2402ss03

2402ss03.doc

Willingness to Pay Survey for Section 316(b) Existing Facilities Cooling Water Intake Structures

OMB: 2040-0283

Supporting Statement for Information Collection Request for

Willingness to Pay Survey for §316(b) Existing Facilities Cooling Water Intake Structures: Instrument, Pre-test, and Implementation

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART A OF THE SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1

1. Identification of the Information Collection 1

1(a) Title of the Information Collection 1

1(b) Short Characterization (Abstract) 1

2. Need For and Use of the Collection 4

2(a) Need/Authority for the Collection 4

2(b) Practical Utility/Users of the Data 4

3. Non-duplication, Consultations, and Other Collection Criteria 5

3(b) Public Notice Required Prior to ICR Submission to OMB 6

3(d) Effects of Less Frequent Collection 12

4. The Respondents and the Information Requested 12

(I) Data items, including recordkeeping requirements 14

5(b) Collection Methodology and Information Management 19

5(c) Small Entity Flexibility 20

6. Estimating Respondent Burden and Cost of Collection 21

6(a) Estimating Respondent Burden 21

6(b) Estimating Respondent Costs 21

6(c) Estimating Agency Burden and Costs 21

6(d) Respondent Universe and Total Burden Costs 23

6(e) Bottom Line Burden Hours and Costs 23

6(f) Reasons for Change in Burden 24

PART B OF THE SUPPORTING STATEMENT 25

1. Survey Objectives, Key Variables, and Other Preliminaries 25

2(a) Target Population and Coverage 27

(III) Stratification Variables 27

2(c) Precision Requirements 29

3. Pretests and Pilot Tests 33

4. Collection Methods and Follow-up 35

4(b) Survey Response and Follow-up 35

5. Analyzing and Reporting Survey Results 36

ATTACHMENTS

Attachment 2: Full Text of National Stated Preference Survey Component 79

Attachment 3: First Federal Register Notice 99

Attachment 4: Second Federal Register Notice 109

Attachment 5: Description of Statistical Survey Design 116

Attachment 6: Preview Letter to Mail Survey Recipients 131

Attachment 7: Cover Letter to Mail Survey Recipients 132

Attachment 8: Post Card Reminder to Mail Survey Recipients 133

Attachment 9: Cover Letter to Recipients of the Second Survey Mailing 134

Engineering and Analysis Division 134

Attachment 10: Reminder Letter to Mail Survey Recipients 135

Attachment 11: Letter to Participants in the Telephone Non-response Survey 136

Attachment 12: Cover Letter to Recipients of the Priority Mail Non-response Questionnaire 137

Attachment 13: Priority Mail Non-response Questionnaire 138

Attachment 14: Telephone Non-response Screener Script 142

TABLES

Table A1: Geographic Stratification Design 13

Table A2: Schedule for Survey Implementation 20

Table A3: Total Estimated Bottom Line Burden and Cost Summary 23

Table B1: Number of Households and Household Sample for Each EPA Study Region 29

Table B2: Number of Non-responding Households in the Priority Mail and Telephone Subsamples 32

PART A OF THE SUPPORTING STATEMENT

1. Identification of the Information Collection

1(a) Title of the Information Collection

Willingness to Pay Survey for Section 316(b) Existing Facilities Cooling Water Intake Structures: Instrument, Pre-test, and Implementation

1(b) Short Characterization (Abstract)

On February 16, 2004, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) took final action on the Phase II rule governing cooling water intake structures at existing facilities that are point sources; that, as their primary activity, both generate and transmit electric power or generate electric power for sale to another entity for transmission; that use or propose to use cooling water intake structures with a total design intake flow of 50 MGD or more to withdraw cooling water from waters of the United States; and that use at least 25 percent of the withdrawn water exclusively for cooling purposes. See 69 FR 41576 (July 9, 2004). Industry and environmental stakeholders challenged the Phase II regulations. On judicial review, the Second Circuit (Riverkeeper, Inc. v. EPA, 475 F.3d 83, (2d Cir., 2007)) remanded several provisions of the Phase II rule. Some key provisions remanded are as follows: EPA improperly used a cost-benefit analysis as a criterion for determining Best Technology Available (BTA), and EPA inappropriately used ranges in setting performance expectations. In response, EPA suspended the Phase II regulation in July 2007 pending further rulemaking. The U.S. Supreme Court granted Entergy Corporation’s petition for writ of certiorari, solely on the question of whether EPA had the authority under §316(b) of the Clean Water Act to consider costs and benefits in decision-making. On April 1, 2009, the Court, in Entergy Corp. v. Riverkeeper Inc., decided that “EPA permissibly relied on cost-benefit analysis in setting the national performance standards … as part of the Phase II regulations.” EPA is now taking a voluntary remand of the rule, thus ending Second Circuit review.

On June 1, 2006, EPA promulgated the 316(b) Phase III Rule for existing manufacturers, small flow power plants (facilities that use cooling water intake structures with a total design intake flow of less than 50 MGD to withdraw cooling water from waters of the United States; and that use at least 25 percent of the withdrawn water exclusively for cooling purposes), and new offshore oil and gas facilities. Offshore oil and gas firms and environmental groups petitioned for judicial review, which was to occur in the Fifth Circuit, but was stayed pending the Supreme Court decision on the Phase II case. EPA has petitioned the Court for a voluntary remand of the existing facilities portion of the Phase III rulemaking. In developing the Phase III regulation, EPA began, but did not complete, a similar stated preference survey effort. The current effort builds on that earlier work.

EPA is now combining the two phases into one rulemaking covering all existing facilities. EPA will develop regulations to provide national performance standards for controlling impacts from existing cooling water intake structures (CWIS) under Section 316(b) of the Clean Water Act (CWA).

Under Executive Order 12866, EPA is required to estimate the potential benefits and costs to society for economically significant rules. To assess the public policy significance or importance of the ecological gains from the section 316(b) regulation for existing facilities, EPA requests approval from the Office of Management and Budget to conduct a stated preference survey. Data from the stated preference survey will be used to estimate the values (willingness to pay, or WTP) derived by households for changes related to the reduction of fish losses at CWIS, and to provide information to assist in the interpretation and validation of survey responses. As indicated in the prior literature (Cummings and Harrison 1995; Johnston et al. 2003a, 2005), it is virtually impossible to justify, theoretically, the decomposition of empirical estimates of use and non-use values. The survey will provide the flexibility, however, to estimate nonuser values, using various nonuser definitions drawn from responses to survey question 10. The structure of choice attribute questions will also allow the analysis to separate value components related to the most common sources of use values—effect on harvested recreational and commercial fish. In summary, the survey will provide estimates of total values (including use and nonuse), will allow estimates of value associated with specific choice attributes (following standard methods for choice experiments), and will also allow the flexibility to provide some insight into the relative importance of use versus non-use values in the 316(b) context.

Within rulemaking, among the most crucial concerns is the avoidance of benefit (or cost) double counting. Here, for example, the WTP estimates will include use and non-use values among a representative population sample. These may overlap—to a potentially substantial extent—with use value estimates that might be provided through some other methods, including revealed preference methods that might be used to estimate use values of recreational anglers for fish kill reductions (i.e., through related improvements in fishing quality). While using the proposed stated preference value estimates for benefit estimation, particular care will be given to avoid any possible double counting of values that might be derived from alternative valuation methods. In doing so, EPA will rely upon standard theoretical tools for non-market welfare analysis, as presented by authors including Freeman (2003) and Just et al. (2004). From a purely mechanistic perspective, survey results will be used to derive total values following standard practice for choice experiments (Adamowicz et al. 1998).

The target population for this stated preference survey is all individuals from continental U.S. households who are 18 years of age or older. The population of households will be stratified into four study regions: Northeast, Southeast, Inland, and Pacific. The Northeast survey region includes the North Atlantic and Mid Atlantic 316(b) benefits regions, the Southeast survey region includes the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico 316(b) benefits regions, the Pacific region includes states on the Pacific coast, and the Inland region includes all non-coastal states. In addition, EPA will administer a national version of the survey that does not require stratification. The sample of households in each region will be randomly selected from the U.S. Postal Service Delivery Sequence File (DSF), which covers over 97% of residences in the U.S. EPA intends to administer the mail survey to 7,628 households in order to achieve 2,288 completed responses assuming a 30% completion rate for selected households.

For the selection of households, the population of households in the 48 states and the District of Columbia will be stratified by the four study regions. The sample is allocated to each region in proportion to the total number of households in that region with the restriction that we get at least 288 completed responses in each region. A sample of 288 households completing the national survey version would be distributed among the study regions based on the percentage of regional survey sample to ensure that respondents to the national survey version are distributed across the continental U.S. Non-response bias has the potential to occur due to households failing to return a completed mail survey. EPA will use a combination of telephone and priority mailing to conduct a non-response study. EPA will analyze the characteristics of the completed and non-completed cases from the mail survey and non-response questionnaire to determine whether there is any evidence of significant non-response bias in the completed sample. This analysis will suggest whether any weighting or statistical adjustment is necessary to minimize the non-response bias in the completed sample.

