasks.

2.2 Participants and Observers

Baseline: We conducted usability testing on the baseline AFF Web site from November 25 to December 8, 2008 with ten novice participants. Participants were recruited through a database maintained by the Usability Lab. One participant was removed from the analysis due to inexperience navigating the Internet, as observed during the usability test. The remaining nine novice participants were considered knowledgeable in navigating the Internet and using a computer. The mean age for novice participants was 37.22 years (range 18-60), and the mean education level was 15.22 years of schooling (range 10-18 years). All novice participants were unfamiliar with the AFF Web site. The baseline study of the experts was conducted at two different time periods, however the data and the interface did not change during that time. The first five expert usability sessions were conducted in February of 2009. The remaining seven expert sessions were conducted in October 2009 when the State Data Centers (SDC) and the Census Information Centers (CIC) personnel were in town for the annual conference at the Census Bureau. All expert participants were SDC or CIC members and all were experienced in using the Internet and the American FactFinder Web site. One participant was removed because the power went out and the session could not go forward, thus the analysis is on the twelve expert users. The mean age for expert participants was 46.5 years (range 31-61), and the mean educational level was 18.16 years of schooling (range 16-22).

2011 Follow Up: We conducted usability testing of the 2011 Follow-Up AFF Web site, solely with novice users from June 8 to June 17, 2011. Eight novice-level participants were recruited through our database, and two participants were new interns that fit our novice criteria. One participant was removed from the analysis due to low education level, and we wanted these results to be comparable to the Baseline test results. The remaining nine participants were considered knowledgeable in navigating the Internet and using a computer. The mean age for participants was 38.56 years (range 21-73), and the mean education level was 16.22 years of schooling (range 10-18 years). All participants were unfamiliar with the AFF Web site.

2012 Baseline Follow Up: We conducted usability testing of the 2012 Follow-Up AFF Web site with novice and expert users from June 7 to July 17, 2012. Ten novice-level participants were recruited through our database, and ten expert-level participants were recruited from a combination of State Data conference attendees, emails targeting expert users, our database, and a few internal employees who use AFF in their daily work. All novice participants were unfamiliar with the AFF Web site. The mean age1 for novice participants was 42 (range 16 – 72), and the mean education level was 14.9 years of schooling (range 11-18 years). All expert participants were either familiar with the AFF Web site or other similar statistical data sites. The mean age for expert participants was 44.6 years (range 28-57), and the mean education level was 18 years of schooling (range 16-22 years). See Appendix B for participants’ self-reported computer and Internet experience.

2.3 Facilities and Equipment

Testing took place in the Usability Lab (Room 5K502) at the U.S. Census Bureau in Suitland, MD.

2.3.1 Testing Facilities

The participant sat in a 10’ x 12’ room, facing one-way glass and a wall camera, in front of a standard monitor that was on a table at standard desktop height. During the usability test, the test administrator (TA) sat in the control room on the other side of the one-way glass. The TA and the participant communicated via microphones and speakers.

2.3.2 Computing Environment

The participant’s workstation consisted of a Dell personal computer with a Windows XP operating system, a standard keyboard, and a standard mouse with a wheel. The screen resolution was set to 1024 x 768 pixels, and participants used the Firefox browser.

2.3.3 Audio and Video Recording

Video of the application on the test participant’s monitor was fed through a PC Video Hyperconverter Gold Scan Converter, mixed in a picture-in-picture format with the camera video, and recorded via a Sony DSR-20 Digital Videocassette Recorder on 124-minute, Sony PDV metal-evaporated digital videocassette tape. One desk and one ceiling microphone near the participant captured the audio recording for the videotape. The audio sources were mixed in a Shure audio system, eliminating feedback, and were then fed to the videocassette recorder.

2.4 Materials

2.4.1 Script for Usability Session

The TA read some background material and explained several key points about the session. See Appendix C.

2.4.2 Consent Form

Prior to beginning the usability test, the participant completed a consent form. See Appendix D.

2.4.3 Questionnaire on Computer and Internet Experience and Demographics

Prior to the usability test, the participant completed a questionnaire on his/her computer and Internet experience and demographics. See Appendix E.

2.4.4 Tasks

In the Baseline study, novice participants performed 10 pre-determined tasks on the Web site (Appendix A). The tasks were developed by members of the Design Team and the Usability Team to assess the ease of use and accuracy of finding information on the AFF Web site. Seven of the tasks were considered “simple,” and three were considered “complex”. Expert participants performed six pre-determined tasks on the Web site. All expert tasks were more complex than the novice tasks.

In the First Follow-Up study (mid 2011), novice participants performed six pre-determined tasks on the Web site. These tasks were originally developed for the Baseline study with the intention that we would reuse them in subsequent Follow-Up studies. However, the tasks were modified slightly to reflect content that was available on the site. For example, a year range was modified from 2000 to 2010 because 2010 data had been loaded into the site but 2000 data had not. Four of the tasks were considered “simple,” and two were considered “complex.” In the First Follow-Up study we did not have expert users.

In the Second Follow-Up study (mid 2012), novice participants performed 10 per-determined tasks on the Web site, however due to the increased amount of time that it was taking to complete the tasks, not all participants were able to complete all 10 tasks. The tasks were slightly modified to reflect content that was available on the site. Expert participants performed the same (with minor changes) six tasks that had been used in the 2008 Baseline study.

Tasks used in the Follow-Up studies of 2011 and 2012 are comparable with the tasks used in the original 2008 Baseline study, where the tasks differ it is noted in Appendix A.

2.4.5 Satisfaction Questionnaire

Members of the Usability Lab created the Satisfaction Questionnaire, which is loosely based on the Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction (QUIS, Chin, Diehl, & Norman, 1988). In typical usability tests at the Census Bureau, we use satisfaction items that are tailored to the particular user interface we are evaluating. In the first two studies, the Satisfaction Questionnaire included 10 items worded for the AFF Web site, in the 2012 Follow-Up study, the satisfaction questionnaire had been modified slightly. See Appendix F for the questionnaires.

2.4.6 Debriefing Questions

After completing all tasks, the participant answered debriefing questions about his/her experience using the AFF Web site. See Appendix G.

