SOP Data Collection Project -- SSA Template 081012

SOP Data Collection Project -- SSA Template 081012.doc

Formative Data Collections for Informing Policy Research

SOP Data Collection Project -- SSA Template 081012

OMB: 0970-0356

Street Outreach Program Data Collection Project

OMB Information Collection Request- Formative Generic Clearance

0970 - 0356

Supporting Statement

Part A

August 2012

Submitted By:

Caryn Blitz, Ph.D.

Office of the Commissioner

Administration on Children, Youth and Families

Administration for Children and Families

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

1250 Maryland Avenue, SW, 8th Floor

Washington, DC 20024

A1. Necessity for the Data Collection

Currently, the only data reported to the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) from their Street Outreach Program (SOP) grantees consist of four data elements reported through FYSB’s Runaway and Homeless Youth Management Information System: 1) number of contacts made by SOP staff with youth either on the street or in drop-in centers; 2) number of youth contacts that were sheltered at least one night; 3) total number of materials distributed by staff to youth on the street – written materials, health and hygiene products, and food and drink items; and 4) basic demographic information. Further information is needed to document current service utilization and service utilization needs, as well as the issues and issues and problems experienced by homeless street youth at each of 11 SOP grantee sites that will be involved in this data collection.

A2. Purpose of Survey and Data Collection Procedures

A2.1 Purpose

The purpose of the Street Outreach Program (SOP) Data Collection Project is to obtain information on service utilization and needs from a subset of homeless street youth being served by FYSB’s SOP grantees. The goal is to learn about street youths’ needs from their perspective, to better understand which services youth find helpful/not helpful, and/or alternative services they feel could be useful to them. The information collected will be used for internal purposes only and will not be released to the public

A2.2 Data Collection Procedures

A2.2a Description of Respondents

The respondents that will provide feedback will be street youth served by FYSB’s SOP grantees as well as street youth who do not currently utilize services from SOP grantees in each city. The eleven cities include: Austin, TX; Boston, MA; Chicago, IL; Washington, DC; Minneapolis, MN; New York City, NY; Omaha, NE; Port St. Lucie, FL; San Diego, CA; Seattle, WA; and Tucson, AZ. The youth served by these programs are between 14-21 years of age and are homeless. These homeless youth may use SOP drop-in centers to take a shower, eat a hot meal or obtain food coupons, received hygiene kits, and/or obtain referrals for medical, dental, mental health or social services. The youth who do not use SOP services are included as respondents to try and identify whether they have needs that the SOP grantees are not currently able to meet. This information will help SOP grantees to improve their services and better meet the needs of all homeless street youth in their city.

A2.2b Sampling Design and Recruitment

Data will be collected via focus groups and computer-assisted personal interviews. All data will be collected in person.

Personal Interview: An unbiased method for sampling the homeless has not been identified. Many studies have clearly documented the difficulty associated with any attempt to enumerate homeless populations (e.g., Bur & Taeuber, 1991; Dennis, 1991; Rossi, Wright, Fisher, & Willis, 1987; Wright & Devine, 1992). A promising method, the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) approach (Heckathorn, 2002; Heckathorn et al., 2002) has been used with adult and youth homeless populations (Coryn et al, 2007; Gwadz et al., 2010) and with small native communities in the Arctic (Dombrowski et al., in press).

Local research staff will recruit initial “seed” respondents by word of mouth and by handing out and posting the Interview Recruitment Brochure (Attachment A) in locations frequented by street youth. To assure the highest degree of coverage among youth, two initial seeds will be identified in each city. Once selected, a set of screening protocols that are asked before the bulk of the interview questions begin (see Attachment B: Interview Questions) will be used to verify that the initial seeds meet the study age range and definition for being homeless, and are screened out for the following: inebriated or high, cognitively impaired, or actively psychotic. To be eligible to participate in the study, individuals must be 14-21 years of age and meet the definition of “homeless” that best describes their age group. This study will employ the Stewart A. McKinney Act of 1987 definition if homeless for individuals over the age of 18: An individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, or an individual who has a primary nighttimes resident that is a) a supervised publicly or privately owned shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (including welfare hotels, congregate shelters, and transitional housing; or b) a public or private place not designated for or ordinarily used as regular sleeping accommodations for human beings (HUD, 1995). For those participants 18 years of age or younger (to age 14), the study will employ the definition of “homeless” provided by the National Network of Runaway and Youth Services: defined as someone 18 years or younger who cannot return home or has chosen never to return home and has no permanent residence (GAO, 1989).