As part of the testing of the survey instrument, EPA conducted a series 7 focus groups with 8-10 participants per focus group, with approval from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB control # 2090-0028). The Agency conducted focus groups in several regions to account for the potentially distinct information relevant to survey design. These focus groups were conducted following standard, accepted practices in the stated preference literature, as outlined by Mitchell and Carson (1989), Desvousges et al. (1984), Desvousges and Smith (1988) and Johnston et al. (1995). One of the focus groups incorporated individual cognitive interviews, as detailed by Kaplowicz et al. (2004). The focus groups and cognitive interviews allowed EPA to better understand the public's perceptions and attitudes concerning fishery resources, to frame and define survey questions, to pretest draft survey questions, to test for and reduce potential biases that may be associated with stated preference methodology, and to ensure that both researchers and respondents have similar interpretations of survey language and scenarios. In particular, cognitive interviews allowed for in-depth exploration of the cognitive processes used by respondents to answer survey questions, without the potential for interpersonal dynamics to sway respondents’ comments (Kaplowicz et al. 2004). Transcripts from these seven focus groups can be found in the docket for this ICR (ICR # 2402.01). EPA revised the survey based on the findings of the seven focus groups. These seven focus groups were conducted in addition to focus groups conducted previously by EPA under ICR #2155.01 to test the draft survey for the Phase III benefits analysis. Transcripts from the previously conducted focus groups for the Phase III analysis can be found in the docket for EPA ICR #2155.02 (Besedin et al., 2005). Findings from these previous focus groups were also incorporated into the development of the current survey.

The total national burden estimate for all components of the survey is 1,194 hours. The burden estimate is based on 2,288 respondents to the 7,628 mailed questionnaires and 600 respondents to the combined telephone and priority mail non-response survey. EPA assumes an average burden estimate of 30 minutes per mail survey respondent including the time necessary to complete and mail back the questionnaire and 5 minutes for each participant in the non-response survey. Given an average wage rate of $20.42, the total respondent cost is $24,381.

2. Need For and Use of the Collection

2(a) Need/Authority for the Collection

The project is being undertaken pursuant to section 104 of the Clean Water Act dealing with research. Section 104 of the Clean Water Act authorizes and directs the EPA Administrator to conduct research into a number of subject areas related to water quality, water pollution, and water pollution prevention and abatement. This section also authorizes the EPA Administrator to conduct research into methods of analyzing the costs and benefits of programs carried out under the Clean Water Act.

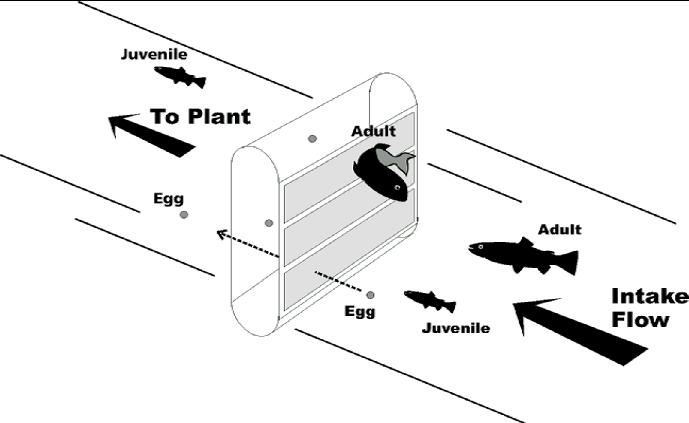

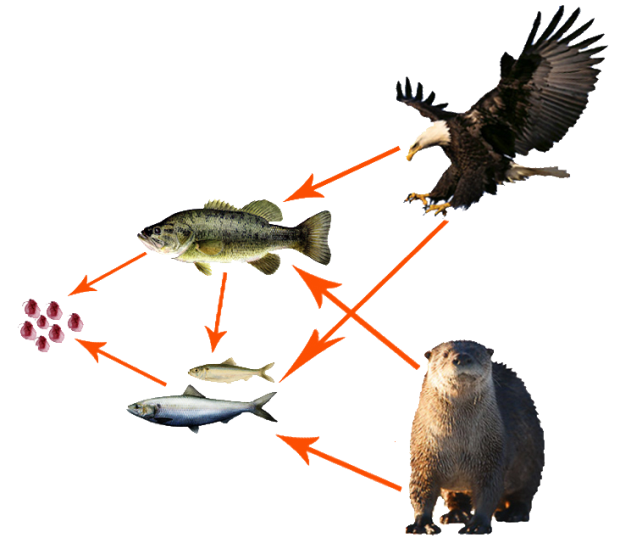

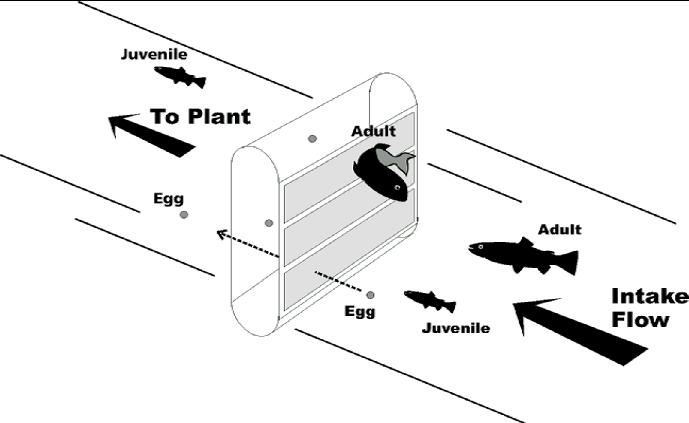

This project is exploring how public values for fishery resources are affected by fish losses from impingement and entrainment (I&E) mortality at cooling water intake structures. Understanding total public values for fishery resources, including the more difficult to estimate non-use values1, is necessary to determine the full range of benefits associated with reductions in I&E mortality losses, and whether the benefits of government action to reduce I&E mortality losses at existing facilities are commensurate with the costs of such actions. Because non-use values may be substantial, failure to recognize such values may lead to improper inferences regarding benefits and costs. The findings from this study will be used by EPA to improve estimates of the economic benefits of the section 316(b) regulation for existing facilities as required under Executive Order 12866.

2(b) Practical Utility/Users of the Data

EPA plans to use the results of the survey to improve estimates of the economic benefits of the section 316(b) regulation for existing facilities. Specifically, the Agency will use the survey results to estimate total values for preventing losses of fish through I&E mortality at CWIS, following standard practices outlined in the literature (Freeman 2003; Bennett and Blamey 2001; Louviere et al. 2000; U.S. EPA 2000).

3. Non-duplication, Consultations, and Other Collection Criteria

3(a) Non-duplication

There are many studies in the environmental economics literature that quantify benefits or willingness to pay (WTP) associated with various types of water quality and aquatic habitat changes. However, none of these studies allows the isolation of non-market WTP associated with quantified reductions in fish losses for forage fish. Most available studies estimate WTP for broader, and sometimes ambiguously defined, policies that simultaneously influence many different aspects of aquatic environmental quality and ecosystem services, but for which WTP associated with fish or aquatic life alone cannot be identified. Other studies provide benefit estimates associated with improvements in fish (or aquatic) habitat, but do not link this to well-defined and quantified changes in affected or supported organisms. Still other studies address willingness to pay for changes in charismatic or recreational species that have little relationship to the types of forage fish that are the vast majority of species affected by cooling water intake structures.

For example, choice experiment studies such as Hanley et al. (2006a, 2006b) and Morrison and Bennett (2004) estimate WTP for aquatic ecosystem changes that affect fish, but the effects on fish are quantified and valued solely in terms of the presence/absence of different types of fish species. This approach renders associated results unsuitable for 316(b) benefit estimation. Also, many of these studies were conducted outside the U.S. (e.g., the European Union or Australia), making their use for benefit transfer to a U.S. policy context more challenging.

Other studies have estimated the value of changes in catch rates or populations of select recreational and commercial species, charismatic species such as salmon, or changes in water quality that affect fish, but none have specifically valued changes in forage fish populations. For example, Olsen et al. (1991) conducted a survey of Pacific Northwest residents, including both anglers and non-anglers, to determine their WTP for doubling the size of the Columbia River Basin salmon and steelhead runs. EPA’s proposed survey approach differs from this study and others like it (such as Cameron and Huppert 1989) in that it would include respondents from various geographic regions in the United States and would provide values for the full range of forage, recreational, and commercial species affected by 316(b) regulations, instead of valuing a few recreational species in one specific geographical area.