2.5 Procedure

Following security procedures, external participants individually reported to the visitor’s entrance at the U.S. Census Bureau Headquarters and were escorted to the Usability Lab. Internal participants met the TA at the Usability Lab. Upon arriving, each participant was seated in the testing room. The TA greeted the participant and read the general introduction. Next, the participant read and signed the consent form. After signing the consent form, the participant completed the Questionnaire on Computer and Internet Experience and Demographics. The TA left the Satisfaction Questionnaire on the desk beside the participant and left the testing room. While the TA went to the control room to perform a sound check, the participant completed the Questionnaire on Computer and Internet Experience and Demographics. The TA then began the video recording. The Internet browser was pre-set to the AFF Web site (http://factfinder.census.gov for the Baseline and http://factfinder2.census.gov for the Follow-Up studies). The TA instructed the participant to being by reading the first task aloud and to proceed.

While completing the tasks, the TA encouraged the participants to think aloud and to share their thoughts about the Web site following a traditional or speech communication think-aloud protocol (Olmsted-Hawala, Murphy, Hawala, & Ashenfelter, 2010). The participant’s narrative allowed us to gain a greater understanding of how the participant used the Web site and to identify issues with the site. If at any time the participant became quiet, the TA reminded the participant to think aloud, using prompts such as “Keep talking,” and “Um hum?” During the sessions, the TA noted any behaviors that indicated confusion, such as hesitation, backtracking, and comments. After survey completion, the TA asked the participant to complete the Satisfaction Questionnaire.

While the participant completed the Satisfaction Questionnaire, the TA met with the observers to see if they had any additional questions for the participant. The TA then returned to the testing room to ask debriefing questions (Appendix G). This debriefing provided an opportunity for a conversational exchange with participants. The TA remained neutral during this time to ensure that they did not influence the participants’ reactions to the Web site. At the conclusion of the debriefing, the TA stopped the video recording. Overall, each usability session lasted approximately 60 minutes. Participants who were not government employees were given $40 each.

Typically, goals are defined prior to usability testing. However, since these tests were a baseline and follow-up to the baseline, the goal was to see how well the evolving new site performed compared to the legacy site (as tested in the baseline). Thus, no usability goals were set. Instead, we make performance comparisons between the sites in terms of participant accuracy, efficiency and subjective satisfaction, and we identify areas of the AFF Web site that were problematic and frustrating to participants.

2.6 Performance Measurement Methods

For the baseline (2008) and Follow-Up usability studies (2011 & 2012) the performance measurements consisted of task accuracy, task efficiency and subjective satisfaction.

2.6.1 Accuracy

After each participant completed a task, the TA rated it as a success or a failure. In usability testing, successful completion of a task means that the design supported the user in reaching a goal. Failure means that the design did not support task completion.

2.6.2 Efficiency

After all usability tests were complete, the TA calculated the average time taken to complete each task. Average times were calculated across all participants for each task and across all tasks for each participant.

2.6.3 Satisfaction

After completing the usability session, each participant completed the tailored ten-item satisfaction questionnaire. Participants were asked to rate their overall reaction to the site by circling a number from 1 to 9, with 1 being the lowest possible rating and 9 the highest possible rating. Other items on the questionnaire included assessing the screen layouts, the use of terminology on the Web site, the arrangement of information on screens, ease of navigation, and the overall experience of finding information. See Appendix F. The Usability Team calculated ranges and means for the various rated attributes of the Web site.

2.7 Identifying and Prioritizing Usability Problems

To identify design elements that caused participants to have problems using the Web site, the TA recorded detailed notes during the usability session. When notes were not conclusive, the TA used the videotape recordings from each session to confirm or disconfirm findings. By noting participant behavior and comments, the Usability Team inferred the likely design element(s) that caused participants to experience difficulties. The team then grouped the usability issues into categories based on severity and assigned each problem a priority code, based on its effect on performance. The codes are as follows:

High Priority – These problems have the potential to bring most users to a standstill. Most participants could not complete the task.

Medium Priority – These problems caused some difficulty or confusion, but most participants were able to successfully complete the task.

Low Priority – These problems caused minor annoyances but did not interfere with the tasks.

3.0 Results

In this section, we discuss the findings from the usability studies. We present the qualitative and quantitative data, usability issues, and possible future directions based on the Design Team’s responses to the findings.

3.1 Participant Accuracy

Participant accuracy is divided up into novice accuracy scores and expert accuracy scores.

3.1a Novice

In the Baseline study, the overall accuracy score for novice participants on the simple tasks was 55% and the overall accuracy score for novice participants on the complex tasks was 27%. Accuracy scores for simple tasks ranged from 29% to 100% across participants, and accuracy scores for complex tasks ranged from 0 to 100% across participants. For simple tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 22% to 89% across tasks, and for complex tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 22% to 38% across tasks. Accuracy scores for complex tasks were low compared to typical usability studies (we generally aim for an 80% accuracy goal). It appears that participants struggled the most with the complex tasks. Almost half of the participants (44%; 4 out of 9) did not complete the complex tasks correctly.

In the 2011 Follow-Up study, the overall accuracy score for novice participants on the simple tasks was 29%, and the overall accuracy for complex tasks was 28%. Accuracy scores for simple tasks ranged from 0 to 94% across participants, and accuracy scores for complex tasks ranged from 0 to 100% across participants. For simple tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 11% to 44% across participants, and for complex tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 11% to 44% across participants. Accuracy scores for simple tasks mostly decreased from the baseline to the 2011 Follow-Up; however, there was one simple task that showed a slight increase in performance. For the two complex tasks tested in the Baseline, one showed an increase in accuracy, and one showed a decrease in the 2011 study.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study, the overall accuracy score for novice participants on the simple tasks was 14%, and the overall accuracy for novice complex tasks was 54%. Accuracy scores for simple tasks ranged from 0% to 68.8%, and accuracy scores for novice complex tasks ranged from 0% to 100% across participants. For simple tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 0% to 80% across participants, and for novice complex tasks, accuracy scores ranged from 16.7% to 90% across participants. Accuracy scores for the simple tasks decreased from the baseline. One complex task improved in the 2012 testing, because the Quick Start feature worked effectively for participants.

Table 1 and Figure 4 illustrate the comparison of accuracy scores across the three studies (e.g., Baseline, 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up studies). As can be seen in the visuals, participants in both the 2011 and 2012 studies had more difficulties with the simple tasks than participants in the Baseline. This highlights a need for a simple route into data for novice participants. See Appendix A for the tasks and Appendix H for accuracy by participant.

3.1b Expert

In the Baseline study, the overall accuracy score for expert participants was 47%. Accuracy scores ranged from 0% to 100% across participants, and from 36 to 69% across tasks.