Initial seed respondents will be provided with a $20 gift card for their interview and will be offered additional gift card to recruit people from their social networks to participate in the interview. Each seed will be given three coupons (see Attachment C: Seed Coupon) to give to homeless youth they know. Coupons will have unique identifiers that will link them to their seed. Coupons will have an expiration date of 7-14 days to allow for tracking the rate of return and to reduce respondent burden. Initial seed respondents will be provided a $10 gift card for each returned coupon that results in a completed interview. Thus, a respondent who completes the interview and successfully recruits three peers would receive $50 total. Each new participant will be offered the same number of coupons and incentives to recruit respondents from their social networks, up to the fourth seed.

Figure 1 (see below) is a visual respresentation of how the reimbursements will operate within the RDS design. Solid-colored circles represent homeless individuals who have completed a personal interview. Arrows indicate the recruitment coupons given to peers. Bold arrows signify that an individual was successfully recruited and completed a personal interview. Therefore, each bold arrow indicates a $10 gift card for the recruiter. Thin arrows that lead to circles marked with an “X” indicate that the coupon was not returned and the seed was unsuccessful.

Two seed respondents will be identified in each city. Previous work conducted by Dombrowski with indigenous populations in Canada has demonstration that about half of all initial seeds do not start network trees (see Figure 1, Seed 2) and for every three coupons given to a respondent, only 1.1-1.4 were returned for successful interviews.

Given the contractor’s previous success in recruiting and interviewing homeless adolescents and women, they anticipate that for every three coupons given, two successful interviews will be achieved. An example of a successful seed can be seen in Figure 1, Seed 1. Based on Heckathorn’s analyses, “previous applications of RDS showed that the number of waves required for the sample to reach equilibrium is not large, generally not more than four to six” (Heckathorn et al., 2002, p. 58). Equilibrium indicates that further iterations are unlikely to change the demographics of the samples (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004; Salganik, 2006). Based on these assumptions, it is estimated that each seed that is successfully initiated will result in 31 interviews by the 4th recruitment wave for a sample of 62 homeless street youth in each city. To account for seeds that never initiate, a third seed will be selected in cities for which half the sample has not been identified seven weeks after the data collection begins. Based on the work by Dombrowski, coupons should only be redeemed in person at the SOP agency. Prior experience suggests that some level of inconvenience is needed for respondents to recruit “closer” network members they believe will actually participate, increasing their odds for reimbursement. Without his level of involvement, it is difficult to saturate personal networks and draw conclusions about the representativeness of the sample. Recruitment and interviews will take place over a 5 month period.

Focus groups: A convenience sample will be used for the focus groups. SOP agency staff will recruit focus group participants (see Attachment D: Focus Group Recruitment Brochure, Attachment E: Focus Group Consent, and Attachment F: Focus Group Questions). Three focus groups of six participants each will be conducted at each of the 11 sites.

A3. Improved Information Technology to Reduce Burden

Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI) will be employed using netbooks. General questions will be administered by trained interviewers. Respondents will answer more sensitive questions directly on the netbooks. This methodology reduces burden by saving time for both the interviewer and the respondent by providing a streamline interview that includes screening questions and automatic skip patterns. The netbooks are highly mobile and can be transported anywhere for administration of the interview. The netbook interview and technology also eliminate the need for paper forms, data coding, and data entry; data are downloaded to the contractor’s secure server. Finally, the netbooks are password protected, thus ensuring the safety and security of the data.

A4. Efforts to Identify Duplication

As mentioned in A.1, only a few, limited pieces of data on aggregate provision of service per SOP grantee is currently available. While FYSB has more detailed information on homeless youth in its Basic Centers Program (BCP) and Transitional Living Program (TLP), the youth in those programs – younger and still connected to families for BCP, older and able to tolerate the structure and rules of a TLP – are qualitatively different from the youth who are served by the SOP. The few studies conducted nationally on street youth indicate that are the most vulnerable, difficult to reach, chronically homeless, and in need mental, physical and behavioral health services. Information from the point of view of youth being served by SOP grantees is needed to improve services and outreach to street youth.