Among available studies, the most closely related is Johnston et al. (2010), which estimates total willingness to pay (WTP) for multi-attribute aquatic ecosystem changes related to improvements in forage fish in Rhode Island. Unlike other studies, the choice experiment data of Johnston et al. (2010) allow estimation of WTP associated with quantified changes in forage fish (e.g., WTP per fish or percentage change in fish), holding other ecological effects constant. That is, unlike results provided by other studies in the literature, WTP estimates of Johnston et al. (2010) are not confounded with values for other changes including water quality, habitat, overall ecological condition, charisma of species, etc. In addition, the choice experiment of Johnston et al. (2010) addresses species such as alewife and blueback herring that are neither subject to recreational or commercial harvest in Rhode Island, nor are charismatic species. Hence, the species affected are a close analog to the forage fish affected in the 316(b) policy context.

Although the methods and data of Johnston et al. (2010) allow estimation of total values associated with specific improvements in forage and/or recreational fish, the policy context and scale of the survey prevent its direct use for analysis of national benefits of the 316(b) regulation. Specifically, Johnston et al. (2010) estimate Rhode Island residents’ preferences for the restoration of migratory fish passage over dams in the Pawtuxet and Wood-Pawcatuck watersheds. Hence, the case study is for a watershed-level policy with statewide welfare implications. In contrast, 316(b) policies would have nationwide implications, both on ecosystems and on affected facilities.

3(b) Public Notice Required Prior to ICR Submission to OMB

In accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act (44 U.S.C. 3501 et seq.), EPA published two notices in the Federal Register on July 21, 2010 and January 21, 2011, announcing that the survey questionnaire and sampling methodology were available for comment. Copies of the first Federal Register notice (74 FR 42438) and second Federal Register notice (76 FR 3883) are attached at the end of this document (See Attachments 3 and 4, respectively). EPA received a number of comments on the proposed information collection, which are summarized in the following paragraphs. Also see docket # EPA-HQ-OW-2010-0595. EPA considered relevant comments on the draft survey when developing the survey questionnaire and sampling methodology for the current survey for existing facilities.

Some commenters expressed concern that the draft survey questionnaire and sampling methodology would not provide accurate estimates of WTP. Some stated that the proposed stated preference survey would overestimate WTP to prevent fish losses. Another commenter argued the opposite: that the proposed contingent valuation survey is biased against protecting ecosystems, and will drastically undervalue non-use benefits. EPA agreed that certain details of the stated preference survey and supporting documentation for the July 21, 2010 and January 21, 2011 Federal Register notices required revision. EPA has revised the survey instrument and supporting documentation accordingly. Following OMB approval of the focus groups, EPA conducted seven focus groups (including one set of cognitive interviews) to pretest the draft survey materials, to test for and reduce potential biases that may be associated with stated preference methodology, and to ensure that both researchers and respondents have similar interpretations of survey language and scenarios. As a result of this extensive pre-testing, a number of revisions were made to the draft survey that significantly improved its reliability and reduced its potential for bias. Hence, many of the survey design elements on which commenters took issue have already been removed or changed. In many other instances, however, focus groups showed little cause for concern, suggesting that many of the speculative claims raised by commenters have little value to the population being surveyed. EPA also notes that number of focus groups and interviews conducted for this survey—and the draft survey tested in 2005-06—far exceeds the number conducted for most stated preference surveys found in the published literature.

EPA notes that the survey proposed in this ICR is different in many ways from the draft survey for the Phase III benefits analysis that was peer reviewed in 2005 (Versar 2006). While findings from pre-testing of the previous draft survey were considered when developing the present survey, the present survey has undergone various revisions based on additional analysis and the results of recent focus groups. Due to these differences, EPA notes that many of the peer review comments received on the Phase III draft survey are no longer relevant for the survey proposed in this ICR. The Agency, however, takes all peer review comments very seriously, and has accounted for these comments in all survey revisions and in the development of the present stated preference survey.

One commenter argued that in conducting the stated preference survey, EPA should use the willingness-to-accept (WTA) metric in place of or in addition to WTP. EPA notes that good practice guidelines for stated preference surveys almost universally indicate the use of WTP elicitation mechanisms over WTA elicitation mechanisms. This is due to the potential for biases in WTA stated preference surveys that can be ameliorated by the use of the WTP format. WTP is also considered to be the more conservative choice, but in most cases, the divergence between WTA and WTP, as predicted, by theory, should be very small. EPA follows standard practice in proposing a WTP format in order to avoid these biases, comply with guidance and practice in the stated preference literature, and ensure a conservative benefit estimate.

Some commenters argued that hypothetical bias in the survey questionnaire would inhibit respondent’s ability to provide meaningful survey responses. EPA agrees that hypothetical bias is an important concern with stated preference surveys—and has taken this very seriously in survey development and testing. EPA does not agree that this inhibits respondents or that the literature suggests that hypothetical bias is unavoidable; in fact, the published literature includes approaches to mitigate such biases. The Agency followed the published literature in designing mitigation strategies to eliminate or at a minimum reduce the potential for hypothetical bias. This includes explicitly designing the survey to maximize the consequentiality of choice experiment questions through direct linkages to proposed EPA regulatory efforts. Moreover, the survey explicitly incorporates elements such as certainty follow-up question to enable mitigation of any remaining hypothetical bias (Ready et al. 2010). Focus group and interview transcripts show that, when asked explicitly, respondents almost universally indicated that their answers to choice questions in the survey instrument would be identical if the same questions were encountered in a binding referendum. This indicates that there is little evidence of hypothetical bias within the draft survey.

A commenter argued that the respondents to the survey would be informed and conditioned based on the information included in the survey and that this would lead to the creation of preferences where none existed before. EPA believes that this result is entirely expected, and is consistent with the academic literature. The Agency emphasizes that the sensitivity of values (and behavior) to information is true of both market and non-market values (Bateman et al. 2002, p. 298), and in no way invalidates the proposed non-market values that would be estimated through the proposed stated preference approaches. It is common practice in such surveys to provide substantial information to survey respondents. The survey information was pretested extensively during the seven focus group sessions and EPA revised or removed informational elements which respondents found confusing or misleading.

Some commenters argued that the survey results will be unreliable because the survey questionnaire contains inaccurate statements and comparisons which overstate the resource impacts from baseline I&E mortality and the regulatory options presented in the survey. EPA recognizes the importance of accurately characterizing resource and regulatory impacts and notes that the survey is based on the best biological and engineering data available. Despite the general observation that I&E impacts are small compared to other effects, I&E has been shown to have measurable impacts on local fish populations and communities. Importantly, increases in fishery sustainability and fish population values presented in the survey instrument are small. Overall, the Agency rejects the claims from commenters, based largely on feedback from focus group participants, that impacts are misrepresented, and emphasizes that the survey is explicitly designed to provide respondents with an understanding of the proposed policies that is as accurate as possible given the best available ecological science.

Commenters also questioned whether survey respondents would have sufficient comprehension of the issues in order to provide meaningful responses to the survey’s valuation questions. EPA agrees that in order to receive meaningful responses, a stated preference survey should provide information to respondents about the hypothetical commodity so that they understand and accept it and can give meaningful answers to the valuation questions. Given the importance of commodity comprehension, EPA devoted considerable attention to comprehension of the hypothetical commodity and related issues (e.g., understanding of payment vehicle, understanding of the ecological scores) during the recent focus groups and cognitive interviews and focus groups conducted for the original version of the Phase III survey instrument in 2005. Focus groups participants showed no difficulty understanding the format of the payment vehicle and that selecting Options A or B would result in increased costs to their household. They also correctly understood this cost as ongoing.

In addition to the comments regarding the payment vehicle, commenters expressed concern regarding respondent comprehension of the ecological scores used in the survey. EPA emphasizes that the reaction and understanding of likely respondents, as opposed to experts, is crucial when testing the communication of ecological information in stated preference surveys. The survey has undergone substantial changes in the way it communicates ecological information based on the results of the seven focus group sessions. For example, in the revised survey, EPA provides more precise information regarding the definition of “young adult fish” on Page 4, which currently states: “After accounting for the number of eggs and larvae that would be expected to survive to adulthood, scientists estimate that the equivalent of about 1.1 billion young adult fish (the equivalent of one year old) are lost each year in Northeast coastal and fresh waters due to cooling water use.” Overall, focus group and interview participants’ statements implied different opinions about the importance of preventing fish losses versus increasing fish population or improving the condition of aquatic ecosystems. Also, there did not appear to be any confusion over the fact that scores of 100 for various attributes are generally unattainable through reductions in CWIS fish losses alone. One commenter argues that the stated preference survey fails to account for effects on a number of non-fish species as well as effects on threatened, endangered, and other protected species. In response to this comment, EPA agrees but notes that focus group respondents suggested that additions to the survey’s length should be avoided. Thus EPA will not be able to use these survey results to represent absolutely complete benefits estimation, but will be able to say that a potentially substantial category of benefits, non-use benefits, has been included. As is common in surveys, EPA has chosen to present policy scenarios in simplified form to facilitate respondent comprehension, and to encourage respondents to focus on the most important policy characteristics related to fish losses. Such simplification of the survey helps to balance the provision of detailed policy information against respondents’ cognitive abilities to consider a large number of attributes simultaneously (Louviere et al. 2000).