No testing was done with experts on the 2011 Follow-Up study since resources were re-focused on iterative usability tests aimed at improving the design of the new AFF interface.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study, the overall accuracy score for expert participants on the tasks was 49.22%, Accuracy scores ranged from 0 to 100%, across participants. And from 37.50% to 72.20% across tasks.

Accuracy scores appear to have ncreased from Baseline to 2012 Follow-Up, although the increase may not be statistically significant. The wide range of performance by participants seems to indicate that success with American FactFinder can be improved with more extensive use of the site, as the SDC and CIC participants who have been using the interface on a more constant basis outperformed other expert users.

See Table 8 and Figure 6 for accuracy score comparisons from Baseline to 2012 Follow Up. See Appendix A for the tasks and Appendix H for detailed accuracy by participant.

3.2 Participant Efficiency

Participant efficiency is separated into novice efficiency scores and expert efficiency scores.

3.2a Novice

In the Baseline study, the average time for novice participants to complete simple tasks (for correctly completed tasks only) was 3 minutes 45 seconds, and the average time novice participants took to complete complex tasks was 5 minutes 55 seconds. Time to complete simple tasks ranged from 28 seconds to 14 minutes 30 seconds, and time to complete complex tasks ranged from 1 minute 38 seconds to 13 minutes 56 seconds, across participants. This timing calculation was based on 44 simple-task responses (79%) and 9 complex-task responses (35%) that were answered correctly. The task failures were not included in the efficiency scores.

In the 2011 Follow-Up study, the average time to complete simple tasks (for correctly completed tasks only) was 6 minutes 46 seconds, and the average time to complete complex tasks was 4 minutes 37 seconds. Time to successfully complete simple tasks ranged from 45 seconds to 14 minutes 29 seconds, and time to successfully complete complex tasks ranged from 2 minute 9 seconds to 10 minutes 54 seconds, across users.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study, the average time for novice participants to complete simple tasks (for correctly completed tasks only) was 6 minutes 46 seconds, and the average time novice participants took to complete complex tasks was 6 minutes 15 seconds. Time to successfully complete simple tasks ranged from 1 minute 10 seconds to 9 minutes 58 seconds, and time to successfully complete complex tasks ranged from 2 minutes 42 seconds to 8 minutes, across participants.

Time to complete tasks took longer for the simple tasks in both the 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up studies than they did in the Baseline study. For the 2011 Follow-Up study, of the two complex tasks tested, one showed an increase in time and the other showed a decrease in the amount of time it took to complete the task2. Time to complete complex tasks also took longer in the 2012 Follow-up study than in the Baseline.

See Table 3 and Table 5 for comparison of efficiency scores across the three studies and Appendix I for detailed participant efficiency scores.

3.2b Expert

In the Baseline study, the average time for expert participants to complete tasks (for correctly completed tasks only) was 9 minutes 02 seconds. Time to successfully complete tasks ranged from 3 minutes, 38 seconds to 23 minutes 3 seconds.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study3, the average time for expert participants to complete tasks (for correctly completed tasks only) was 6 minutes 13 seconds. Time to successfully complete tasks ranged from 2 minutes 24 seconds to 14 minutes 25 seconds. Compared to the legacy site tested in the 2008 Baseline, the new site, tested in the 2012 Follow-up study proved quicker for participants who were successful in completing their tasks.

See Table 9 and Table 10 for comparison of efficiency scores across novice participants in the Baseline and 2012 Follow-Up study and Appendix I for detailed participant efficiency scores.

3.3 Participant Satisfaction

Participant satisfaction below is separate by novice and expert satisfaction ratings.

3.3a Novice

In the Baseline study, the average satisfaction score of novice participants’ overall reaction to the site was 6.22 out of 9, which is above the median point on the scale. The highest mean rating was 6.78 on forward navigation (range: impossible - easy). Fifteen percent of the individual participant mean ratings were below the 5-point median. Ratings below the mid-point of the scale indicate issues that may affect many users.

In the 2011 Follow-Up study, the average satisfaction score of participants’ overall reaction to the site was 3.33 out of 9, which is below the median and lower than participants’ satisfaction in the Baseline study. Consistent with the Baseline study, the highest rating was for forward navigation, with an average rating of 6.13 out of 9. The lowest rating of 2.11 out of 9 was on the overall ease or difficulty of finding information on the site.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study, the average satisfaction score of novice participants’ overall reaction to the site was 3.20 out of 9, which is below the median; lower than participants’ satisfaction in the Baseline study and only slightly lower than the 2011 Follow-Up. The highest rating was for arrangement of information on the screens at 6.10. The lowest rating of 1.60 out of 9 was on the overall ease or difficulty of finding information on the site.

For the 2011 Follow-Up study participants’ self-rated satisfaction decreased for all satisfaction questionnaire items when compared to the Baseline. It was much the same with the 2012 Follow-Up study with the exception of “arrangement of information on the screen” which was higher in 2012 than in Baseline. When compared to the 2011 Follow-Up study some participants were more satisfied with the 2012 version when it came to “information displayed on the screens” and “arrangement of information on the screens”. For other items such as “overall reaction to the web site,” ratings across both Follow Up studies were similar (3.33 in 2011 and 3.20 in 2012). In general, these lower satisfaction scores in both Follow-Up studies, indicate a greater sense of dissatisfaction with the new AFF Web as opposed to the Legacy site. Further, these scores indicate that there are some ongoing frustrations with the new design of the AFF Web site.

See Table 7 and Figure 5 for a comparison of novice satisfaction scores from Baseline to the Follow-Up studies. See Appendix J for detailed user satisfaction results.

3.3b Expert

In the Baseline study, the average satisfaction score of expert participants’ overall reaction to the site was 6.5 out of 9, which is above the median point of the scale. The highest mean rating was 6.92 out of 9 on information displayed on a screen (range Inadequate to Adequate). The lowest rating was 5.17 out of 9 on whether tasks can be performed in a straight-forward manner (range Never to Always).

In the 20124 Follow Up, the average satisfaction score for expert participants’ overall reaction to the site was 4.60 out of 9, which is lower than the median and lower than participants’ satisfaction in the Baseline study. The highest mean rating was 5.50 out of 9, for forward navigation. This was a decrease from 6.42 from the Baseline. The lowest mean rating was a 3.80. This was a decrease from 5.17 in the Baseline.