A5. Involvement of Small Organizations

Eleven SOP grantees will be involved in data collection. Data collection processes have been streamlined to reduce administrative burden. The interview will be programmed and loaded onto hand-held computer netbooks for ease of administration. The programmed interview includes screening questions and automatic skip patterns to avoid unnecessary questions. Issues of data coding and data entry are eliminated by using the CAPI technology, thus reducing burden, as SOP grantee staff can easily download interview data electronically to the contractor’s secure server. Focus groups will be recorded, with recordings electronically downloaded to the contractor’s secure server and collected and transcribed by the contractor.

A6. Consequences of Less Frequent Data Collection

This is a one time data collection.

A7. Special Circumstances

There are no special circumstances for the proposed data collection efforts.

A8. Federal Register Notice and Consultation

In accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (Pub. L. 104-13) and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) regulations at 5 CFR Part 1320 (60 FR 44978, August 29, 1995), ACF published a notice in the Federal Register announcing the agency’s intention to request an OMB review of this information collection activity. The first Federal Register notice to renew ACF’s generic clearance for pretesting was published in the Federal Register on June 10, 2011 (vol. 76, no. 112, p. 34077), inviting public comment on our plans to submit this request. ACF received no comments or questions in response to this notice.

The second Federal Register notice was published in the Federal Register on August 29, 2011 (vol.76, no. 167, p. 53682.

A9. Payment of Respondents

As discussed above in section A2., respondents will be provided $20 per CAPI, $20 per focus group, and an additional $10 (up to $30) for each new respondent that a participant recruits (i.e., up to 3 new respondents), as a token of appreciation.

Justification: Monetary incentives are widely used in community-based physical and mental health research. One concern is that monetary incentives represent an unnecessary allocation of scarce monetary resources. From a methodological standpoint, however, monetary incentives are well justified if they increase participant response rates and thus allow for the collection of important information that might otherwise go undetected (Ensign, 2005). From an ethical standpoint, the most central concern is that monetary incentives can coerce individuals into taking risks that they otherwise would not take. This is especially true for low-income and homeless individuals who may lack the resources necessary to meet basic physical and psychological needs. These concerns are most relevant to medical studies in which, for example, the efficacy of a new medication or medical treatment is being examined. It has been found, however, that such concerns are of little relevance to minimally invasive procedures that carry little or no risk, such as personal interviews or focus groups in which individual opinions, attitudes or behaviors (e.g., service utilization) are of interest. This conclusion was reached by Grant & Sugarman (2004) as part of the discussion of the ethical concerns with monetary incentives for the American Psychological Association’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct.

Another important concern, related both to the allocation of resources and ethical practices, is the determination of an appropriate incentive amount. In discussing this issue in relation to ethical practices, Dickert and Grady (1999) reviewed several payment models, and concluded that a “wage-payment” approach maintains the integrity of widely accepted scientific ethical codes. In the wage-payment approach, participation in research studies is conceptualized as a form of employment. They argue that participation in research studies require minimal skills and may thus be viewed as a low-skill job.

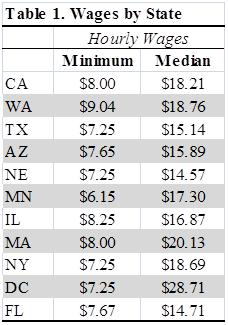

I n

order to determine the appropriate amount to offer respondents, data

regarding the minimum and median wages in each of the study states

was gathered from the US Department of Labor (DOL; 2012).

n

order to determine the appropriate amount to offer respondents, data

regarding the minimum and median wages in each of the study states

was gathered from the US Department of Labor (DOL; 2012).

This information is reported in Table 1. The process of obtaining informed consent (with signed consent forms; see Attachment G: Interview Consent Form–Seed and Attachment H: Interview Consent Form–Non-Seed) and participation in the computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) will require approximately 1.25 hours of the respondent’s time. Respondents will be allowed to take a 10-15 minute break during the interview if they choose. The process of obtaining informed consent (with signed consent forms) and focus group participation will require approximately 1.5 hours of the respondent’s time. Combined with the DOL information on hourly wages and opportunity costs (Ensign, 2003), we determined that $20 per hour each for CAPIs and focus group participation represents both a fair and ethical amount. This amount allows participants to be compensated for their time and effort while not being large enough to raise any concerns regarding coercion. We will provide gift cards in order to eliminate the possibility of the reimbursement being used to purchase ethically unjustifiable items (e.g., drugs; see Ensign, 2003, for the use of this approach). The gift cards will be purchased from stores that sell grocery items, hygiene products, and clothing, but not alcohol or tobacco.