Some commenters stated that EPA did not sufficiently emphasize the uncertainty associated with effects and costs of the proposed policies presented within the survey. EPA agrees that there is uncertainty regarding the number of fish killed annually, as well as the effects and costs of the regulatory policies presented within the survey. Additionally, EPA does note uncertainty within the current existing facilities survey. For example, the following statements are included in the current survey version for the Northeast region: “Although scientists can predict the number of fish saved each year, the effect on fish populations is uncertain. This is because scientists do not know the total number of fish in Northeast waters and because many factors – such as cooling water use, fishing, pollution, and water temperature – affect fish populations”, and “Policy costs and effects depend on many factors.” EPA has also included debriefing questions in the survey instrument that are designed to identify individuals whose responses are based on incorrect interpretation of the environmental changes described in the survey, including the uncertainty of the expected changes. EPA points out that debriefing sessions during focus groups and cognitive interviews showed that respondents clearly understood that the ecological changes described in the survey were uncertain. Furthermore, when asked, focus group respondents indicated that they were comfortable making decisions in the presence of uncertainty.

Another commenter questioned various components of EPA proposed sampling methodology, experimental design, and methods for accounting for non-response bias. In response, EPA emphasizes that methods for WTP estimation from ecological choice experiment data—of exactly the type proposed by EPA—are very well established in the published literature. More broadly, when designing the proposed methods, EPA closely followed accepted contemporary methods in the published literature for the estimation of WTP distributions under statistical uncertainty. In the absence of concrete and established alternatives for the choice of sampling weights, EPA has proposed a more conservative approach of reliance on accepted and standard methods from the stated preference literature. EPA believes—following guidance in the literature and its own guidance documents (Arrow et al. 1993; US EPA 2000) for a weighting and extrapolation approach—that established stated preference methods are capable of estimating reliable and accurate welfare measures, if surveys and approaches are appropriately designed. Regarding the potential for non-response bias, EPA has proposed standard approaches for non-response assessments and calibrations in proposing tests and corrections for non-response based on a small number of attitudinal and behavioral questions, combined with demographic characteristics. These currently reflect standard practice within the literature.

Another commenter argued that although the Supreme Court held that Clean Water Act section 316(b) does not prohibit the consideration of costs in relation to benefits of proposed rule it did not find that cost benefit analysis is required (Entergy Corp. v. Riverkeeper, Inc.). EPA has the authority to decide whether to conduct cost benefit analysis of proposed rule options. The commenter, however, recognized that Executive Order 12866, “Regulatory Planning and Review,” requires EPA to estimate potential costs and benefits to society of proposed rule options. In response to the commenter’s claim about utility of cost-benefit analysis in environmental context, EPA notes that cost-benefit analysis is only one tool that can be used to inform policy decisions. EPA is conducting this survey because of Executive Order 12866, “Regulatory Planning and Review,” which requires Federal Agencies to conduct economic impact and cost-benefit analysis for all major rules. Furthermore, cost-benefit analysis requires a comprehensive, estimate of total social benefits, including non-use values. The current information collection would provide valuable information regarding total social benefits of the 316(b) regulation for existing facilities, thus enabling the Agency to perform cost-benefit analysis for the regulation, if it should choose to, without ignoring a potentially important category of benefits (non-use values), and to satisfy the requirements of Executive Order 12866.

For a more detailed discussion of the issues raised by commenters on this ICR, see EPA’s response to public comments on the Federal Register notices published on July 21, 2010 (74 FR 42438) and January 21, 2011 (76 FR 3883). For a discussion of the issues raised by commenters on the previous Phase III survey ICR, see EPA’s response to public comments on the Federal Register notice published on June 9, 2005 (70 FR 33746). For a discussion of issues raised by commenters on the previous Phase III focus group ICR, see EPA's response to public comments on the Federal Register notice published on November 23, 2004 (69 FR 68140).

3(c) Consultations

The Principal Investigator for the stated-preference portion of this effort is Dr. Robert Johnston. Dr. Johnston is assisted by Dr. Elena Besedin, a Senior Economist at Abt Associates Inc. Dr. Erik Helm at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency serves as the project manager and a contributor to this research.

Robert J. Johnston is Director of the George Perkins Marsh Institute and Professor of Economics at Clark University. He is President-elect of the Northeastern Agricultural and Resource Economics Association (NAREA), on the Program Committee for the Charles Darwin Foundation, the Science Advisory Board for the Communication Partnership for Science and the Sea (COMPASS), and is the Vice President of the Marine Resource Economics Foundation. Professor Johnston has published extensively on the valuation of non-market commodities (goods, services, and resources), benefit cost analysis, and resource management. His recent research emphasizes coordination of ecological and economic models to estimate ecosystem service values, with particular emphasis on the role of aquatic ecological indicators. He has also worked extensively in methodologies for benefit transfer, including the use of meta-analysis. Professor Johnston’s empirical work on non-market valuation and benefit transfer has contributed to numerous benefit cost analyses conducted by federal, state and local government agencies in the US, Canada and elsewhere.

Elena Y. Besedin, a senior economist at Abt Associates Inc., specializes in the economic analysis of environmental policy and regulatory programs. Her work to support EPA has concentrated on analyzing economic benefits from reducing risks to the environment and human health and assessing environmental impacts of regulatory programs for many EPA program offices. She has worked extensively on valuation of non-market benefits associated with environmental improvements of aquatic resources. Dr. Besedin’s empirical work on non-market valuation includes design and implementation of stated and revealed preference studies and benefit transfer methodologies. Her recent work has focused on developing integrated frameworks to value changes in ecosystem services stemming from environmental regulations.

EPA notes that the current survey instrument is built upon an earlier version that was peer reviewed in January 2006. It incorporates recommendations received from the first peer review panel. Because the final product of this study meets the major technical work criteria specified in the Peer Review Handbook (U.S. EPA 2006) the Agency also plans to convene a peer-review panel to review the entire survey process, including the survey instrument, study results, and EPA’s final estimated results for the 316(b) Existing Facilities rulemaking, after the survey is completed.

3(d) Effects of Less Frequent Collection

The survey is a one-time activity. Therefore, this section does not apply.

3(e) General Guidelines

The survey will not violate any of the general guidelines described in 5 CFR 1320.5 or in EPA’s ICR handbook.

3(f) Confidentiality

All responses to the survey will be kept confidential to the extent provided by law. To ensure that the final survey sample includes a representative and diverse population of individuals, the survey questionnaire will elicit basic demographic information, such as age, household size, employment status, and income. However, the detailed survey questionnaire will not ask respondents for personal identifying information, such as names or phone numbers. Prior to taking the survey, respondents will be informed that their responses will be kept confidential to the extent provided by law. The survey data will be made public only after it has been thoroughly vetted to ensure that all potentially identifying information has been removed.

3(g) Sensitive Questions

The survey questionnaire will not include any sensitive questions pertaining to private or personal information, such as sexual behavior or religious beliefs.

4. The Respondents and the Information Requested

4(a) Respondents

The target population for the Stated Preference Survey is all individuals from continental U.S. households who are 18 years of age or older. Survey participants are selected randomly from the U.S. Postal Service Delivery Sequence File (DSF), which covers over 97% of residences in the U.S. The survey households that will be sampled from the DSF include city‐style addresses and PO boxes, and covers single‐unit, multi‐unit, and other types of housing structures. EPA will send a copy of the mail survey to a random stratified sample of 7,628 households. Approximately 2,288 of the adults of the 7,628 adults sent a survey are expected to return a completed survey.

For the selection of households, the population of households in the 48 states and the District of Columbia will be stratified by four study regions. There are a total of seven study regions for purposes of evaluating the 316(b) existing facilities rule benefits. For the purposes of the stated preference survey implementation, EPA uses four geographic regions: Northeast, Southeast, Inland, and Pacific. The Northeast region includes the North Atlantic and Mid Atlantic regions, the Southeast region includes the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico regions, the Pacific region includes states on the Pacific coast, and the Inland region includes all non-coastal states.

A sample of 2,000 households would complete a version of the survey which specifically addresses policies within their region. The total sample completing regional survey versions is allocated to each region in proportion to the total number households in that region with the restriction that at least 288 persons respond in each region. This is the number required to estimate the main effects and interactions under an experimental design model. The total sample size for each region is much larger then the minimum sample size required for model estimation for all but one region (Pacific). An additional sample of 288 households will receive a national survey version which addresses policies at the national scale. This sample would be distributed among the study regions based on the percentage of regional survey sample (as shown in Table A1) to ensure that respondents to the national survey version are distributed throughout the continental U.S. Part B of this document provides detail on sampling methodology.

Table A1 shows the stratification design for the geographic regions covered by the sample for this survey. More detail on planned sampling methods and the statistical design of the survey can be found in Part B of this supporting statement.