In the 2012 Follow-Up study, participants’ self-rated satisfaction decreased for all satisfaction questionnaire items. This indicates a lingering sense of dissatisfaction with the new site, even though expert performance from Baseline to 2012 Follow Up appears to have increased in 4 out of 6 tasks.

See Table 11 and Figure 7 for comparison of satisfaction scores from Baseline to 2012 Follow Up. See Appendix J for detailed user satisfaction results.

Novice Tables and Figures

Table 1: Accuracy Scores for 2008 Baseline and 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up Assessments for Novice Participants

|

TASK |

|

|||||||||||

Simple Tasks |

Complex Tasks |

||||||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

Overall success rate |

Simple tasks success rate |

Complex tasks success rate |

2008 Baseline |

89% |

56% |

78% |

78% |

67% |

67% |

33% |

22% |

22% |

38% |

55% |

67% |

27% |

2011 Follow Up |

44% |

21% |

|

|

|

25% |

38% |

11% |

|

44% |

29% |

29% |

28% |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

45% D |

35% D |

|

|

|

42% D |

5% I |

11% D |

|

6% I |

26% D* |

38% D* |

1% I* |

2012 Follow Up |

80% |

0% |

11% |

22% |

0% |

32% |

25% |

17% |

0% |

90% |

35% |

14% |

54% |

Difference in Performance from 2008 |

9% D |

21% D |

67% D |

56% D |

67% D |

35% D |

8% D |

5% D |

22% D |

52% I |

20% D |

53% D |

27% I |

NOTE: I = Increase in accuracy. D = Decrease in accuracy.

Table 2: Repeated Tasks Accuracy Scores for 2008 Baseline and 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up Assessments for Novice Participants

|

TASK |

|

|||||||

Simple Tasks |

Complex Tasks |

||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

10 |

Overall success rate |

Simple tasks success rate |

Complex tasks success rate |

2008 Baseline |

89% |

56% |

67% |

33% |

22% |

38% |

51% |

61% |

30% |

2011 Follow Up |

44% |

21% |

25% |

38% |

11% |

44% |

29% |

29% |

28% |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

45% D |

35% D |

42% D |

5% I |

11% D |

6% I |

22% D* |

32% D* |

2% D* |

2012 Follow Up |

80% |

0% |

32% |

25% |

17% |

90% |

41% |

34% |

54% |

Difference in Performance from 2008 |

9% D |

21% D |

35% D |

8% D |

5% D |

52% I |

17% D |

32% D |

24% I |

*Calculated from the repeated tasks mean.

Simple

tasks

Complex

tasks

Figure 4:

Accuracy Scores from 2008 Baseline and 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up

Assessments, novice participants only.

Participants had more

difficulties with the simple tasks in the 2011 and 2012 Follow-Up

studies than they did in the Baseline study.

Table 3: Efficiency Scores (amount of time per task) for 2008, 2011, and 2012 Novices – Including Failures

|

TASK |

|

|||||||||||

Simple Tasks |

Complex Tasks |

||||||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

Overall* |

Simple tasks* |

Complex tasks* |

2008 Baseline |

1m59s |

4m31s |

2m07s |

2m03s |

5m |

6m52s |

5m15s |

6m49s |

5m59s |

4m47s |

4m32s |

3m58s |

5m52s |

2011 Follow Up

|

4m32s |

9m20s |

|

|

|

9m35s |

7m21s |

7m33s |

|

6m08s |

7m25s |

7m42s |

6m50s |

Difference in performance from 2008^ |

2m33s I |

4m49s I |

|

|

|

2m43s I |

2m6s I |

44s I |

|

1m21s I |

2m23s I |

3m03s I |

1m3s I |

2012 Follow Up |

3m04s |

6m22s |

6m57s |

5m24s |

5m38s |

7m52s |

6m47s |

5m35s |

5m48s |

4m16s |

5m46s |

6m |

5m12s |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

1m05s I |

1m51s I |

4m50s I |

3m19s I |

38s I |

1m I |

1m31s I |

1m13s I |

11s D |

31s D |

1m27s I |

2m02s I |

40s D |

NOTE: I = Increase in time, it took longer to complete the task. D = Decrease in time, it took a shorter amount of time to complete the task.

^ We usually do not include failures in the calculated time to complete tasks, but since the performance was so low in the Follow-Up study, we calculated these times here.

Table 4: Efficiency Scores (amount of time per tasks repeated in 2008, 2011, and 2012) Novices – Including Failures

|

TASK |

|

|||||||

Simple Tasks |

Simple Tasks |

||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

10 |

Overall* |

Simple tasks* |

Complex tasks* |

2008 Baseline |

1m59s |

4m31s |

6m52s |

5m15s |

6m49s |

4m47s |

5m02s |

4m39s |

5m48s |

2011 Follow Up

|

4m32s |

9m20s |

9m35s |

7m21s |

7m33s |

6m08s |

7m25s |

7m42s |

6m50s |

Difference in performance from 2008^ |

2m33s I |

4m49s I |

2m43s I |

2m6s I |

44s I |

1m21s I |

2m23s I |

3m03s I |

1m3s I |

2012 Follow Up |

3m04s |

6m22s |

7m52s |

6m47s |

5m35s |

4m16s |

5m59s |

6m01s |

4m56s |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

1m05s I |

1m51s I |

1m I |

1m31s I |

1m13s I |

31s D |

1m27s I |

2m02s I |

40s D |

Table 5: Efficiency Scores for 2008, 2011, and 2012 Novices - Correct Responses Only

|

TASK |

|

|||||||||||

Simple Tasks |

Complex Tasks |

||||||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

Overall* |

Simple tasks* |

Complex tasks* |

2008 Baseline |

1m45s |

2m02s |

2m07s |

39s |

3m24s |

3m09s |

4m06s |

8m01s |

10m49s |

4m14s |

4m02s |

2m28s |

7m41s |

2011 Follow-Up |

3m58s |

10m26s** |

|

|

|

9m34s |

7m26s |

4m7s** |

|

4m44s |

6m42s |

7m51s*** |

4m26s**** |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

2m12s I |

8m24s I |

|

|

|

6m24s I |

3m19s I |

3m54s D |

|

30s I |

2m49s I |

5m05 I |

1m42s D |

2012 Follow-Up |

2m35s |

- |

- |

2m45s |

- |

9m58s |

7m46s |

8m |

- |

4m25s |

5m55s |

5m46s |

6m13s |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

50s I |

-

|

- |

|

- |

6m49s I |

3m40s I |

1s D |

- |

11s I |

2m02s I |

3m I |

06s I |

NOTE: I = Increase in time, it took longer to complete the task. D = Decrease in time, it took a shorter amount of time to complete the task.