The sampling design of this project utilizes Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS), which requires that participants are reimbursed for recruiting others. Each seed will be given three coupons (Attachment C) to give to homeless youth that they know. Coupons will have unique identifiers that will link them to their seed. Coupons will also have an expiration date of 7-14 days to track the rate of return. Seed respondents will be provided a $10 gift card for each returned coupon that results in a completed interview for their recruitment effort. It is estimated that it will take each seed approximately one hour to successfully recruit another respondent and collect their gift card (corresponding with an hourly wage of approximately $10 per hour). Thus, a respondent who completes the interview and successfully recruits three peers would receive $50 total. Each new participant will be offered the same number of coupons and gift cards to recruit respondents from their social networks, up unto the fourth seed.

A10. Confidentiality of Respondents

The data collection will employ Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) techniques for the personal interviews. Interviews will be conducted on netbooks programmed with Voxco software and set to upload directly to the contractor’s secure server. Data stored on the computers will be only identified by Random ID number and will be encrypted to protect respondents’ identities. The CAPIs will be audio recorded for transcription of open-ended data using audacity (a free open-source software program). The audio files will be password protected and will not contain any identifying information. These audio files will be programmed to be uploaded to the contractor’s secure server with the CAPI interview file. Respondents will only be identified on the CAPI program by Random ID. Random ID numbers will also be assigned to RDS coupons, allowing for linkage of social network trees.

The focus groups will also be audio recorded (using Olympus digital recorders). Each SOP grantee will receive a recorder, which will be sent to the contractor upon the completion of all three focus groups. The audio files will be downloaded to the contractor’s secure server.

All audio files will be transcribed by staff hired by the contractor and will complete required training and sign a confidentiality agreement before beginning work on the transcriptions. Typed transcripts will be de-identified and saved on the contractor’s secure server. Only project staff will have access to the typed transcripts. Audio files will be kept for one year after the completion of the project in order to allow project staff to respond to any questions that may arise from SOP grantees or FYSB staff. Contract staff will have a list of pre-arranged random ID numbers to assign to focus group participants and will indicate when those random numbers have been used.

Only contract staff will have access to the files that will link the respondents to their answers. All private information will be kept separate for the duration of the project. Respondents will be informed that their information will be kept private to the extent permitted by law.

A11. Sensitive Questions

The majority of the interview content is non-invasive. For example, most questions deal with opinions associated with service use and agency programs. Some demographic information is collected to give street outreach agencies a better understanding of their clients. The interview does include screening questions to rule out youth that are inebriated or high, cognitively impaired, or actively psychotic, and a brief section in the interview asks questions about past sexual activity, STI's, substance use, and mental health and criminal behavior (see Attachment B: Interview Questions). Respondents will be informed that their information will be kept private to the extent permitted by law and that their participation is voluntary. They may choose to not answer a question and can move on to the next one. These questions have been implemented by the contractor previously in other homeless youth studies and are commonly asked in surveys of homeless youth in order to understand the extent of their problems and service needs.

Runaway and homeless youth experience emotional and physical trauma that they carry with them onto the streets. Two decades of research on runaway and homeless adolescents make it very clear that the vast majority run from or drift out of disorganized families. Several studies have documented problems in the caretaker-child relationship ranging from control group studies of bonding, attachment, and parental care (Daddis, Braddock, Cuers, Elliot, & Kelly, 1993; Schweitzer, Hier, & Terry, 1994; Votta & Manion, 2003) to caretaker and runaway child reports on parenting behaviors and mutual violence (Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Ackley, 1997). There have been numerous studies based on adolescent self-reports that indicate high levels of physical and sexual abuse among chronic runaways and homeless youth perpetrated by caretakers (Farber, Kinast, McCoard, & Falkner, 1984; Janus, Archambault, Brown, & Welsh, 1995; Janus, Burgess, & McCormack, 1987; Kaufman & Widom, 1999; Kennedy, 1991; Kufeldt & Nimmo, 1987; Kurtz, Kurtz, & Jarvis, 1991; Molnar, Shade, Kral, Booth, & Watters, 1998; Mounier & Andujo, 2003; Noell, Rohde, Seeley, & Ochs, 2001; Pennridge et al., 1990; Rotheram-Borus, Mahler, Koopman, & Langabeer, 1996; Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe, & Hoyt, 2000; Tyler, Hoyt, Whitbeck, & Cauce, 2001; Tyler, Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Cauce, 2004; Whitbeck and Hoyt, 1999; Whitbeck & Simons, 1993, p.6).