Table A1: Geographic Stratification Design |

|||

Region |

States Included |

Sample Sizea |

Percentage of Sample |

Northeast |

CT, DC, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT |

417 |

21% |

Southeast |

AL, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC, TX, VA |

562 |

28% |

Inland |

AR, AZ, CO, ID, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, MI, MN, MO, MT, NM, OK, ND, NE, NV, OH,TN, SD, UT, WI, WV, WY |

732 |

37% |

Pacific |

CA, OR, WA |

289 |

14% |

Total for Regional Surveys Versions |

U.S. (excluding AK and HI) |

2,000 |

100% |

National Survey Version |

U.S. (excluding AK and HI) |

288 |

- |

a Sample sizes presented in this table include only the 2,288 individuals returning completed mail surveys. |

|||

4(b) Information Requested

(I) Data items, including recordkeeping requirements

Households randomly selected from the U.S. Postal Service DSF database will be mailed a copy of the survey. The full text of the regional version of the mail survey for the Northeast region is provided in Attachment 1 and the full text of the national version of the mail survey is provided in Attachment 2. EPA revised the survey based on the findings of a series of seven focus groups conducted as part of survey instrument development (OMB control # 2090-0028). Additional information regarding focus group implementation is provided in Section 5(b). EPA has determined that all questions in the survey are necessary to achieve the goal of this information collection, i.e., to collect data that can be used to support an analysis of the total benefits of the 316(b) regulation.

The following is an outline of the major sections of the survey.

Relative Importance of Issues Associated with Industrial Cooling Water. The first survey question asks respondents to rate the general importance of (a) preventing the loss of fish caught by humans, (b) preventing the loss of fish not caught by humans, (c) maintaining ecological health in rivers, lakes, and bays, (d) keeping the cost of goods and services low, (e) making sure there is enough government regulation on industry, and (f) making sure there is not too much government regulation on industry. This question is designed to elicit the respondent’s general preferences for regulation, reductions in fish losses, and ecological health. It also places respondents in the mindset where they are cognizant of the range of issues associated with the use of cooling water by industrial facilities.

Concern for Policy Issues. The second survey question asks respondents to rate the general importance of protecting aquatic ecosystems compared to other issues that the government might address. This question is designed to remind respondents that there are other issues (such as public safety, education, and health) to which the government could direct funds, rather than spending these funds to prevent fish losses. Such questions are commonly used in introductory sections of stated preference surveys (e.g., Mitchell and Carson 1984), in order to place respondents in a mindset in which they are cognizant that there are substitute goods and policy issues to which they might direct their scarce household budgets.

Relative Importance of Effects. Question 3 asks the respondent to rate the importance of each of the effects captured by the five scores: (a) commercial fish populations (b) fish populations (for all fish), (c) fish saved, (d) condition of aquatic ecosystems, and (e) cost to my household. This question is designed to promote understanding of the scores by placing respondents in a mindset where they consider the meaning of each score and consider their general preferences for effects prior to considering specific policy options. The question also promotes understanding by telling the respondent that they can return to previous pages for reminders of what the scores mean.

Voting for Regulations to Prevent Fish Losses in the Respondent’s Region. Questions 4, 5, and 6 are “choice experiment” or “choice modeling” questions (Adamowicz et al. 1998; Bennett and Blamey 2001), and ask respondents to choose how they would vote, if presented with two hypothetical regulatory options (and a third “status quo” choice to reject both options) for waters within the respondents’ region (e.g., Northeast waters). Each of the multi-attribute options is characterized by (a) commercial fish populations (in 3-5 years) (b) fish populations (all fish; in 3-5 years), (c) fish saved per year (out of [total] fish lost in water intakes), (d) condition of aquatic ecosystems (in 3-5 years), and (e) an unavoidable cost of living increase for the respondent’s household. Following standard choice experiment methods, respondents choose the regulatory options that they prefer, based on their preferences. Respondents always have the option to vote for neither option—providing the status quo option is necessary for appropriate welfare estimation (Adamowicz et al. 1998). Advantages of choice experiments, and the many examples of the use of such approaches in the literature, are discussed in later sections of this ICR. Following standard approaches (Opaluch et al. 1993, 1999; Johnston et al. 2002a; 2002b, 2003b), respondents are instructed to answer each of the three choice questions independently, and not to “add up or compare programs across different pages.” This is included to avoid biases associated with sequence aggregation effects (Mitchell and Carson 1989). EPA will also vary the order in which the policy option attributes are presented across respondents, such as presenting household cost first or presenting fish saved per year lower in the list of choice question attributes. While complete randomization is impractical for the mail survey, the change in order would allow for a potential test of ordering effects.

Reasons for Voting “No Policy”. Question 7 is a follow-up to the prior voting questions, and asks respondents to identify the primary reason for voting no, if they always voted for “no policy” in questions 4-6. It is designed to identify respondents whose “no policy” responses are based on their budget constraint, respondents who do not consider fish losses important enough to vote for a policy, or respondents who ignored information presented in the survey and answered questions based on their general convictions and principles. In an electronic survey format, respondents who voted for a policy would not see this question, potentially reducing burden.

Respondent Certainty and Reasons for Voting. Questions 8 and 9 are follow-up questions to the prior voting. Question 8 assesses the certainty that respondents feel in their choice experiment responses, following methods of Champ et al. (2004; 2009), Akter et al. (2009), Kobayashi et al. (2010), and others. It is designed to identify respondents whose responses are based on incorrect interpretation of the resource changes and the uncertainty of ecological outcomes from policy options. EPA will evaluate respondent understanding when completing stated preference surveys using methods and approaches discussed in Boyle (2003), Kaplowitz et al. (2004), Bateman et al. (2002), Powe (2007) and others. Question 9 asks respondents to rate the effect of factors on their choices, and why they voted for or against the regulatory programs. Responses to such questions have been used in the literature to successfully control for hypothetical bias.

Recreational Experience. Questions 10 asks respondents how often they participate in specific types of water-related recreational activities within the last year. This question can be used to identify non-users of the fishery resource—thereby allowing the estimation of non-user values for I&E mortality reductions.2 Examples of this approach to estimation of non-user values are provided by Johnston et al. (2005a), Whitehead et al. (1995), Croke et al. (1986), Olsen et al. (1991), Cronin (1982), Whitehead and Groothuis (1992), and Mitchell and Carson (1981).

Fish Consumption. Question 11 asks responds whether they consume commercially and recreationally caught seafood. This information will be used to identify respondents that are potentially affected by changes in the commercial and recreational fisheries.

Demographics. Questions 12-22 ask respondents to provide basic demographic information, including age, gender, highest level of education, household size, household composition, zip code, employment status, and household income. This information will be used in the analysis of survey results, as well as in the non-response analysis.

Comments. The survey offers respondents a chance to comment on the survey.

The Agency will modify the survey instrument for each region relative to the regional survey shown in Attachment 1 for the Northeast region as follows:

Cover – The text on the cover reads “A Survey of Northeast Residents (CT, DC, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT)”. “Northeast Residents” and the list of included states will be changed to match the respondent’s region.

Cover – The photo on the cover is of a forage species (silversides) in found in the Northeast region. If that species isn't found in other regions, EPA will replace the cover photo with a similar substitute photo for a forage species relevant to that region.

Page 1 – The survey states that it “asks for your opinions regarding policies that would affect fish and habitat in the Northeast U.S.” “Northeast U.S.” will be replaced with the respondent’s region or simply, “the U.S.” for the national version.

Page 1 – Includes the statement that “Northeast fresh and salt waters support billions of fish.” “Northeast” will be replaced with the respondent’s region or “the U.S.” for the national version and “salt water” will be removed for the Inland region.

Page 2 - The survey states that “Cooling water use affects fresh and salt waters throughout the Northeast US, but 93% of all fish losses are in coastal bays, estuaries, and tidal rivers.” For the Southeast and Pacific regions and the national version of the survey, which include both salt water and freshwater facilities, reference to the Northeast region would be replaced with the name of the respondent’s region or “the U.S.” for the national version of the survey. The percentage of fish losses occurring in coastal bays, estuaries, and tidal rivers will also be changed to reflect regional or national losses. For the Inland region which only includes freshwater facilities, reference to salt water will be removed.

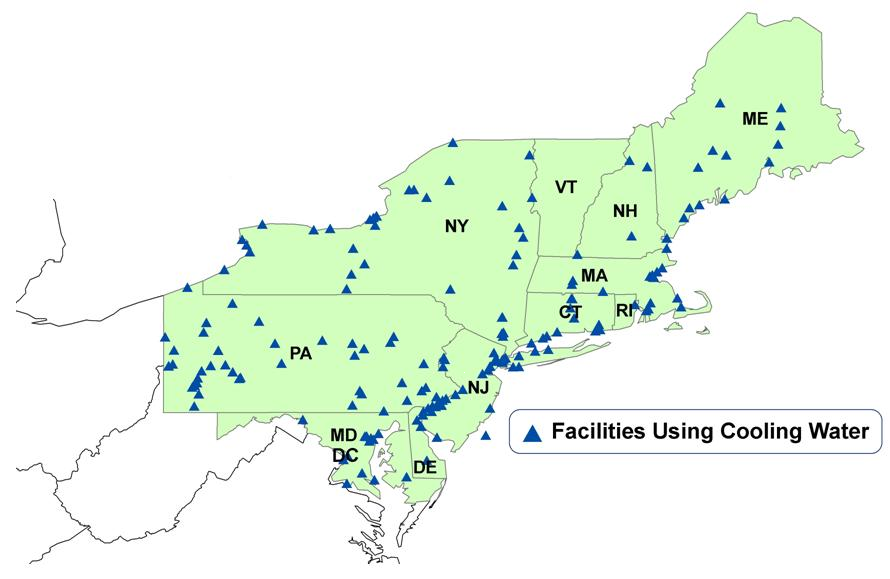

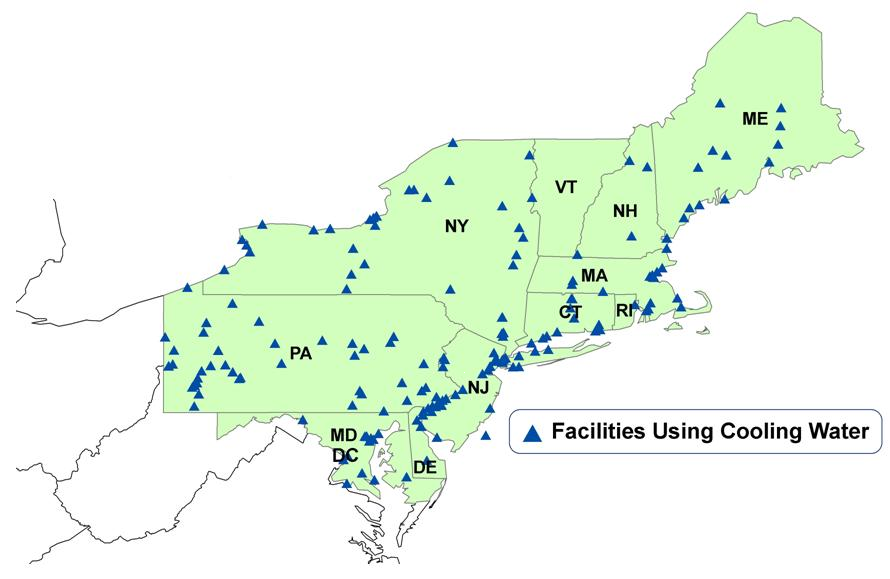

Page 2 – A map of the Northeast region and facility locations is presented. A comparable map will be produced for each region or the U.S., and map included in the survey will correspond to the respondent’s region or the U.S.

Page 4 - This page provides the range of fish saved under different policy options. This range will be updated to reflect totals for the respondent’s region or national totals.

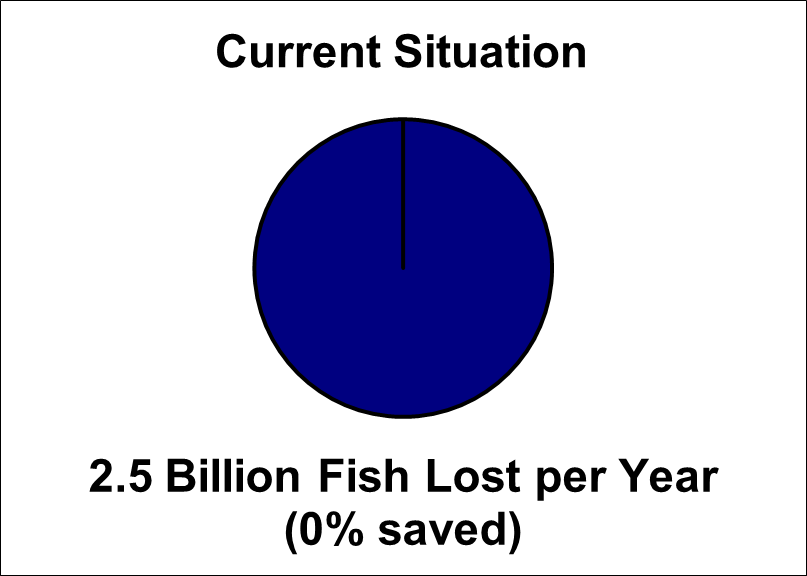

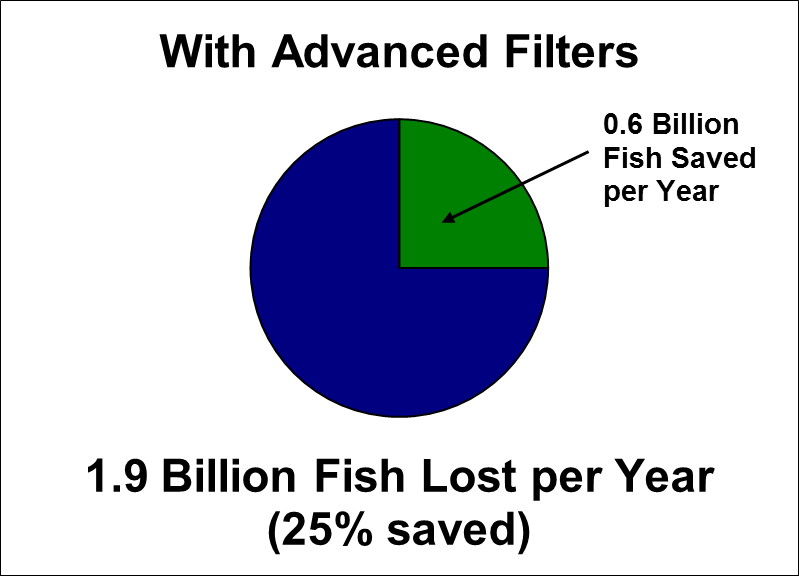

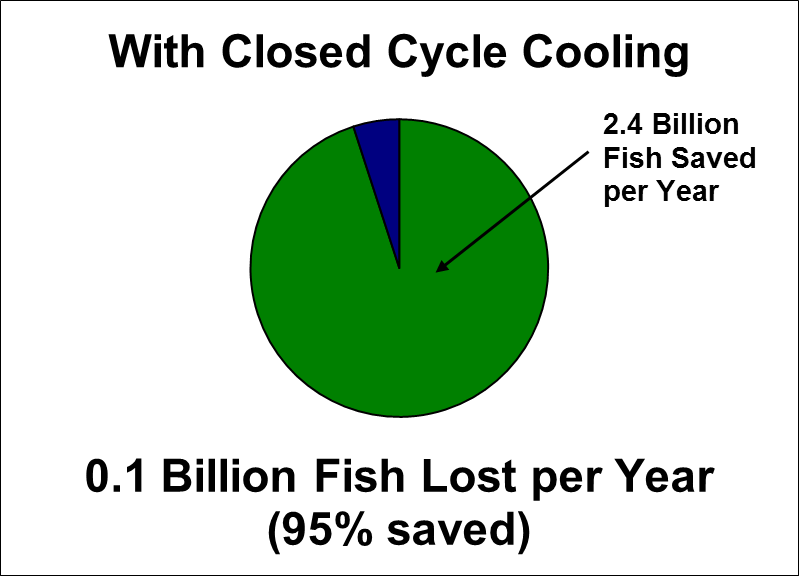

Page 5 - The total losses (1.1 billion) included within the survey correspond to losses from facilities in Northeast waters. This total would be replaced with the total losses for the respondent’s region or total losses for the U.S. for the national version. The pie charts will be updated based on the regional (national) total and percent regional improvements under policy options.

Page 7 - The table text describing each score will be changed to include the current scores for the respondent’s region.

Page 10 – The included figure illustrates the location of “Facilities Using Cooling Water Intake”. The figure will be replaced with a map showing facility locations within the respondent’s region or in the U.S. for the national version.

Pages 11-14 – Regional references within the table headings in Questions 4, 5, and 6 (e.g., “Policy Effect NE Waters””) will be modified to refer to the policy effects and options for the respondent’s region. The “Fish Saved per Year” score includes a note reminding the respondent of total fish lost within the region due to I&E (e.g., 1.1 billion); this number will be changed to reflect total losses within the respondent’s region or total national losses. The values describing the current situation and Options A and B within experiment questions 4, 5, and 6 will also vary across regions.

(II) Respondent activities

EPA expects individuals to engage in the following activities during their participation in the valuation survey:

Review the background information provided in the beginning of the survey document.

Complete the survey questionnaire and return it by mail.

A typical subject participating in the mail survey is expected to take 30 minutes to complete the survey. These estimates are derived from focus groups and cognitive interviews in which respondents were asked to complete a survey of similar length and detail to the current survey.

5. The Information Collected - Agency Activities, Collection Methodology, and Information Management

5(a) Agency Activities

The survey is being developed, conducted, and analyzed by Abt Associates Inc. and is funded by EPA contract No. EP-C-07-023 which provides funds for the purpose of analyzing the economic benefits of the proposed rule for existing facilities subject to the section 316(b) regulation. Agency activities associated with the survey consist of the following:

Developing the survey questionnaire and sampling design.

Randomly selecting survey participants from the U.S. Postal Service DSF database.

Printing of survey.

Mailing of preview letter to notify the household that it has been selected.

Mailing of surveys.

Mailing of postcard reminders.

Resending the survey to households not responding to the first survey mailing.

Mailing the follow-up letter reminding households to complete the second survey mailing.

Conducting a follow-up study of non-respondents to the mail survey using a combination of telephone and priority mailing to reach nonrespondents.

Data entry and cleaning.

Analyzing survey results.

Analyzing the non-response study results

If necessary, EPA will use results of the non-response study to adjust weights of respondents to account for non-response and minimize the bias.

Although not covered under this ICR, EPA will primarily use the survey results to estimate the social value of changes in I&E mortality losses of forage, recreational, and commercial species of fish, as part of the Agency’s analysis of the benefits of the 316(b) rule for existing facilities. If reliable environmental data were to be developed for population changes and other ecosystem impacts, social values for these benefit types may also be assessed for the rulemaking using survey results.

5(b) Collection Methodology and Information Management

To pretest the survey questionnaire, EPA conducted a series of seven focus groups, including one using cognitive interview methodologies under a different ICR (OMB control # 2090-0028). Focus groups provided valuable feedback which allowed EPA to iteratively edit and refine the questionnaire, and eliminate or improve imprecise, confusing, and redundant questions. Focus groups and cognitive interviews were conducted following standard approaches in the literature, as outlined by Desvousges et al. (1984), Desvousges and Smith (1988), Johnston et al. (1995), Schkade and Payne (1994), Kaplowicz et al. (2004), and Opaluch et al. (1993).

EPA plans to implement the proposed survey as a mail choice experiment questionnaire. First, EPA will use the U.S. Postal Service DSF database, to identify households which will receive the mail questionnaire. Prior to mailing the survey, EPA will send the selected households a preview letter notifying them that they have been selected to participate in the surveyand briefly describing the purpose of this study. The mail survey will be mailed one to two weeks after the preview letter accompanied by a cover letter explaining the purpose of the survey. The preview and cover letters are included as Attachments 6 and 7, respectively.

EPA will take multiple steps to promote response. All households will receive a reminder postcard approximately one week after the initial questionnaire mailing. The postcard reminder is included as Attachment 8. Approximately three weeks after the first round of survey mailing, all households that have not responded will receive a second copy of the questionnaire with a revised cover letter (see Attachment 9). A week after the second survey is mailed, a letter will be sent to remind households to complete the survey. The letter reminder is included as Attachment 10. Based on this approach to mail data collection, it is anticipated that approximately 30 percent of the selected households will return the completed mail survey. Since the desired number of completed surveys is 2,288, it will be necessary to mail surveys to 7,628 households (Dillman 2000).

Data quality will be monitored by checking submitted surveys for completeness and consistency, and by asking respondents to assess their own responses to the survey. Question 8 asks respondents to rate their understanding of the survey and their confidence in their responses. Questions 7 and 9 are designed to assess the presence or absence of potential response biases by asking respondents to indicate their reasoning and rate the influence of various factors on their responses to the choice experiment questions. Responses to the survey will be stored in an electronic database. This database will be used to generate a data set for a regression model of total values for reductions in fish I&E mortality by section 316(b) existing facilities.

To protect the confidentiality of survey respondents, the survey data will be released only after it has been thoroughly vetted to ensure that all potentially identifying information has been removed.

5(c) Small Entity Flexibility

This survey will be administered to individuals, not businesses. Thus, no small entities will be affected by this information collection.

5(d) Collection Schedule

The schedule for implementation of the survey will is shown in Table A2. The Northeast survey version will serve as a pilot study implemented ahead of other survey versions. Reponses and preliminary findings to the Northeast survey will be used to inform EPA regarding the response rates and the quality of survey data. EPA will evaluate Northeast responses and determine whether any changes to the survey instrument or implementation approach are needed.

Table A2: Schedule for Survey Implementation |

||

Activity |

Duration of Each Activity |

|

Northeast Version |

All Other Survey Versions |

|

Printing of questionnaires |

Weeks 1 to 2 |

Weeks 8 to 9 |

Mailing of Preview Letters |

Week 3 |

Week 10 |

Mailing of survey |

Week 4 |

Week 11 |

Postcard reminder (one week after initial survey mailing) |

Week 5 |

Week 12 |

Initial Data Entry and Pilot Tests |

Week 6 |

- |

Mailing of 2nd survey to non-respondents |

Week 8 |

Week 13 |

Letter reminder (one week after 2nd survey mailing) |

Week 9 |

Week 14 |

Telephone non-response interviews |

Weeks 11 to 13 |

Week 16 to 18 |

Ship priority mail non-response survey |

Week 11 |

Week 16 |

Data entry |

Weeks 4 to 14 |

Week 11 to 19 |

Cleaning of data file |

Week 15 |

Week 20 |

Delivery of data |

Week 16 |

Week 21 |

6. Estimating Respondent Burden and Cost of Collection

6(a) Estimating Respondent Burden

Subjects who participate in the survey and follow-up interviews will expend time on several activities. Based on the administration of the mail survey to 7,628 households, the national burden estimate for all respondents is 1,144 hours assuming that 2,288 respondents will complete and return the survey. Based on pretests conducted in focus groups, EPA estimates that on average each respondent mailed the survey will spend 30 minutes reviewing the introductory materials and completing the survey questionnaire. Thus, the average burden per respondent is 30 minutes (0.5 hours) for these 2,288 respondents to the mail survey.

EPA plans to conduct a non-response follow-up study that uses a short questionnaire and a combination of telephone and priority mailing. The short version of the questionnaire is included in Attachment 13. The short questionnaire will be administered by phone to 200 nonrespondents and by priority mail to 400 nonrespondents. EPA estimates that telephone non-response interviews will take 5 minutes (0.08 hours) per interview for each of the 200 households completing interviews. EPA estimates that each of the 400 households completing the mail version of the short questionnaire will take 5 minutes to do so (0.08 hours). Thus the average burden per respondent is 5 minutes (0.08 hours) for these 600 total participants in the non-response survey.

These burden estimates reflect a one-time expenditure in a single year.

6(b) Estimating Respondent Costs

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly wage for private sector workers in the United States is $20.42 (2009$) (U.S. Department of Labor 2009). Assuming an average per-respondent burden of 0.5 hours for individuals mailed the survey and an average hourly wage of $20.42, the average cost per respondent is $10.21. Of the 7,628 individuals receiving the mail survey, 2,288 are expected to return their completed survey. The total cost for all individuals that return surveys would be $23,360.

Assuming an average per-respondent burden of 0.5 hours for each of the 600 total participants in the non-response study and an average hourly wage of $20.42, the average cost per screening participant is $1.70. Therefore the total cost to participants in the non-response study phase would be $1,021.

EPA does not anticipate any capital or operation and maintenance costs for respondents.

6(c) Estimating Agency Burden and Costs

OMB approved implementation of the Northeast region of the stated preference survey as a pilot study conducted in advance of other survey versions. EPA has completed fielding both the Northeast mail survey and non-response follow-up study. A preliminary model has been estimated for the Northeast region and weighting adjustments are being assessed based on the results of the non-response study. The remaining survey versions (Inland, Southeast, Pacific, and National) are still being fielded. Agency and contractor burden has been updated within this ICR based on the response rates observed during the Northeast pilot.

For the main mail survey in the Northeast region, EPA received a total of 399 completed surveys for a 30% response rate equal to the rate assumed during development of the sampling frame. EPA administered the non-response survey via Priority Mail and telephone. The initial target sample sizes were 73 and 36 for the Priority Mail and telephone subsamples, respectively, for 109 total non-response contacts. For the Priority Mail subsample, EPA randomly selected 146 non-responding households based on an anticipated 50% response rate (73/0.5). The anticipated response rate was based on prior studies that administered surveys via Priority Mail. EPA actually received 48 completes from the Priority Mail sample giving a 33% response rate (48/146). Because the Priority Mail response was lower than expected, the target number of telephone completes was increased to obtain the desired number of responses. EPA randomly selected 331 households for the telephone survey from the subset of households with matched telephone numbers that did not complete the main mail survey or Priority Mail questionnaire. Fifty-one of the households had been previously sent, but did not return a completed Priority Mail questionnaire. The other 280 households (330-51) were sent a preview letter including a $2 incentive one week before the first telephone attempt. The telephone survey was divided into replicates to potentially cut down on cost if the required number of completes was achieved early. EPA made up to 12 attempts to achieve telephone contacts with the selected households. EPA stopped telephone calls after reaching the 63 completes within the 331 selected households, for a response rate of 19%. Revised estimates of agency and contractor burden for the non-response study were calculated by adjusting previous estimates upward based on the ratio of assumed response rates to response rates observed for the Northeast region (50%/33% for Priority Mail and 80%/19% for telephone). Respondent burden was unchanged because the target completes for the Priority Mail and telephone non-response samples were unchanged and estimated respondent burden is limited to time spent completing the survey.

This project will be undertaken by Abt Associates Inc. with funding of $355,969 from EPA contract EP-C-07-023, which provides funds for the purpose of analyzing the economic benefits of the proposed rule for existing facilities subject to the section 316(b) regulation. Abt Associates Inc. staff is expected to spend 5,952 hours pre-testing the survey questionnaire and sampling methodology, conducting the mail survey, conducting the non-response survey, and tabulating and analyzing the survey results. The cost of this contractor time is $$255,438. In addition to the effort expended by EPA’s contractors, EPA staff is expected to spend 320 hours managing and reviewing this project and contributing to the analysis at a cost of $31,000. Agency and contractor burden is 6,272 hours, with a total cost of $286,438 excluding the costs of survey printing and mailing. Mailing and printing of the survey is expected to take 133 hours and cost $100,531. Thus, the total Agency and contractor burden would be 6,404 hours and would cost $386,969.

6(d) Respondent Universe and Total Burden Costs

EPA expects the total cost for survey respondents to be $24,381 (2009$), based on a total burden estimate of 1,194 hours and an hourly wage of $20.42.

6(e) Bottom Line Burden Hours and Costs

The following table presents EPA’s estimate of the total burden and costs of this information collection:

Table A3: Total Estimated Bottom Line Burden and Cost Summary |

||||||

Affected Individuals |

Northeast Region |

Other Survey Regions |

Total – All Regions |

|||

Burden (hours) |

Cost (2009$) |

Burden (hours) |

Cost (2009$) |

Burden (hours) |

Cost (2009$) |

|

Mail Survey Respondents |

209 |

$4,257 |

936 |

$19,103 |

1,144 |

$23,360 |

Non-response Survey Participants |

9 |

$186 |

41 |

$835 |

50 |

$1,021 |

Total for Survey Respondents |

218 |

$4,444 |

976 |

$19,937 |

1,194 |

$24,381 |

EPA Staff |

58 |

$5,650 |

262 |

$25,350 |

320 |

$31,000 |

Survey Printing and Mailing |

24 |

$18,322 |

109 |

$82,209 |

133 |

$100,531 |

EPA's Contractors for the Mail Survey |

211 |

$14,034 |

944 |

$62,966 |

1,155 |

$77,000 |

Priority Mail Non-Response Subsample |

92 |

$9,512 |

410 |

$42,610 |

502 |

$52,122 |

Telephone Non-Response Subsample |

773 |

$22,737 |

3,522 |

$103,294 |

4,295 |

$126,316 |

Total Burden and Cost |

1,375 |

$74,983 |

6,223 |

$336,367 |

7,598 |

$411,350 |

6(f) Reasons for Change in Burden

The survey is a one-time data collection activity.

6(g) Burden Statement

EPA estimates that the public reporting and record keeping burden associated with the mail survey will average 0.5 hours per respondent (i.e., a total of 1,144 hours of burden divided among 2,288 survey respondents). Households included in the non-response study are expected to average 0.08 hours per screening interview participant (i.e., a total of 50 hours of burden divided among 600 non-response study participants). This results in a total burden estimate of 1,194 hours including both the mail survey and non-response study. Burden means the total time, effort, or financial resources expended by persons to generate, maintain, retain, or disclose or provide information to or for a Federal agency. This includes the time needed to review instructions; develop, acquire, install, and utilize technology and systems for the purposes of collecting, validating, and verifying information, processing and maintaining information, and disclosing and providing information; adjust the existing ways to comply with any previously applicable instructions and requirements; train personnel to be able to respond to a collection of information; search data sources; complete and review the collection of information; and transmit or otherwise disclose the information. An agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to, a collection of information unless it displays a currently valid OMB control number. The OMB control numbers for EPA's regulations are listed in 40 CFR part 9 and 48 CFR chapter 15.

To comment on the Agency's need for this information, the accuracy of the provided burden estimates, and any suggested methods for minimizing respondent burden, including the use of automated collection techniques, EPA has established a public docket for this ICR under Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2010-0595, which is available for online viewing at www.regulations.gov, or in person viewing at the Office of Water Docket in the EPA Docket Center (EPA/DC), EPA West, Room 3334, 1301 Constitution Ave., NW, Washington, DC. The EPA/DC Public Reading Room is open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday, excluding legal holidays. The telephone number for the Reading Room is 202-566-1744, and the telephone number for the Office of Water Docket is 202-566-1752.

Use www.regulations.gov to obtain a copy of the draft collection of information, submit or view public comments, access the index listing of the contents of the docket, and to access those documents in the public docket that are available electronically. Once in the system, select “search,” then key in the docket ID number, EPA-HQ-OW-2010-0595.

PART B OF THE SUPPORTING STATEMENT

1. Survey Objectives, Key Variables, and Other Preliminaries

1(a) Survey Objectives

The overall goal of this survey is to explore how public values (including non-use values) for fish and aquatic organisms are affected by I&E mortality at cooling water intake structures (CWIS) located at existing 316(b) facilities, as reflected in individuals’ willingness to pay for programs that would prevent such losses. EPA has designed the survey to provide data to support the following specific objectives:

To estimate the total values, including non-use values, that individuals place on preventing losses of fish and other aquatic organisms caused by CWIS at existing 316(b) facilities.

To understand how much individuals value preventing fish losses, increasing fish populations, improvements in aquatic ecosystems, and increasing commercial and recreational catch rates.

To understand how such values depend on the current baseline level of fish populations and fish losses, the scope of the change in those measures, and the certainty level of the predictions.

To understand how such values vary with respect to individuals’ economic and demographic characteristics.

Understanding total public values for fish resources lost to I&E mortality is necessary to determine the full range of benefits associated with reductions in impingement and entrainment losses at existing 316(b) facilities. Because non-use values may be substantial, failure to recognize such values may lead to improper inferences regarding policy benefits (Freeman 2003).

1(b) Key Variables

The key questions in the survey ask respondents whether or not they would vote for policies that would increase their cost of living, in exchange for specified changes in: (a) I&E mortality losses of fish, (b) commercial fish sustainability, (c) long-term fish populations, and (d) condition of aquatic ecosystems3. More specifically, the choice experiment framework allows respondents to view pairs of multi-attribute policies associated with the reduction of I&E mortality losses. Respondents are asked to choose the program that they would prefer, or to choose to reject both policies. This follows well-established choice experiment methodology and format (Adamowicz et al. 1998; Louviere et al. 2000; Bennett and Blamey 2001; Bateman et al. 2002). Important variables in the analysis of the choice questions are how the respondent votes, the amount of the cost of living increase, the number of fish losses that are prevented, the sustainability of commercial fishing, the change in fish populations, and the condition of aquatic ecosystems. Other important variables include whether or not the respondent is a user of the affected aquatic resources, household income, and other respondent demographics.

1(c) Statistical Approach

EPA believes that a statistical survey approach is appropriate. A census approach is impractical because contacting all households in the U.S. would require an enormous expense. On the other hand, an anecdotal approach is not sufficiently rigorous to provide a useful estimate of the total value of fish loss reductions for the 316(b) case. Thus, a statistical survey is the most reasonable approach to satisfy EPA’s analytic needs for the 316(b) regulation benefit analysis.

EPA has retained Abt Associates Inc. (55 Wheeler Street, Cambridge, MA 02138) as a contractor to assist in questionnaire design, sampling design, and analysis of the survey results.

1(d) Feasibility

The survey instrument was repeatedly pre-tested during a series of seven focus groups (conducted under a different ICR with OMB control # 2090-0028), in addition to the twelve focus groups conducted for the Phase III survey (EPA-HQ-OW-2004-0020), and it will be subject to peer review by reviewers in academia and government, so EPA does not anticipate that respondents will have difficulty interpreting or responding to any of the survey questions. Additionally, since the survey will be administered as a mail survey, it will be easily accessible to respondents. Thus, EPA believes that respondents will not face any obstacles in completing the survey, and that the survey will produce useful results. EPA has dedicated sufficient funding (under EPA contracts No. EP-C-07-23) to design and implement the survey. Given the timetable outlined in Section A.5(d) of this document, the survey results will be available for timely use in the final benefits analysis for the 316(b) existing facilities rule.

2. Survey Design

2(a) Target Population and Coverage

The target population for this survey includes individuals from continental U.S. households who are 18 years of age or older. The sample will be chosen to reflect the demographic characteristics of the general U.S. population.

2(b) Sampling Design

(I) Sampling Frames

The sampling frame for this survey is the panel of individuals selected from U.S. Postal Service Digital Sequence File (DSF) to receive a mail survey. The overall sampling frame from which these individuals would be selected is the set of all individuals in continental U.S. households who are 18 years of age or older and who have a listed address. The DSF includes city-style addresses and P.O. boxes, and covers single-unite, multi-unit, and other types of housing structures with known business excluded. In total the DSF covers 97% of residences in the U.S.

For discussion of techniques that EPA will use to minimize non-response and other non-sampling errors in the survey sample, refer to Section 2(b)(II), below.

(II) Sample Sizes