NOTE: Efficiency scores may be skewed due to a limited number of successes

*Mean does not include the tasks from Baseline that were not included in the Follow-Up study.

**Based on 1 correct response out of 9 possible correct responses.

***Based on 10 out of 36 possible correct simple task responses.

****Based on 5 out of 18 possible correct complex task responses.

Table 6: Efficiency Scores for tasks repeated in 2008, 2011, and 2012 Novices - Correct Responses Only

|

TASK |

|

|||||||

Simple Tasks |

Complex Tasks |

||||||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

10 |

Overall* |

Simple tasks* |

Complex tasks* |

2008 Baseline |

1m45s |

2m02s |

3m09s |

4m06s |

8m01s |

4m14s |

3m53s |

2m46s |

6m07s**** |

2011 Follow-Up |

3m58s |

10m26s** |

9m34s |

7m26s |

4m7s** |

4m44s |

6m42s |

7m51s*** |

4m26s**** |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

2m12s I |

8m24s I |

6m24s I |

3m19s I |

3m54s D |

30s I |

2m49s I |

5m05 I |

1m42s D |

2012 Follow-Up |

2m35s |

- |

9m58s |

7m46s |

8m |

4m25s |

5m55s |

5m46s |

6m13s |

Difference in performance from 2008 |

50s I |

-

|

6m49s I |

3m40s I |

1s D |

11s I |

2m02s I |

3m I |

06s I |

***Based on 10 out of 36 possible correct simple task responses.

****Based on 5 out of 18 possible correct complex task responses.

Table 7: Self-Rated Satisfaction Scores for 2008, 2011, and 2012 Novices (1 to 9 where 1 = low and 9 = high)

|

Satisfaction Questionnaire Item |

|||||||||

Iteration |

Overall reaction to site: terrible - wonderful |

Screen layouts: confusing - clear |

Use of terminology throughout site: inconsistent - consistent |

Information displayed on the screens: inadequate - adequate |

Arrangement of information on the screens: illogical - logical |

Tasks can be performed in a straight-forward manner: never - always |

Organization of information on the site: confusing - clear |

Forward navigation: impossible - easy |

Overall experience of finding information: difficult - easy |

Census Bureau specific terminology: too frequent - appropriate |

2008 Baseline |

6.22 |

6.22 |

6.22 |

6.56 |

5.33 |

5.44 |

6.33 |

6.78 |

5.78 |

6.78 |

2011 Follow Up |

3.33 |

2.89 |

5.67 |

3.33 |

4.00 |

2.67 |

2.56 |

6.13 |

2.11 |

4.56 |

Difference in Satisfaction ratings from 2008 |

2.89 D |

3.33 D |

0.55 D |

3.23 D |

1.33 D |

2.77 D |

3.77 D |

0.65 D |

3.67 D |

2.22 D |

2012 Follow Up |

3.20 |

4.10 |

5.00 |

4.40 |

6.10 |

2.60 |

3.60 |

5.10 |

1.60 |

3.90 |

Difference in Satisfaction ratings from 2008 |

3.02 D |

2.12 D |

1.22 D |

2.16 D |

.77 I |

2.84 D |

2.73 D |

1.68 D |

4.18 D |

2.88 D |

NOTE: D = Decrease in rating

Figure 5:

Satisfaction ratings from Baseline and Follow-Up Studies.

Novice

participants are more dissatisfied with the new AFF as compared to

the Legacy site.

Scoring was on a 9-point scale where 1 = low

and 9 = high.

Expert Tables and Figures

Table 8: Accuracy Scores for Baseline and 2012 Follow-Up for Expert Participants5

|

Tasks |

|

|||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Overall success rate |

Baseline |

42% |

50% |

36% |

41% |

69% |

44% |

47% |

2012 Follow Up |

50% |

40% |

43% |

79% |

72% |

38% |

54% |

Difference in performance |

8% I |

10% D |

7% I |

38% I |

3% I |

7% D |

7% I |

NOTE: I = Increase in accuracy. D = Decrease in accuracy.

Figure 6: Accuracy Scores from Baseline and 2012 Assessments for expert participants only. 2012 Performance improved on 4 out of 6 tasks.

Table 9: Efficiency Scores for Baseline, and 20126 for Experts – Including Failures

|

Tasks |

|

|||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Overall |

Baseline |

11m04s |

07m44s |

06m22s |

08m12s |

09m29s |

10m41s |

08m55s |

2012 Follow Up |

08m26s |

07m29s |

08m00s |

05m32s |

08m00s |

05m37s |

07m11s |

Difference in performance |

2m38s D |

14s D |

1m38s I |

2m40s D |

1m29s D |

5m04s D |

1m45s D |

NOTE: I = Increase in time. D = Decrease in time.

Table 10: Efficiency Scores for Baseline, and 20127 for Experts – Correct Responses Only

|

Tasks |

|

|||||

Iteration |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Overall |

Baseline |

14m45s |

07m58s |

05m21s |

07m25s |

09m48s |

10m12s |

09m15s |

2012 Follow Up |

07m04s |

06m28s |

06m34s |

04m43s |

08m16s |

04m55s |

06m20s |

Difference in performance |

7m41s D |

1m30s D |

1m13s I |

2m42 D |

1m32s D |

5m17s D |

2m 55s D |

NOTE: I = Increase in time. D = Decrease in time.

NOTE: Efficiency scores may be skewed due to a limited number of successes

Table 11: Self-Rated Satisfaction Scores for Baseline and 20128 Follow-Up for Experts (1 to 9 where 1 = low and 9 = high)

|

Satisfaction Questionnaire Item |

|||||||||

Iteration |

Overall reaction to site: terrible - wonderful |

Screen layouts: confusing - clear |

Use of terminology throughout site: inconsistent - consistent |

Information displayed on the screens: inadequate - adequate |

Arrangement of information on the screens: illogical - logical |

Tasks can be performed in a straight-forward manner: never - always |

Organization of information on the site: confusing - clear |

Forward navigation: impossible - easy |

Overall experience of finding information: difficult - easy |

Census Bureau specific terminology: too frequent - appropriate |

Baseline |

6.5 |

6.083 |

6.67 |

6.92 |

5.17 |

5.58 |

6.25 |

6.42 |

5.67 |

6.58 |

2012 Follow Up |

4.60 |

5.30 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

5.10 |

3.80 |

4.50 |

5.50 |

3.70 |

4.90 |

Difference in Satisfaction rating |

1.90 D |

.78 D |

1.67 D |

1.92 D |

.07 D |

1.78 D |

1.75 D |

.92 D |

1.97 D |

1.68 D |

NOTE: D = Decrease in ratings.

Figure 7:

Satisfaction ratings from expert participants in the Baseline and

2012 Follow-Up Assessment.

Expert participants were more

dissatisfied with the 2012 Web site.

Scoring was on a 9-point

scale where 1 = low and 9 = high.

3.4 Positive Findings

3.4.1 Baseline Positive Findings

During the test, most users attended to the left navigation and used it often. During debriefing, most users said that they liked the left navigation and found it to be useful and helpful to complete tasks.

During debriefing, most users said that they liked the overall layout and colors of the Main page of the Web site.

Users said that they liked that there was a lot of information available to them, overall.

Users attended to and used the Fact Sheet on the Main page. During debriefing, many users commented that they liked the Fact Sheet.

Most users described the tasks as being pretty easy to complete.

3.4.2 2011 Follow-Up Positive Findings

Participants said that they liked that there was a lot of information available to them on the site.

One participant with a BA in Political Science was able to understand how the interface worked and consequently was successful in searching for content and finding the specific information he was interested in.

One participant said, about the look and feel of the page, that it looked like it would be useful.

One participant said that she was immediately able to see a topic that she was looking for.

3.4.3 2012 Follow-Up Positive Findings

The Quick Facts and Popular Tables on the main page appears to be a way for novice users to get to simple data. We noticed some novice participants using these links. Some novice participants noticed them only after other areas of the main page (i.e., Quick Start) did not work for them. It is likely that once some learning takes place on the site that novice participants would more quickly use these two areas of the main page to get quick data.

Participants saw the type ahead and occasionally clicked on one of the suggestions.

Dataset in Topics helped three expert users complete the majority of the tasks.

Geography List was useful for expert users. One user commented, “[I] really like the list feature. It’s time-saving.”

3.5 Usability Problems

3.5.1 Baseline Study Usability Issues

3.5.1a High-Priority Issues

Testing identified two general high-priority usability issues. Medium and low-priority findings follow.

1. The Search function was not helpful to participants. Users said that they wanted the search function to help them when they could not find answers, but it seldom did. Users tend to use their knowledge and experience from other Web sites to make inference about new experiences with Web sites (Forsythe, Grose & Ratner, 1998, p.27). Many users begin every online activity “with a Google search” (Krug, p.85). People in this study said they expected search to work like a Google search.

Sometimes, when participants entered items in the search box at the AFF site, no results were returned. For example, for Novice Task 9, (i.e., Which country Idaho increased exports to from 2003 to 2004) two participants tried to use the search function to find the information. One novice participant typed “Idaho export 2003” in the search box, and it returned no results. However, in Google, when one enters “Idaho export 2003” in the search box, many (about 729,000) results are returned. See Figure 8 for a screen shot of the AFF site and the Google site when performing this search.

Other times, when participants used search in AFF, the massive number of results was overwhelming and not helpful. The titles were oftentimes the same for every item on the search results, and the explanation for each item was not informative. For example, for Novice Task 2, (Which three states had most people living in poverty) three participants tried to use the search function to find the information. One participant typed into the search “poverty in 2006.” Many results were returned; however, the information associated with the results was not helpful to the participants in enabling them to determine which selection would have the information they were seeking. In Google, when a user enters a term, such as “poverty in 2006,” a brief explanation follows the titles of the search results, which gives the user enough information to make inferences about the content of the search results. See Figure 9 for a screen shot of the AFF site and the Google site when performing this search. As shown, the first two results on Google are Census Bureau products, but the explanation that Google provides is much more informative to users than are the explanations that the AFF Web site provides.

For expert users, the search also did not work the way they anticipated it would. Most experts also expected the search to be similar to Google, thus said they were frustrated when the search returned “no results.” In addition, expert users had some difficulty when using the keyword search. Expert participants did not notice the option to check the synonyms box when they were searching and many times came up with a “no results” response when searching for a topic that should have had related content (e.g., On expert task 6 the number of health clubs in a few VA counties). A number of experts searched the NAICS for data on “gyms” or “health clubs” and found “no results.” All experts understood that they were doing a NAICS search and just had to get the right key word to match what NAICS coded it, but only one expert appeared to know about checking the synonyms box. In fact, another expert user recommended creating a synonym-type search but thought it would need OMB approval and it would be a long and difficult process to get approved. Two other experts mentioned that if they had been in their work environment they would have turned to a book they have of all NAICS codes.) One SDC employee said about the search “[it] is clumsy; you almost have to know the exact table you want. It could be improved.”

a.

b.

Figure 8: Screen shot of AFF site (a.) and Google site (b.) when performing a search for “Idaho export 2003.”

a.

b.

Figure 9: Screen shot of AFF site (a.) and Google site (b.) when performing a search for “poverty in 2006.”

Recommendation: Improve the search capabilities. Automatically search using synonyms so that user defined terms return related content. Improve the algorithm that determines the results so more results are returned when users enter common words and phrases. As users are expecting the search function to work like other search functions on other sites, the way users enter terms into a search box should be allowed and anticipated. Improve the titles and the explanations that follow each item in the search results. One participant recommended providing a synopsis of the results. Another participant recommended having a search box on every page.

Team Response: In the new AFF, the Search will work completely differently. Users will type a geography and topic, and the system will find that intersection. It will be a clearer path of refining results once you have them. Users will also be able to add ways to narrow results, and the system will give suggestions/hints on how to narrow results.

2. Manipulating and working with maps was not easy. Reference Maps were difficult to use and the grey writing on the maps (against the grey background) was difficult to read. Three novice participants tried to obtain a city map by typing in the city name in the address box but were frustrated when they could not access the city map and instead were prompted for a zip code. The only way to get to a specific city is to zoom in on a specific area of the map, which many novice participants said was frustrating and took a long time. See Figure 10 for a screen shot of the current maps on AFF. One novice participant typed Fairfax, VA in the Fact Sheet box and then clicked on Reference Map. This participant did not have any problems with the map, although the map they received had little detail. See Figure 11 for the map found by using this alternate navigation.

Both expert and novice participants mentioned how the maps were “clunky” or not as easy or as precise as what they were familiar with, such as Google maps or MapQuest maps. Participants said Census maps should be more up to date and follow these other models. One novice participant went so far as to say the Census maps looked “archaic.”

Some experts struggled with being able to identify different parts of the county, not seeing or understanding how to use the different icons of the map, such as the identify icon, or the select icon. As well, two experts opted to right click and save the image that way as they did not know how to download the map in any other way that would keep the image as a map (i.e., they missed or did not understand the “download as pdf” option).

Figure 10: Reference map of Fairfax, VA from AFF site, using the Reference Map option from the left navigation.

Figure 11: Reference map of Fairfax, VA from AFF site, using the FactSheet option.

Recommendation: Keep maps updated to reflect what users expect from maps, given their experience with Google maps, GPS and map Web sites, such as Mapquest.com. We agree with our participants who said that our maps look old and outdated and reflect poorly on the Census Bureau. Tweaks to the current maps could include a sharper visual contrast for foreground text than is currently displayed. Include an option to select a specific city without needing the zip code.

Team Response: The colors in this system are limited to 256 different colors. The new AFF will not have this limit, and the maps will look different from the current maps. Users will be able to type in an address or geography, and as they move over a map, that area will highlight. There will be base maps that have minimal boundaries and features for users, but not so much information that it is cluttered. The navigation will feel more like modern maps, such as Google; users will be able to draw a box or circle around an area and see all points within that area.

3.5.1b Medium Priority Issues

3. Information in the center of the Main page is not used. Most participants did not attend to or use the links and information in the center of the main page. During debriefing, when asked about this area, some participants said that they thought it looked too confusing. There is currently a lot of white space on the right side of the page that is not being used at all. See Figure 12.

Figure 12: Screen shot of the American FactFinder Main page and the center area that was not attended to by novice users.

Recommendation: Make better use of the space on the page. Use more white space in the center of the page to organize the center information. Use less white space on the right side of the page: expand the information so that it stretches to the right.

Team Response: The new design is completely different and does not have this area on the main page.

4. Census jargon is used throughout the Web site. Normally, this is a recurring, high-priority issue in the Usability Lab’s evaluations of Web sites (see Romano-Bergstrom, Chen & Holland, 2011). However, this usability study, few participants commented on Census jargon. The participants that did comment said confusing words included: NAICS, SHP, ASM, GS, data revision notices, 2004 value and 2004 percent share.

Recommendation: Eliminate Census jargon and use words that are typical for novice users. At the very least, define acronyms and unfamiliar terminology.

5. The “Data Sets” pathway forces expert users down a particular, somewhat rigid path. If the expert user makes a choice that does not lead them to the content they were after, the user must back out and start all over which can be time consuming and frustrating.

Expert users did not always know which data table/product would contain the information they needed. Users could choose from many different table types within the data sets tab, such as custom table, detailed tables, subject tables, etc. and once the user selected one of the tables then they were prompted to enter additional geographical information before seeing what content was in the table. This led to many instances where expert users wasted time going through all the steps to load a particular table only to find that it was not the table they needed. Participants would then have to back out, choose a different table type and then go through the whole process again to add back in their specific geographic interest to check if this new table would have the content they were after. For some tasks, this procedure was repeated more than three or four times before the user was satisfied with the table. Each time they had to add back in the geography which was time consuming and, users said, frustrating.

Recommendation: Allow users to access the data tables without needing to know what data set or specific table it comes from. Allow users to specify the topic they are interested in regardless of whether they have identified their geographical level or not. Allow users to verify that the content displayed is in fact the content they are after, before the user has to make additional steps, such as identifying the geographical level.

6. Many of the expert participants were often expert in either the Demographic or the Economic content, not, typically, with both.

If the expert user was not familiar with economic data, for example, they would struggle more with finding the content they were after. Experts who were not familiar with the economic data made sure to mention that they did not use the economic data in their work and thus were not familiar with

How the interface worked

What the differences were in the data products, or

Which data product to choose

Recommendation: Make it easier for a user to choose the content they are after rather than first having them know which data set the content resides in. For example, do not require the user to know what content would be in the Economic Census area, versus what content would be found in the County Business Patterns area.

7. Experts did not use the various AFF functionalities, opting instead for the familiarity of what they knew, such as .xls

If the expert participant had not done something with the AFF interface before, such as changing the data class, moving the rows in a table around, or saving and reloading the data table, it was not immediately obvious how the user was supposed to do it. Most users reported that instead of working within the AFF window, they would typically download the content to an .xls spreadsheet and manipulate the data there. A few experts were able to eventually figure out how to change a data class on a map, but this was not the case for all users.

Recommendation: It appears that most expert users prefer to download the maps in a more common format (such as .xls) which they are familiar with and can use on their own time. Allow users to continue to download content. Also if some of the functionality of the new AFF involves manipulating the data with the AFF tool, consider this a lower priority as users may ignore this capability and opt to download the data rather than learn a new feature or online tool when the one they know (e.g., .xls) works. For functionality that a user would not be able to do in xls, such as changing the data class on a map, make sure to have useable instructions on how to use a particular tool.

3.5.1c Low Priority: Issues

8. The top navigation was seldom used. This type of finding is usually a high-priority issue (Romano Bergstrom et al., 2011) because the top navigation bar is often critical to the user’s success in finding target information. However, on the AFF Web site, the links on the top navigation were not useful to participants. During debriefing, when asked about the top navigation, participants commented that, aside from the Search feature, they did not use it. Rather, participants tended to use the left navigation the most. See Figure 13 for a screen shot that highlights the top navigation.

Figure 13: Top navigations on the Baseline AFF Web site.

Perhaps our task questions, aside from when users went into search, were not answerable by the top navigation links. These links are certainly secondary to the main topic-based navigation (on the left) that most users tried. So the top navigation links (Main, Feedback, FAQs, Glossary, Site Map, and Help) were not relevant to the participants in this study. However, because we were not asking task-based questions that required users to click on some of the links at the top in order to find what they were looking for, when participants did not click up there, it did not matter, and thus the finding is given a low priority. Future studies should include task questions targeting some of the top navigation links, if the task is representative of what users come to the site to do.

Recommendation: Move items that are seldom used, such as “Feedback” and “Site Map,” from the top navigation to a more subtle location, such as the bottom navigation. Remove FAQs, since they are also located on the bottom of the screen, and it is redundant to have them on the screen twice. Also, include a link to American FactFinder-relevant FAQs on the Help screen, since people who are looking at FAQs are seeking help. Add links to the top navigation that are useful to users, such as adding a link for maps or data. These would provide users with alternate routes of finding important and frequently sought information.

Other User Feedback

Participants said they found it puzzling that information about Puerto Rico was so prominent on the Main page. One participant recommended moving it below the fold of the page. Another recommended that it be placed in the Archived data.

A few participants commented that there did not need to be so many pictures on the Main page.

A number of experts mentioned that they wanted the Advance Query restored.

Many experts immediately accessed the data through the Data Sets link in the lower left -hand navigation column.

3.5.2 2011 Follow-Up Study

3.5.2a High-Priority Issues

Testing identified a number of high-priority usability issues in the 2011 Follow-Up study.

9. Using the geography overlay was overly complex and confusing. Participants did not understand how to get a specific geography (e.g., Maryland) for a topic they were interested in. This contributed to participants not finding the information they were looking for.

Participants often experienced difficulties adding in geographies. For example, most users did not know that once they clicked on the state, they had added it to the “Your Selections” box. The lack of feedback caused participants to click on the state numerous times, but still they did not notice that the state had been added to their selections. Many participants tried to add their specific geography (e.g. Maryland) by either clicking on the blue link label or checking the box. One participant said, after clicking the check box and clicking on the Add button, “I’m trying to see if it changed anything.” The participant did not notice that her state had been added. One participant said, “It says it was added to my selections but I don’t know what that means.” One participant said, after opening the Geographies overlay, “I know I want to go here. But once I get here, I don’t know what to do.” Another participant said, after selecting 4 states of interest and then clicking Add, “I’m not sure where they went. Humm now I’m confused.” See Figure 14.

Participants did not understand that their search was being updated beneath the overlay. Users missed seeing that the results were underneath, even though the overlay is more opaque than in Iteration 39 testing and slightly moved down. These changes seem to have been too subtle. See Figure 15.

Figure 14: Screen shot of page after adding VA. Label “Virginia successfully added to Your Selections” was meaningless. Nothing appeared to have changed.

Figure 15: The geography overlay covered the main search results.

Participants search on anything related to their topic in the geography search box, including many other things in addition to geographies. They use the search field as a Google-like search, typically after the other searches on the site (“Quick Start” and “Search within Results for…”) failed to get them any information related to their search.) See more on this in issue # 11 below.

The geography filters section was confusing. None of the participants who ended up adding their geography to the “Your Geography Filters” understood what it was for. When participants do a search on a single geography in the Name search, the result appears in the “Your Geography Filters” but this is not what participants are expecting. Participants said they were expecting to get data about the geography that they had just searched on. The “getting data” box appears after the participant has searched and this implies that the geography overlay will include data. See Figure 16. Participants said that they were expecting to get some type of information about Maryland (after typing Maryland into the Name search). After Maryland appeared in “Your Geography Filters” participants were confused and said they got nothing.

Note: The population overlay works much the same way as the geographic overlay in that it hides the data beneath the overlay. Participants who opened the population overlay also missed that the data was updating beneath the overlay. Thus any fix to the geography overlay would also be relevant to the population overlay.

Figure 16: The “getting data” implies the search is getting data.

Discussion: These problems with the geography are similar to what participants experienced in Iteration 3 testing. Thus we can see that the fixes the design team implemented did not go far enough. The overlay (though more opaque and slightly moved down) is still covering most of the results. One fix that was demonstrated to the team was a slow motion action of the geography being loaded into the “your selections” box. The team thought that this might work to both show users what their action of loading a geography was, as well as highlighting to users where the “your selections” was located and how that area was connected to their geography search. During 2011 Follow-Up testing the feature, we were told, was working, but it worked so quickly that no participant saw the movement.

Recommendation: Simply the geography overlay. Make it apparent that when a participant clicks on a state (or other geo level) that something has happened, and that the content now will all be about their specific geography.

We recommend doing some low-fidelity testing focusing on the geography interface. We could have a few different alternate versions mocked-up and then see which one works better for most participants. Some suggested alternate geography interfaces:

Add a button to the "Your Geography Filters" that says "Add Search Term". When you click the button it takes whatever is in the geography filters and places it in "Your Selections" and closes the Geography window.

Put the complexities of the geography tool, even the “Your Geography Filters” section deeper in the interface, (a few clicks in), or as a tab on the interface so that most general users who do not need obscure geographies do not get lost with the overly complex interface.

Have the “Your Selections” always in view so that once the geography has been added, it is clear that this has happened. Slow down the animation that was demonstrated to the team so that users will see it. Once the animation is slower, have the chosen geography move all the way into the “Your Selections” box, not to some location above the fold (if the participant happens to be scrolled down on the page).

Move the "Your Selections" box to where the “Your Geography Filters” box is currently. And have a Step 1) Choose your geography (state, county ,etc.)

Step 2). Click Get ResultsAdd a button to the "Your Geography Filters" that says "Add Search Term". When you click the button, have it take whatever is in the geography filters, place it in "Your Selections" and close the geography window.

Team Response to user issues with overlays10: As part of the on going design process, IBM is making an effort to minimize the use of overlays. IBM will also explore the feasibility of allowing users to reposition overlays, though allowing the user to move an overlay then requires them to manage the placement of the overlay, which could present another set of usability challenges. Closing or minimizing the overlay when the user clicks anywhere outside the overlay is a common web UI interaction, which IBM will explore the feasibility of implementing.

10. Participants don’t understand the “Your Selections” area. Some participants did not see that their search terms were in the “Your Selections” area, other participants did notice their search terms were there but did not understand how it was related to the rest of the site. Consequently, most participants were not able to understand the main functionality of the site.

One user tried to click on labels in the “Your Selection” area—while he did notice the “Search Results” area, he did not understand how they were connected to what he was searching on. When he was asked at the end of the session what he was trying to do when he clicked on an item in the “Your Selection” area, he said that he was trying to see if it would take him to data. What was listed in the “Search Results” area was not relevant to what he had searched on, so instead he thought he needed to work within the “Your Selections” area because that at least had terms that he understood. It is likely that he was led to believe that the “Your Selections” area was where the results would appear because that was the only area that had relevant terminology (the terms he had searched on). All the links in the “Search Results” area were too confusing and often NOT related to his search query. See more on issues with label names in Finding # 13 below.