Homeless youth may also be arrested or taken into police custody for other acts committed while away from the home, including violation of probation, burglary, drug use, or drug dealing. Researchers emphasize that criminal offenses or illegal acts committed by runaways frequently are motivated by basic survival needs, such as food and shelter; the presence of adverse situations, such as hunger and unemployment; self-medication through use of alcohol and drugs; and a lack of opportunities for legitimate self-support (Kaufman & Widom, 1999; McCarthy & Hagan, 2001; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Additionally, while running away can increase the odds of the youth engaging in delinquent or criminal behavior, it can also increase the odds of the youth being exposed to or becoming the victim of criminal or delinquent acts (Hammer et al., 2002; Hoyt, Ryan, & Cauce, 1999). For example, it was found by Hoyt and colleagues (1999) that the amount of time homeless adolescents spent living on the streets, as well as prior experience of personal assault, was associated with increased risk of criminal victimization.

Finally, homeless young people living on the street tend to be very involved in ‘street’ networks and culture. Their primary communities are comprised of other street-involved young people who get most, if not all, of their needs met through engaging in the street economy, such as eating at soup kitchens, sleeping outdoors, and spare-changing/begging for money (Thompson et al., 2006) due to estrangement from their families and lack of desire on their part and/or their families to reconnect. It has been shown that acculturation to the streets and street economy progresses with the length of exposure to homelessness and homeless peers (Auerswald & Eyre, 2002; Gaetz, 2004; Kidd, 2003; Kipke et al., 1997). ‘The length of time the individual is homeless and on the street suggests that homelessness is dangerously close to becoming a way of life for some young people’ (Reid & Klee, 1999, p. 24).

A growing body of research demonstrates the need for services among this highly vulnerable population. Without social service intervention, there is an increased likelihood of repeated exposure to trauma and victimization (Gaetz, 2004; Kipke et al., 1997; Thompson, 2006; Tyler et al., 2001; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Thus, agencies providing services to homeless individuals must identify the extent of their needs and adopt a proactive approach by contacting and offering assistance to homeless street youth, and, if possible, early in their homeless experience before they become entrenched in street culture (Reid & Klee, 1999).

A12. Estimation of Information Collection Burden

Instrument |

Annual Number of Respondents |

Number of Responses Per Respondent |

Average Burden Hours Per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage |

Total Annual Cost |

Focus Groups |

198 |

1 |

1.25 |

247.50 |

$13.33 |

$3,291.75 |

Computer- Assisted Personal Interviews |

682 |

1 |

1.25 |

852.50 |

$13.33 |

$11,338.25 |

Estimated Annual Burden Sub-total |

1,100 |

|

$14,630.00 |

|||

A13. Cost Burden to Respondents or Record Keepers

There are no additional costs to respondents or recordkeepers

A14. Estimate of Cost to the Federal Government

The average annualized cost to the Federal government is $275,000.

A15. Change in Burden

This is an additional collection under the formative generic clearance.

A16. Plan and Time Schedule for Information Collection, Tabulation and Publication

The information that is collected will be for internal use only. Data collection is scheduled to occur over a six month period, including one month for pilot testing the RDS method and the CAPIs.

A17. Reasons Not to Display OMB Expiration Date

All instruments will display the expiration date for OMB approval.

A18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions

No exceptions are necessary for this information collection.

| File Type | application/msword |

| File Title | OPRE OMB Clearance Manual |

| Author | DHHS |

| Last Modified By | Molly Buck |

| File Modified | 2012-08-13 |

| File Created | 2012-08-10 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy