Evaluation Plan

Attachment 2_Evaluation Plan.doc

Drug Free Communities Support Program National Evaluation

Evaluation Plan

OMB: 3201-0012

Attachment 2:

Drug Free Communities Support Program National Evaluation Plan

Drug Free Communities Support Program

National Evaluation Plan

Final

December 27, 2010

R eport

prepared for the:

eport

prepared for the:

White House Office of National Drug Control Policy

Drug Free Communities Support Program

by:

ICF International

9300 Lee Highway

Fairfax, VA 22031

under contract number BPD-NDC-09-C1-0003

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to the Drug Free Communities (DFC) Program 2

DFC National Evaluation Logic Model 2

The SAMHSA Strategic Prevention Framework 2

Objective 1: Strengthen Measurement of Process Data 2

Objective 2: Refine Process Data with New Metrics on Coalition Operations 2

Objective 3: Report Outcomes and Strengthen Attribution between Processes and Outcomes 2

Objective 4: Deconstruct Strategies to Identify Best Practices 2

3. Data Collection and Management 2

Coalition Online Management and Evaluation Tool 2

Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) 2

Steps to Improve Data Quality 2

Facilitating Data Collection 2

Technical Assistance to Grantees 2

Analyzing Grantee Feedback from Technical Assistance Activities 2

Drug Free Communities Support Program

National Evaluation Plan

Final: December 27, 2010

The analysis plan outlined in this document is designed to provide ONDCP with strong evidence and useful results tailored to the needs of various stakeholder groups (i.e., SAMHSA, DFC grantees, community partners, etc.). Our approach will ensure that we not only continue to strengthen ONDCP’s Government Performance Results Act (GPRA) and Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART) reports, but also continue to provide results that can be used by coalitions to enhance their operations and capacity, and ultimately, improve their performance in reducing community-level youth substance use rates.

The scope of the evaluation described in this attachment is specific to Drug Free Communities (DFC). This analysis plan is not intended to be simply the product of our initial planning efforts; rather, it will become a “living, breathing document” which will be used as a point of reference throughout the five-year evaluation contract. The maintenance of this plan will ensure that all major decisions concerning the analysis are stored in a single location. It will also ensure that new staff on the contract will quickly overcome any learning curve and become fully engaged in this effort as soon as possible.

1. Introduction to the Drug Free Communities (DFC) Program

The Federal government launched a major effort to prevent youth drug use by appropriating funds in 1997 for the Drug-Free Communities Act. That financial commitment has continued for more than a decade, and in Fiscal Year 2009, nearly 726 community coalitions across 50 States, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Palau, and Puerto Rico received grants to improve their substance abuse prevention strategies. With bipartisan support from Congress, the DFC Support Program provides community coalitions with up to $125,000 annually, with a maximum of $625,000 over five years with a maximum of 10 years. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), in partnership with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), funded 161 new grants in August 2009, with a goal to extend these long-term coalition efforts. ONDCP funded 169 new grants in fiscal year 2010.

Through these grants, coalitions increase collaboration among 12 sectors in a community to target the needs of youth, their families, and the community as a whole.1 The goals of these community coalitions are to: (1) increase collaboration among community agencies; (2) reduce risk factors and increase protective factors for youth; and (3) reduce substance use among youth.

E

Determining

“What Works” In

this evaluation, we want to go beyond defining “success”

at the coalition level. Each of the more than 700 DFC coalitions

has unique strengths, and by understanding those strengths on a

more granular level, we can provide more prescriptive guidance to

coalitions on how to improve their operations and to ultimately

achieve their objectives. DFC

coalitions aim to reduce substance use in their communities, as

measured in this evaluation by past 30-day use. Although this is

the core outcome measure of the evaluation, there are other key

outcomes that logically precede – and follow –

reductions in substance use. For example, precedents to reducing

substance use include changes in attitudes (reflected in

perceptions of risk and parental disapproval), environmental

changes in the community (e.g., better lighting in areas where drug

dealing takes place), and information sharing/education, which are

all the products of complex processes where community partners come

together to solve problems. We also expect reductions in substance

use to have ancillary impacts, such as reductions in fatal crashes,

reductions in crime, and even better academic performance. Although

DFC coalitions have a clear goal to reduce substance use, our

inquiries into “what works” will focus on all aspects

of coalition functions and outcomes, including community

collaboration, environmental strategies, changes in attitudes,

reductions in substance use, and other resultant outcomes from

reductions in substance use.

Operationalizing

the concept of “success” in coalition activities will

involve a two-step process. First, we will identify coalitions that

had consistent, positive movements over time on outcomes of

interest. We will then explore in depth the processes that would

logically cause those movements to take place. By triangulating

quantitative data and qualitative data gathered from coalition

staff, we can have confidence in the attribution between process

and outcomes.

Evaluation Background

For two decades, communities have expanded efforts to address social problems through collective action. Based on the belief that new financial support enables a locality to assemble stakeholders; assess needs; enhance and strengthen the community’s prevention service infrastructure; improve immediate outcomes; and reduce levels of substance use, DFC-funded coalitions have been able to implement strategies that have been supported by prior research.2 Research also shows that effective coalitions are holistic and comprehensive; flexible and responsive; build a sense of community; and provide a vehicle for community empowerment.3 Yet, there remain many challenges to evaluating them. Specific interventions vary from coalition to coalition, and the context within which interventions are implemented is dynamic. As a result, conventional evaluation models involving comparison sites are difficult to implement.4

Three major features of our evaluation approach allow us to expand upon previous analysis to include a far greater range of hypotheses concerning the coalition characteristics that contribute to stronger outputs, stronger coalition outcomes, and ultimately stronger community outcomes.

First, our approach will systematically deconstruct more encompassing measures (e.g., maturation stages) into specific constructs that are more clearly related to strategies and functions that coalitions must perform, and that define their capacity. This will provide measures of multiple coalition characteristics that may differentiate real world coalitions, may be important to producing effective coalitions, and may operate differently across different settings and in different coalition systems.

Second, our approach uses the natural variation approach, in which we constantly look and test for differences in coalition organization, function, procedure, management strategy, and intent which may provide concrete lessons on how to construct effective coalitions in diverse settings.

Third, our design and analysis uses a multi-method approach in which different “sub-studies” within the large DFC National Evaluation project umbrella can provide unique opportunities to contribute to project lessons. For example, the case study component of our design and analysis through the use of site visits will provide strong opportunity to implement many of the analyses identified in the discussion of the logic model that follows in the next section of this paper. The rich data attained during site visits to coalitions, combined with our process and outcome data, will serve this purpose. Over time, as the site visit data set grows in size, these rich measures will produce a valuable analytic database.

By better understanding the DFC Program and its mechanisms for contributing to positive change, the National Evaluation can deliver an effective, efficient, and sensitive set of analyses that will meet the needs of the program at the highest level while also advancing prevention science.

DFC National Evaluation Logic Model

At its first meeting in April 2010, the DFC National Evaluation Technical Advisory Group (TAG) identified the need for revision of the “legacy” logic model prepared by the previous evaluator. A Logic Model Workgroup was established and charged with producing a revised model that provides a concise depiction of the coalition characteristics and outcomes that will be measured and tested in the national evaluation. The TAG directed the Workgroup to develop a model that communicates well with grantees, and provides a context for explicating evaluation procedures and purposes.

The Workgroup held its first meeting by telephone conference in July 2010. In the following two months, the committee (1) developed a draft model, (2) reviewed literature and other documents, (3) mapped model elements against proposed national evaluation data, (4) obtained feedback from grantees through focus groups at the CADCA Mid-year Training Institute in Phoenix, (5) developed and revised several iterations of the model, and (6) produced the recommended logic model shown in Exhibit 1. The National Evaluation logic model has six major features, described below, that define the broad coalition intent, capacity, and rationale that will be described and analyzed in the National Evaluation.

Theory of Change. The DFC National Evaluation Logic Model begins with a broad theory of change that focuses the evaluation on clarifying those capacities that define well functioning coalitions. This theory of change is intended to provide a shared vision of the overarching questions the National Evaluation will address, and the kinds of lessons it will produce.

Community Context & History. The ability to understand and build on particular community needs and capacities is fundamental to the effectiveness of community coalitions. The National Evaluation will assess the influence of context in identifying problems and objectives, building capacity, selecting and implementing interventions, and achieving success.

Coalition Structure & Processes. Existing research and practice highlights the importance of coalition structures and processes for building and maintaining organizational capacity. The National Evaluation will describe and test variation in DFC coalition structures and processes, and how these influence capacity to achieve outcomes. The logic model specifies three categories of structure and process for inclusion in evaluation description and analysis:

Member Capacity. Coalition members include both organizations and individuals. Selecting and supporting individual and organizational competencies are central issues in building capacity. The National Evaluation will identify how coalitions support and maintain specific competencies, and which competencies contribute most to capacity in the experience of DFC coalitions.

Coalition Structure. Coalitions differ in organizational structures such as degree of emphasis on sectoral agency or grassroots membership, leadership and committee structures, and formalization. The logic model guides identification of major structural differences or typologies in DFC coalitions, and assessment of their differential contributions to capacity and effectiveness.

Coalition Processes. Existing research and practice has placed significant attention on the importance of procedures for developing coalition capacity (e.g., implementation of SAMHSA’s Strategic Prevention Framework). Identifying how coalitions differ in these processes, and how that affects capacity, effectiveness, and sustainability is important to understanding how to strengthen coalition functioning.

Coalition Strategies & Activities. One of the strengths of coalitions is that they can focus on mobilizing multiple community sectors for comprehensive strategies aimed at community-wide change. The logic model identifies the role of the National Evaluation in describing and assessing different types and mixes of strategies and activities across coalitions. As depicted in the model, this evaluation task will include at least the following categories of strategies and activities.

Information & Support. Coalition efforts to educate the community, build awareness, and strengthen support are a foundation for action. Identifying how coalitions do this, and the degree to which different approaches are successful, is an important evaluation activity.

Enhancing Skills. This includes activities such as workshops and other programs (mentoring programs, conflict management training, programs to improve communication and decision making) designed to develop skills and competencies among youth, parents, teachers, and/or families to prevent substance use.

Policies / Environmental Change. Environmental change strategies include policies designed to reduce access; increase enforcement of laws; change physical design to reduce risk or enhance protection; mobilize neighborhoods and parents to change social norms and practices concerning substance use; and support policies that promote opportunities and access for positive youth activity and support. Understanding the different emphases coalitions adopt, and the ways in which they impact community conditions and outcomes, are important to understanding coalition success.

Programs & Services. Coalitions also may promote and support programs and services that help community members strengthen families through improved parenting; that provide increased opportunity and access to protective experiences for youth; and that strengthen community capacity to meet the needs of youth at high risk for substance use and related consequences.

Community & Population-Level Outcomes. The ultimate goals of DFC coalitions are to reduce population-level rates of substance use in the community, particularly among youth; to reduce related consequences; and to improve community health and well-being. The National Evaluation logic model represents the intended outcomes of coalitions in two major clusters: (1) core measures data, which are gathered by local coalitions, and (2) archival data (UCR, FARS), which will be synthesized by the National Evaluation team. These data will be utilized to assess the impact of DFC activities on the community environment and on substance use and related behaviors.

Community Environment. Coalition strategies often focus on changing local community conditions that needs assessment and community knowledge identify as root causes of community substance use and related consequences. These community conditions may include population awareness, norms and attitudes; system capacity and policies; or the presence of sustainable opportunities and accomplishments that protect against substance use and other negative behaviors.

Behavioral Consequences. Coalition strategies are also intended to change population-level indicators of behavior, and substance use prevalence in particular. Coalition strategies are also expected to produce improvements in educational involvement and attainment; improvements in health and well-being; improvements in social consequences related to substance use; and reductions in criminal activity associated with substance use.

Line Logic. The National Evaluation Logic Model includes arrows representing the anticipated sequence of influence in the model. If changes occur in an indicator before the arrow, the model represents that this will influence change in the model component after the arrow. For the National Evaluation Logic Model, the arrows represent expected relations to be tested and understood: How strong is the influence? Under what conditions does it occur?

In summary, the National Evaluation Logic Model is intended to summarize the coalition characteristics that will be measured and assessed by the National Evaluation team. The model depicts characteristics of coalitions that will be described as they present themselves, not prescriptive recommendations for assessing coalition performance. This model is intended to guide an evaluation process through which we can learn from the grounded experience of the DFC coalitions who know their communities best. The model uses past research and coalition experience to provide focus on those coalition characteristics that we believe are important to well functioning and successful coalitions. The data we gather will tell us how community coalitions implement these characteristics, what works for them, and under what conditions. In this sense the model is an evolving tool -- building on the past to improve learning from the present and to create evidence-based lessons for coalitions in the future.

Exhibit 1. DFC National Evaluation Logic Model

Theory of Change: Well functioning community coalitions can stage and sustain a comprehensive set of interventions that mitigate the local conditions that make substance use more likely.

The SAMHSA Strategic Prevention Framework

The SAMHSA Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) is an integral component of the logic, data collection, and analysis proposed here. There are several reasons for this:

Continuity. The SPF guidance for assessing and implementing coalition planning, decision making, and performance improvement has been a part of the DFC initiative since its inception. The SPF is part of the training and guidance that grantees receive through participating in the initiative; it is incorporated into the data collection system and current tools used by the DFC Program; and is fundamental to the analysis and reporting on the DFC Program that has been completed to date (e.g., the maturation typology is based upon data that has the SPF stages incorporated into it). Given its central role in the development of the DFC initiative and evaluation efforts to date, maintaining the SPF as a key organizing concept for the evaluation is a high priority.

Important Step in Prevention Progress. SAMHSA’s introduction of the SPF was an important advancement for the prevention field. For more than two decades, the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) and other public, non-profit, and private organizations had sponsored research and evaluation concerning the causes and consequences of substance use and how to prevent it. This research has developed important knowledge concerning the epidemiology of initiation of substance use (e.g., risk and protective factors); important information concerning the social and individual consequences of use, including recent advances in understanding the biological impacts that contribute (e.g., recent research on the adolescent brain); and a growing body of knowledge on the effectiveness of specific policies, programs, and practices that have made the promotion of evidence-based practices possible. Research has also highlighted the importance of planning, implementation, and the use of data in promoting effective prevention initiatives, and has included important work on the role of community-based coalitions in promoting and sustaining community improvements. Notably, in the early 1990’s, SAMHSA launched the ambitious Community Partnerships Program through which hundreds of coalitions were funded and evaluated across the country. This initiative demonstrated the potential of community coalitions. It also demonstrated some of the most important challenges they faced. The Community Partnerships Program emphasized empowering local community members to identify and develop solutions to their community’s problems. Many partnerships faced challenges in effectively organizing and planning, and often struggled to identify strategies and actions that would help them achieve their goals. While the Community Partnerships Program produced notable successes that have had sustained impacts in the communities, it also produced important lessons on the tools and assistance that communities often need to plan and implement strategies using the growing knowledge about how to successfully meet real needs in their communities.5 Importantly, SAMHSA’s SPF incorporates many of the lessons learned from earlier research on community coalitions, and integrates them with the growing knowledge and capacity in prevention. It focuses attention on a planning, implementation, and evaluation process that addresses many of the needs that challenged coalitions.

SPF Contributions to Coalition Functions. Importantly, we will maintain and enhance our use of the SPF in organizing data collection and analysis to more thoroughly test its contributions to address community coalition needs. By addressing the lessons learned from studying coalitions, the SPF framework makes the following important contributions:

Process Components. The SPF identifies seven contributing factors for planning and managing effective prevention strategies: assessment, capacity, planning, implementation, evaluation, cultural competence, and sustainability. Each of these components requires an identifiable set of competencies and skills, and each makes an important, identifiable contribution to effective planning and management. While these components are not new in the discussion of prevention, they have often been treated in a fragmented manner with insufficient attention to their complementary roles. They provide a comprehensive reference for coalition practitioners and researchers. In addition, they provide a common language to the substance abuse prevention field for the purposes of community mobilization and planning.

Inter-relationship of Components. These seven components are often presented as five steps with cultural competence and sustainability as overarching considerations that pervade all five. We will refer to the first five components as steps at times in this plan because there is an approximate chronological logic to them. For example, assessment of need and capacity logically informs capacity building and strategic planning; evaluation information is logically produced and used after plans have been implemented and results observed. However, the SPF framework makes it clear that the five steps should be conceptualized as a continuous cycle. Indeed, specific coalitions may be strong in some steps when they enter the National Evaluation, and activities relative to the five steps occur simultaneously. Furthermore, cultural competence and sustainability are criteria for consideration in each of these steps, and cannot be attained fully if they are not incorporated into each step. For example, one foundation for cultural competence must be information on the differential needs of diverse community populations. This must be a consideration in assessment of needs and existing capacity. As another example, research on sustainability has shown that developing workgroups involved in service delivery (not only planning) across agencies and organizations is crucial to sustaining (e.g., institutionalizing) innovations in activities and services. This requires consideration at planning and implementation stages, and cannot be handled as a separate process, or simply as a resource issue.

Systems Perspective. In addition, the SPF includes a systems perspective, emphasizing that these components produce results only when they work together in a single system. While coalitions will have different emphases and skill levels across the five SPF steps, and may accomplish them differently, it is critical that they all be addressed with reasonable effectiveness and balance. One of the issues confronting Community Partnership coalitions was an overemphasis on the planning function, with little clear connection to the activities that were eventually implemented. Similarly, a coalition cannot stay focused on real problems and progress without addressing the assessment and evaluation components of the SPF process. As noted above, sustainability and cultural competence will not be effectively achieved unless they are considered as characteristics of the entire system with implications for each component, and for system processes.

Evidence-Based Practice. The SPF creates a place and process for evidence-based practice to be incorporated into coalition planning. One of the persistent challenges to prevention practitioners in selecting and implementing evidence-based practices has been matching and adapting them to meet identified needs, environmental characteristics, population characteristics, and implementation capacity. Cultural competence is a particularly important consideration in SPF’s emphasis on linking these decisions to assessment, capacity building, planning, and evaluation. The adoption and maintenance of evidence-based practices and continuous quality improvement will contribute to longevity of positive outcomes, and institutionalization of effective policies, programs, and practices. SAMHSA has facilitated the adoption and adaptation of evidence-based practices by coalitions, which often must adapt to resource constraints and conditions in the community context, by providing more flexible guidelines that coalitions can use to make decisions about identifying policies, programs, or practices as evidence-based, identifying core components, and making appropriate adaptations. A final implication of SPF’s focus on systems is that evidence-based practice applies to organizational processes and capacity as well as to strategies and practices for interventions. For example, evidence on sustainability demonstrates that it requires resolving multiple concrete challenges, such as recruiting and maintaining participation, integrating and institutionalizing specific work relationships in the coalition system, maintaining long-term outcomes, and the acquisition of resources.

Importance of Context. The SPF framework and its focus on continuous, data-sensitive decision making places an emphasis on the importance of context, and the importance of continuous monitoring and consideration of local conditions. These community contexts are diverse, taking on distinct configurations across communities. For example, cultural competence may focus on racial/ethnic populations in one community, but focus on religious, socio-economic, or regional cultural values, beliefs and behaviors in others. The systems concept, and the focus on communities, makes context an important factor in prevention planning, decisions, and activities, as well as the measures and analyses used in the National Evaluation.

Data-Based Decision Making. Data-based decision making reflects the same orientation to empirically and scientifically-based policy and practice as the promotion of evidence-based practices, but with an important difference. While evidence-based practices use the accumulated, science-based knowledge produced through research and evaluation, the challenge is to apply this knowledge to a specific, current circumstance. Data-based decision making strives for real-time (or close to real-time) production of data that monitors needs, management of inputs and outputs, and attainment of outcome objectives to inform policy and management decisions by a coalition. The challenge is to produce accurate and reliable information that is relevant and can be used by decision makers. This means creating decision systems (processes) that make information available and set expectations for its use. Thus, the SPF process sensitizes practitioners to the importance of both the availability and the use of quality information. Consistent with the systemic perspective of the SPF, the capacity for both producing and using data must be developed. Evaluation within the SPF is an essential component of process and performance monitoring and feedback to inform decisions about improvement of coalition strategy.

SPF Challenges and Knowledge Development Opportunities. In addition to providing a framework for applying the research, evaluation, and experiential lessons generated in past studies and applications of prevention, the SPF provides an important guide for improving knowledge and practice. It also provides a guide for identifying the challenges that need resolution to achieve further improvement in research-based knowledge and its application in prevention. Accordingly, our research design, data collection, and analysis plan will provide tests of current hypotheses about how implementation of SPF constructs will improve coalition functioning and community outcomes. We will do this by (a) developing improved, practical measures of the manner and strength of coalition implementation of each step, and the way in which the outputs of each stage contributed to other components of the process (e.g., to other steps, to sustainability, to cultural competence); (b) articulate specific hypotheses implicit in guidance about how to implement SPF steps, and expectations about their benefits on capacity and outcomes; (c) test these hypotheses using our process and outcome measures and the mixed-method analysis plan defined in Section 4 of this plan; (d) refine and strengthen theory about SPF application and impacts; and (e) test revised hypotheses concerning application of the SPF to improve each of the five component areas, and ultimately strengthen attainment of community outcomes. Examples of areas of opportunity for knowledge expansion include:

Are Expectations about SPF Best Practices Empirically Confirmed? As elaborated later in this plan, the current measures of SPF accomplishments are based on expectations about what constitutes strength in each area. The empirical evidence about how specific structural and procedural characteristics contribute to each component is limited, and these specifics are critical to providing relevant guidance to practitioners. Our analysis is designed to deconstruct the current conceptualization of each SPF step and assess more precisely and concretely how coalitions organize and act to successfully fulfill the necessary functions of each SPF step.

How Can SPF Practices Be More Objectively Measured? Currently, measures of progress in core components are largely based on the perceptions of an informed observer in each local coalition. This reliance on a single observer has potential for measurement error (random and non-random) that may compromise the sensitivity and value of the SPF construct in our analyses. We will assess this potential with analyses of consistency, discrimination, and correlation, and recommend feasible improvements to establish more objective behavioral and event indicators.

Do SPF Best Practices Differ by Setting? Current knowledge concerning the SPF assumes significant homogeneity in the markers of accomplishment in each of the components. The diversity of coalitions and their settings is emphasized in past DFC reports, but it is not empirically specified, nor are the implications for approaches to successfully meet SPF functions. Our design and analysis provides tests of these conditions.

How Do SPF Best Practices Contribute to Maturation? Research on coalition functioning generally, and on DFC coalitions specifically, has identified coalition maturation – the systematic building of capacity that will improve effectiveness in attaining outcomes – as a central concept in developing knowledge and best practices with respect to community coalitions. While the maturation concept is widely used, there is little consensus on exactly what coalition structures, procedures, or activities are most important to defining it, or exactly how it contributes to effectiveness in achieving outcomes. The evaluation of earlier cohorts of DFC coalitions developed a measure of coalition maturation called the Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) that provided criteria for assigning coalitions to levels of maturation. The SPF components are central to this measure, which assesses maturity in part by how well respondents report capacity in the SPF components. However, analysis demonstrated that these classifications could not be empirically validated with the statistical models that were used. Furthermore, there is no specific, deconstructed analysis of how these components contribute to maturation in different areas. Our design and analysis addresses this important specification of empirical knowledge by (a) developing better measures of the empirical manifestations of capacity in each step, and (b) testing their relationship to capacity and community outcomes.

What Components/Dimensions Are Core? The SPF is a complex construct with multiple domains (components and crosscutting concepts) and dimensions within each domain. As with any strategy or program, the potential identification of core elements is of great value by specifying what functions and achievements are most important to output and outcome objectives. We will review existing work on these domains and dimensions (e.g., Renee Boothroyd’s literature review on core competencies [15] and essential processes [12] within the SPF) and use this input in the development of deconstructed measures that will help identify the relative contribution of SPF domains and dimensions to coalition capacity and outcome effectiveness.

How Do SPF Steps Work Together as a Cohesive System? As a final example, one of the important contributions of SPF noted above is that it provides a systems perspective. However, little of the evaluation or research on the SPF to date concerns the specification of how this system works. What makes an implementation of the SPF system coherent? What makes outputs (e.g., a needs assessment) from one SPF step useful for decisions that enhance output in another step, and ultimately in community outcomes?

In sum, we see the SPF as a central organizing feature of our evaluation. It has the great strength of being widely applied in current prevention research, evaluation, policy, and practice. This currency will strengthen the relevance of the DFC National Evaluation to practitioners in the field. It also provides a strong and organized guide for advancing knowledge concerning community-based prevention planning, policy, and practice. Subsequent sections of this analysis plan provide more detail concerning how our multi-method design and analysis will provide evidence concerning the evaluation issues and questions identified above.

2. Evaluation Framework

O

Deconstructing

Evidence Numerous

independent efforts have been undertaken to identify evidence-based

research on social programs, such as the U.S. Department of

Education’s What Works Clearinghouse, RAND’s Promising

Practices Network, and SAMHSA’s National Registry of

Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP). Typically, when

evidence of a program’s effectiveness is found, an

intervention/program will get a “seal of approval” from

these entities. In order for research to be truly useful to

practitioners, however, we must deconstruct the evidence and

identify core elements or practices that lead to better outcomes.

Put another way, communities

cannot pursue effective replication strategies by simply knowing

which coalitions are working; rather, they must know why they work,

how they work, and in what situations they work.

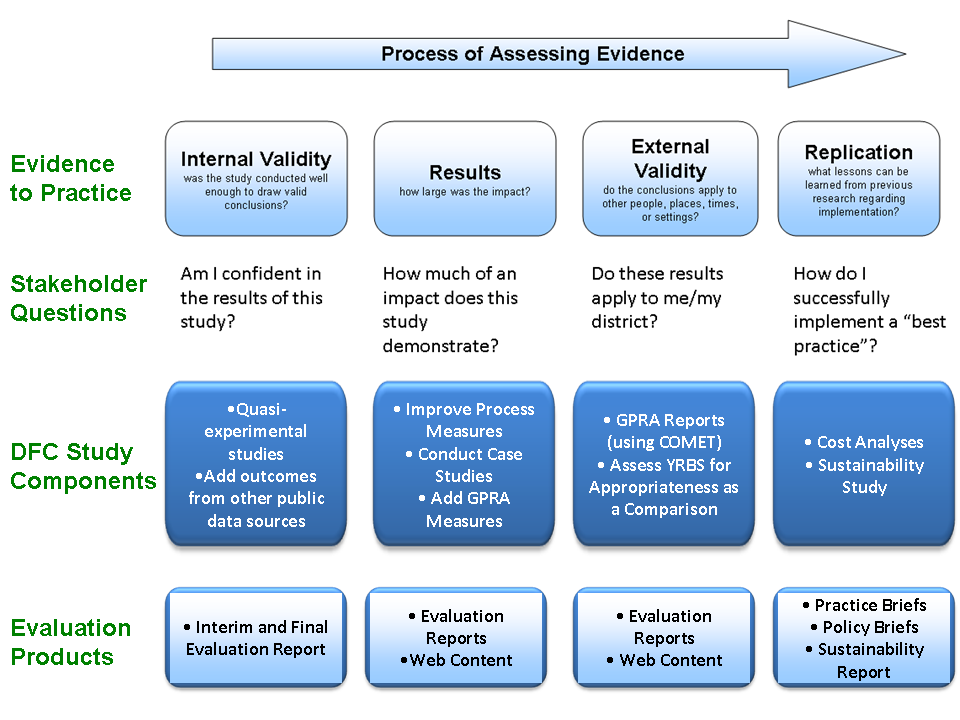

Exhibit 2 presents a top-line overview of our study design. This exhibit describes the (1) process of moving evidence to practice, (2) key stakeholder questions at each evaluation stage, (3) proposed study components that address each step in the process, and (4) proposed evaluation products that provide high-quality performance reporting, rigorous evaluation reports, and practical products that can aid in the replication of evidence-based practices.

Exhibit 2. Process of Assessing DFC Evidence

Moving Evidence to Practice

When a consumer of research–such as a legislator, school board member, or coalition member–reviews the effectiveness of various strategies, he or she is likely focused on a single question:

Will this strategy work in my community?

Many efforts currently underway do not go beyond assessing the quality of a study and its results, leaving the consumer to determine whether a strategy could be successfully replicated (and effective) in its community.6

While the assessment of whether a study’s results are generalizable is a qualitative judgment best left to staff on the “front lines,” there is still a great need to present information in a manner to help stakeholders make these types of judgments. In this evaluation, we will strive to provide a sufficient level of detail so every decision maker at the Federal, State, and local level can decide upon his or her best course of action to pursue in addressing prevention efforts.

The top of Exhibit 2 presents a simplified framework for assessing evidence from both a researcher’s and a consumer’s point of view. The first step in the process is to assess the research evidence on a particular intervention and determine whether the study used scientific methods that could generate valid conclusions. Researchers call this “internal validity” and from a consumer’s perspective, the implication of internal validity is to determine whether the results of the study are believable in the first place. Our evaluation design is intended to have sub-studies with strong internal validity; namely, the quasi-experimental comparison group studies. Other analyses that do not employ a comparison group design (e.g., GPRA reports) will have somewhat lower internal validity.

Next, both researchers and consumers have to determine whether the study produced effects that are meaningful. The degree to which results are meaningful can be determined in two major ways. The first focuses on the magnitude of the effect. Many researchers use the concept of statistical significance to determine whether a particular study had an effect; however, this is not necessarily a good idea since statistical significance is heavily dependent upon sample size, and because the most rigorous research (e.g., randomized studies) is often too costly to implement on a large scale. For example, with a study sample of 10,000 students, even small effects will be statistically significant while a sample of 50 students will rarely produce statistically significant results, even with relatively large effects. Ultimately, what matters most is not statistical significance alone, but rather, whether the size of an effect is meaningful in a practical sense. Researchers use the concept of effect size to determine this. In this evaluation, we will present evidence based on effect sizes, which tells us not only if results are meaningful, but also how results compare on different outcomes (e.g., we can put all results on a common scale so we can assess whether a given coalition had, for example, stronger results on perceptions of risk than they did on age of onset).7 The second way in which results can be determined to be meaningful is the established strength of the relationship on an observed outcome to associated, and often distal, outcomes. For example, the relationship of binge drinking to future consequences is much stronger than that of simple 30-day use. Any behavioral measure of use has a stronger relation to consequences than perceived health risk. We will incorporate the growing research evidence on the strength of outcome indicators as predictors of consequences, as well as the prevalence of the behaviors, into our measurement of results.

If studies are conducted well and if results are meaningful, the next step is to determine whether the results are generalizable. Researchers call this “external validity” and it is an important factor to consider in the adoption of any program. Consumers of research will likely want to know whether findings can be applied to their communities and it is important to present sufficient context for State and local decision-makers to make informed choices on which strategies to adopt.

Finally, once a piece of research is found to be believable, to provide meaningful effects, and to be applicable to populations or settings of interest, thought must be given to replicating (and potentially adapting) that program. Realistically speaking, localities adopt strategies/initiatives and then tailor those strategies to address their risk factors, youth, and budgets. This, oftentimes, renders research outcomes at a strategy level obsolete, since the specific parameters of the intervention have been changed. What matters more is knowing which elements of a particular strategy to keep and which ones can afford to be modified. That is the level of detail we will strive to provide through our analyses.

Evaluation Questions

Our ultimate goal in this next phase of the evaluation will be to implement a set of innovative, scientifically-based methods that will be both accepted by the research community and intuitive to non-researchers. Undoubtedly, this evaluation will need to address the concerns and needs of a number of stakeholders. Stakeholders in ONDCP, SAMHSA, and in the research and prevention communities will be focused on questions of internal validity and results of the DFC program, while stakeholders in the field will be focused on the identification of best practices and their replication. Our study design and analysis plan focuses on research questions that are relevant to key stakeholder groups, and, in collaboration with ONDCP, we will develop participative processes through which we can gather input from stakeholder groups concerning priority questions. One of our major emphases over the next five years will be to strengthen our design and analytic capability to answer relevant questions in ways that provide useful guidance based on the most rigorous and precise analysis possible within this initiative. Exhibit 3 provides a summary of select stakeholder groups (column 1), selected examples of research questions relevant to each stakeholder group (column 2), the products through which findings and lessons can be communicated to each group in a useful way (column 3), and a preliminary identification of analysis methods that our design will support, and that will provide answers to the questions (column 4).

Exhibit 3. Key Evaluation Questions, Products, and Analytic Methods Relevant for Each Stakeholder Group |

|||

Stakeholder |

Key Research Questions |

Products |

Methods |

ONDCP and SAMHSA |

|

|

|

Leaders of Coalitions |

|

|

|

Schools |

|

|

|

Local Governments |

|

|

|

Law Enforcement |

|

|

|

Social Service Agencies |

|

|

|

Judicial Agencies |

|

|

|

Exhibit 3 is a simple guide to the careful planning and implementation that will characterize our implementation of the evaluation design. A brief elaboration will demonstrate this point.

Relevance and Utility. A major part of making findings useful is ensuring that the intended stakeholders see the findings as “actionable” – that they provide implications and lessons that can be acted on and implemented in the real world context of a coalition. Second, it is important that intended audiences believe that the guidance will “work” – that it will have the intended effect. Involving key stakeholders in the identification of relevant questions is critical to meeting these criteria for utility. We will work with ONDCP to create multiple channels of participation for stakeholders, focusing on the issue of relevant and useful questions and information. Avenues may include sessions at appropriate conferences, webinars, web-based suggestion boxes, or Internet surveys.

Products. Research findings will not be used unless they are effectively disseminated and understandable. We will produce a variety of products designed to effectively convey information to the stakeholder groups, and will constantly monitor and improve the quality of these products through feedback from intended consumers.

Place in the Logic Model. Our comprehensive research and analysis design is necessary to gain the rich perspective that is important to understanding the many systemic and situational factors that must be understood to improve coalition effectiveness. Our experience has taught us that fragmentation of the design and in analysis (i.e., conducting specific analyses in relative isolation from findings and information throughout the study) works counter to the comprehensive and integrated intent of the overall design. Our implementation process will consistently ensure that we place each specific analysis in the larger study context and consider influences and implications in the full study context. Later sections of the analysis plan will make this integrated use of our multiple methods more specific.

Analysis Methods. The final column in Exhibit 3 identifies the sub-components of the analysis that will specifically address each question, and the components of the data set that will be used. This identification of method is preliminary and will be further specified as data sources are assessed and input on research questions is incorporated. The important point in early planning is to identify the need for specificity, and anticipate ways of developing necessary measures and analysis strategies.

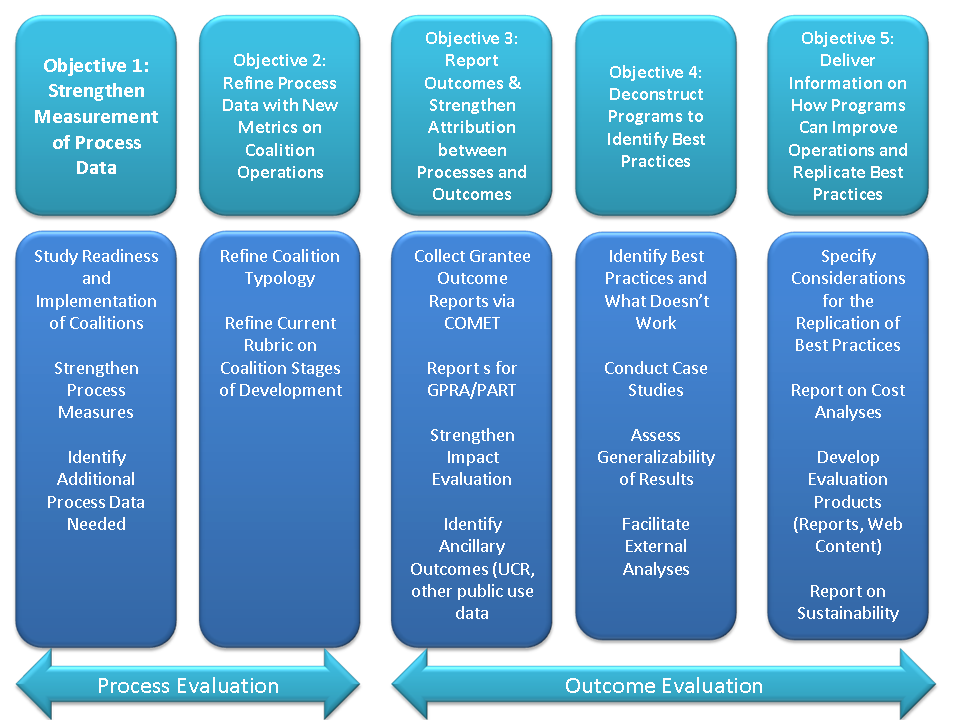

Exhibit 4 contains a simplified version of our evaluation plan. This exhibit demonstrates that there are five objectives (or stages) in the execution of this evaluation. They are:

Objective 1: Strengthen Process Measures. As stressed throughout this plan, our analyses will greatly increase the level of detail with which coalition strategies are described and differentiated. Thus, details will support analyses of the degree to which different coalition structures, procedures, strategies, and implementation characteristics contribute to the achievement of the grantee and community outcomes identified in our evaluation logic model (Exhibit 1). Strengthening process measures is simply the necessary foundation for answering many of the stakeholder research questions previewed in Exhibit 3.

Objective 2: New Metrics on Coalition Operations. The detailed measurement of process is necessary to accurately measure coalition structure, procedure, and activity. However, providing practical and generalizable guidance to coalition practitioners requires development of more encompassing metrics that characterize this detail in more general terms. These more general metrics “bundle” detailed measures into larger constructs that can guide planning, implementation, and capacity building across coalitions, and provide guidance to the settings, purposes, and populations to which they are most applicable. The Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) maturation categories are an example of such a multiple-item metric, and are the single major process measure in the previous evaluation. We believe that the CCT provides a single (yet important) dimension of coalition operations, and that other dimensions are needed (e.g., collaboration quality, types of coalition strategies, strength of implementation, capacity for SPF steps, cohesiveness, sustainability) to accurately encapsulate conceptually important process measures in analyses of outcomes. Our focus in this stage will be the development of new summary metrics – in addition to the maturation measure captured in the CCT – to further explain what is truly happening at the local level and how these other factors contribute to a coalition’s effectiveness.

Objective 3: Outcomes and Attribution. Simultaneous to the strengthening of process measures and coalition metrics, we will be strengthening community intermediate outcomes, substance use outcomes, and additional related outcomes (e.g., consequence data). Our design and analyses for demonstrating attribution of coalition effects on outcome measures has been strengthened through improved measurement and improved comparison design. The ability to explain the measurable coalition structures, strategies, and implementation characteristics that contribute to attaining outcomes has been provided by the strengthened process measures. These metrics can be entered into multivariate models, which can identify contributing factors and specify them across different community settings, organizational contexts, and populations.

Exhibit 4. Objectives and Evaluation Components

Objective 4: Identify Best Practices. Our focused analyses of contributions to effectiveness by different coalition strategies, our case study analyses, and our cross-site comparisons for site visit coalitions will contribute to a strong ability to identify best practices and test the degree to which they can be generalized.

Objective 5: Deliver Useful Best Practice Guidelines. The mixed-method richness of the analysis and interpretation provided by our evaluation design will support a variety of products, such as policy briefs and best practices briefs, to convey relevant, understandable, and useful lessons and best practices to policy makers, coalition practitioners, and other stakeholders and interested parties.

Objective 1: Strengthen Measurement of Process Data

As noted above, the strengthening of process data is fundamental to our approach to strengthening the attribution between process and outcome data (which can be extraordinarily difficult, especially at the community level). It also will provide tools to identify potential implementation challenges before they happen. The ICF team will conduct an in-depth study of core processes that are being implemented and cross-reference key developments in the literature, our Technical Advisory Group’s guidance, and our previous efforts working with coalitions to identify new process measures needed for collection. Our approach to strengthening process measurement involves the following steps.

Step 1. Literature Review. The development of stronger process measures will begin with a literature review. The team will develop parameters for the literature review, which will ensure that our efforts will stay focused on the core needs of the evaluation. In addition, the team will develop a structured abstract protocol that will ensure that the appropriate information is being collected. This literature review will be supplemented by past and current studies of coalition processes, many of which ICF team members have already conducted. For example, this will include:

Various surveys that focus on comprehensive community initiatives in the prevention arena.

State studies on SPF-SIG coalitions (e.g., Tennessee) have identified systemic features of coalition activity associated with stronger processes. For example, the presence of adult drug courts facilitates the use and effectiveness of environmental strategies related to DUI enforcement by providing systemic capacity to effectively address these cases and promote positive outcomes.

Studies of coalitions focusing on integrating services (e.g., SAMHSA’s Starting Early Starting Smart multi-site evaluation) have documented the importance of integrated line work groups for sustainability of innovation.

The substantial literature (both refereed and fugitive) produced concerning SAMHSA’s Community Partnerships Initiative. This is an important source because many of the focuses of the SPF and concepts of coalition functioning (e.g., various maturation or developmental models) were initially generated in the substantial research generated by this large and well-funded initiative. It will provide a strong basis for identifying both hypotheses concerning contributors to effectiveness and challenges commonly faced by coalitions.

Step 2. Review and Assessment of Current DFC National Evaluation Measures. Process measurement in the DFC National Evaluation to date has largely used data from two sources: (a) the Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) and (b) the Coalition Online Management and Evaluation Tool (COMET), a web-based performance monitoring system. Simultaneously with the literature review, we will conduct a thorough review and assessment of the current measures, their strengths and limitations, and make recommendations for their use, revision, or augmentation in the evaluation. Briefly, some of the relevant issues will include the following.

The Coalition Classification Tool. The CCT is a tool that asks an informed coalition member to provide judgments about the coalition’s performance or characteristics with regard to four functional areas: (1) Coalition development and management, (2) Coordination of prevention programs/services, (3) Environmental strategies, and (4) Intermediary of community support organization. Very little analysis of the data gathered through the CCT has been reported in published evaluation reports to date. Analyses of the association of maturation stages defined by the CCT to other judgments of coalition function, and, more importantly, analyses showing moderate association of coalition type to outcome effectiveness are the focus of what has been reported. This relative paucity of analysis reporting concerning this core source of process data raises several points.

The actual CCT maturation classifications are based on only a portion of the data gathered through the instrument. It uses six general rating items for each of the four functional areas identified above. The total measure includes 24 items. As noted, the CCT items are “global” which exacerbates several common problems with closed-ended key informant reports on organizational processes and status. First, the respondent is being asked to report on complex organizational processes from her individual perspective. Second, the item statements on which the respondent is to rate the organization’s performance from novice to mastery are often very complex, including multiple items that appear to be duplicative of one another (or so closely related, they are duplicative for all intents and purposes). It is difficult to know the precise empirical reference upon which the response is based. In short, these items do not provide clear empirical referents, and thereby need to be augmented with additional analyses if they are to provide clear “actionable” lessons learned.

There are many additional items in the CCT (in fact, more than 100), and many provide a more concrete empirical referent than the “general ratings” used in the CCT. For example, questions 3 and 4 in the CCT ask about characterizations of the organizational structure and status of the coalition. This is potentially important information concerning the diversity of coalition organization, and the need for assessing the homogeneity of best practice across different types. However, this information (and many other potentially useful items) has not been profiled or associated with CCT items, types, or the full range of items in the tool.

Accordingly, exploratory analyses of the CCT, including correlations and dimensional and clustering analyses will be a primary analytic product in our evaluation plan.9 This analysis will include the entire instrument, and not just the small number of items that are included in the maturation typology. The objectives will be (a) to better understand the profiling [e.g., similarities and differences, both univariate and multivariate] of coalitions that is important to understanding whether analyses can be meaningfully aggregated or must be disaggregated; (b) to assess the measurement quality of CCT items; and (c) to assess the degree to which CCT items, scale scores, or sub-scale scores correlate.

These analyses will provide substantial information on the degree to which CCT items form dimensions or clusters, the quality of items in terms of variation and contributing to these measurement dimensions, and the degree to which groups of items may form meaningful measures of strategies or capacities that vary across coalitions.

Coalition Online Management and Evaluation Tool Items. COMET process data has received even less analytic attention than CCT in DFC National Evaluation analyses to date. The National Evaluation team has begun a process of sorting, organizing, and analyzing COMET data that is similar to that described above for the CCT items. The COMET data provides opportunity for several important types of exploration.

We will identify variables that can help profile the amount and nature of diversity in coalition characteristics, and the degree to which they may form distinct types of strategy, structure, or some other set of coalition structures, procedures, or implementation characteristics. For example, the reporting of strategies will support analysis of the frequency and distribution of strategies, whether strategies tend to co-occur to form distinct types, and what proportion of coalitions fall into distinct types.

We will organize reporting into longitudinal repetitions suitable for assessing change and development relevant to the grantee outputs and outcomes in the logic model. This may allow more precise tests of maturation based on strategies rather than perception, or tests of the sequencing of events (e.g., increases in quality of implementation following TA and training events).

We will match select data from COMET with CCT data and assess consistency (correlations) of items/measures hypothesized to change together. These may be alternate measures of the same construct, or measures that would be hypothesized to vary together or sequentially based upon the logic model and theories of coalition development or intervention effect. In this manner, analyses could be used to cross-check and validate findings or indicate areas for further exploration.

These analyses will greatly increase our ability to assess the measurement quality of existing measures, to identify those that may be replaced,10 and to better understand the characteristics and diversity of coalitions.

Map Measures Against Elaborated (Internal) Logic Model. Based on the literature review and enhanced understanding of the profile and diversity of DFC coalitions, we will revise and elaborate the logic model identifying conceptually important constructs that should be measured at each stage of the model. This task was recently completed by the Logic Model Workgroup and details of the internal logic model are presented in Exhibit 5. We will then map the potential measures from existing data onto these constructs, and identify needs for revision or addition of measures.

Recommend Revisions in Measures. Following this cross-reference of the key processes and constructs identified in the literature with specific survey items from well-known prevention surveys (including our own and existing COMET data collection), the team will recommend the measures for future data collection. We will then present these findings to our COTR for review and comment, and where possible, we will propose that new measures be implemented in a checklist or matrix format (i.e., instead of moving to a new screen for each activity, checklists or matrices will be developed to capture all data on activities on a single screen).

Before any new measures are approved, the ICF team will assess response burden for these additional questions, as well as expected response burden for the entire data collection effort. Specifically, we will assess not only the time it takes to complete all data collection requirements for DFC, but also the time it takes to transfer data from one source to another. Many coalitions have multiple data collection requirements from multiple funders, and our burden-reduction efforts must take these other requirements into consideration. By identifying strategies to streamline data collection and reporting efforts all funders (either through minimum data set or data export strategies), we will ensure that the totality of response burden is considered.

For DFC requirements specifically, we will aim to make any changes time-neutral in terms of response burden, as we want to ensure that prevention practitioners stay focused on their jobs and not on data collection requirements. We expect that making a good-faith effort to keep response burden down will also result in stronger buy-in for evaluation activities from practitioners.

Exhibit 5. Internal DFC National Evaluation Logic Model

CONTEXT |

Coalition Structure and Processes |

Strategies and Activities |

COALITION CAPACITY |

COALITION EFFECTIVENESS |

Community

Coalition

|

Member Competency

Structure

Processes

|

Coalition Role

Programmatic Capacity

Strategy / Activity Mix

Coalition & Community Outputs

|

Coherence

Coalition Climate

Positive External Relations

Capacity Building Effort

|

Community/ System Outcomes |

Norms & Awareness

Systems & Policy Change

Sustainable Accomplishments

|

||||

Community Behavioral Outcomes |

||||

Substance Use Prevalence

Contributors & Consequences

|

Discussion: Examples of Potential Additional Process Variables

From our review of existing data collection protocols, we can predict that the likely outcome of this effort will be a focus on measures of implementation quality. While the current evaluation has focused process measures on a coalition’s stage of development, this only tells part of the story. Even more important (and more difficult to measure) is the quality of the coalition’s collaboration and outreach efforts. We expect that adding dimensions to our understanding of coalition processes will put us in a more favorable position to present useful outcomes to ONDCP, its Federal partners, prevention practitioners, and other stakeholders in this evaluation. By defining quality processes, we will also be in a better position to help ONDCP and other stakeholders provide guidance and assistance to DFC grantees, as well as recommend new criteria for the grants award process.

Collaboration Quality

While the evaluation field has not fully investigated how certain collaborative variables and dynamics lead to successful coalitions, it is not due to a lack of measures. In 2004, Granner and Sharpe identified more than 140 different measures of scales of collaborative variables through a literature and web-based search. We can identify adequate measures from Granner and Sharpe’s (2004) review, but ICF also has established measures and has been very successful at tailoring them to specific community change initiatives in the past. In determining the addition of a new measure, the first and most important issue is relevance: is the variable truly meaningful to the majority of DFC communities and is it relevant or integral for evaluation purposes? In terms of psychometrics, a major issue is reliability (the consistency of a measure), and a common rule of thumb is that measures should have a reliability of .70 or higher (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). On the other hand, another aspect that drives reliability is the number of items –more items results in higher reliability, but also increased burden on respondents. To provide some context as to what new process measures may strengthen the evaluation, below we briefly summarize some initial or preliminary thoughts that could be the starting point of our collaborative discussion about what process measures can add value to the evaluation and inform practice.11 The National Evaluation team will follow up the submission of this evaluation plan with appendices that document, at the variable/item level, recommendations as to whether items should be retained, augmented, or replaced in order to improve upon process measurement and provide the team with the ability to link quality process measures to quality outcome measures.

Grantee Readiness for DFC

The field of community change and comprehensive community initiatives has long stressed the importance of “readiness for change” as a major variable distinguishing successful from unsuccessful coalition efforts (Donnemeyer et al., 1997; Engstrom et al., 2002). While many past measures were qualitative, extremely time consuming, and reserved for initiatives with a small number of participating communities, we have developed quantitative readiness measures that tap into the essential components of readiness and capacity for change (e.g., knowledge, support, expertise, leadership, and resource availability) at both the collaborative and community levels. In our research efforts, we found it extremely useful in identifying and demonstrating the variability that exists among communities in terms of readiness at the beginning of a community change initiatives, as well as documenting the varying trajectories of communities throughout the initiative.12 This is also the type of measure that provides an early warning sign that some communities may need technical assistance in order to move forward toward their goals of substance use reduction and positive community change. In past research, we also used other quantitative and qualitative data to provide more depth and context in explaining communities’ various trajectories in terms of their readiness for change. Finally, ICF has tailored readiness measures to the unique aspects of initiatives – each change effort is unique and while there are common elements to the concept of readiness, there are also unique aspects that need to be captured. In terms of analyses and alignment with the theory of change, grantee readiness for DFC implementation could be modeled as an important “input” variable – something communities bring with them at the start of the initiative. The measure we developed (and can adapt) for DFC collaborative readiness has 11 items (α=.86) while the community readiness measure has 5 items (α=.71).

Shared Vision and Cohesion

Another variable that has been empirically associated with collaborative effectiveness is the importance of establishing a shared vision, which is often one of the first steps in the strategic planning process, as well as a cohesive group that is able to articulate that vision with common language. Based on a search of the extant literature, we previously developed a measure with a small number of items which had adequate reliability (5 items, α=.87).

Perceived Effectiveness

Given the difficulty linking collaborative strategies and efforts directly to community and individual change, much of the past research on collaborative functioning has asked respondents about whether or not they perceived that their efforts made a difference in the issue they were addressing in their community. While it provides perceptual data, such a measure is one more link in the chain tying coalition efforts to community-level and individual-level change. Similar to the current items on collective self efficacy in the CCT, belief in the possibility of change due to coalition efforts is required before action and possible corresponding outcomes will result (Foster-Fishman, Cantillon, Pierce, & Van Egeren, 2007). However, in reviewing the CCT, we believe perceived effectiveness items, tailored to the goals of the DFC Program (e.g., increase protective factors, decrease risk factors, reduce youth substance use rates, increase collaborative capacity) would provide ONDCP with more valid and tailored information regarding coalition efforts. We have created such output measures in the past, tailoring items to the specific aspects of the change initiative, and established high reliability rates.

Sustainability

Another option is to include a more comprehensive measure of sustainability, particularly since it is one of the major elements of the SPF, yet not fully captured in the current CCT. Sustainability items are currently spread out in the CCT and the most direct item simply asks if the coalition chair thinks the collaborative will be around in ten years, along with a checklist of six items if they do not believe the collaborative will still be in existence. Sustainability is an important issue for DFC, and in order to assess this construct comprehensively we previously created a lengthy measure that looked at a number of areas of sustainability (e.g., sustainability of family involvement in the initiative). One of these components was sustainability of interagency collaboration with informal collaborative efforts, as well as the sustainability of a guiding collaborative body in the community post-funding (5 items, α= .74). We plan to work collaboratively with all stakeholders to augment and tailor this sustainability measure to DFC Programmatic efforts and accurately capture what elements communities will be able to sustain once Federal funding ends.

Inter-Organizational Coordination and Systems Change

Along with perceived effectiveness, we view inter-organizational coordination and systems change as two critical outcome variables that are currently not fully captured within the CCT. One of the main goals for DFC is to increase collaboration among community-based agencies, organizations, leaders, and residents. We feel these measures assess (a) whether or not collaboration and coordination has increased and (b) whether this coordination has resulted in meaningful community change corresponding to DFC goals. The inter-organizational measure is short yet reliable (4 items, α=.89) and has been utilized in a number of community-based collaborative change efforts (Allen, 2005; Nowell, 2009).

Contextual Variables

Another missing component from the current version of the CCT is a lack of neighborhood contextual assessments. Given the varied settings of DFC coalitions, we believe more needs to be done to capture the complexity of context, in order to correspond to DFC’s logic model and inform analyses. We propose adding variables that could greatly enhance the relevance of analyses as practitioners would be able to answer one of the most important questions regarding generalizability – “Would this work in my community?” Community social organization and collective efficacy are two variables that have been utilized extensively in community-based research and also reflect identified protective factors at the community level.

Finally, we will not limit our assessment of quality to measurement indices, but look for alternative methods to compile this critical information. For instance, quality can also be captured through the use of innovative methodologies that have rarely been applied to coalitions and community change efforts, such as social network analysis (Cross, Dickman, Newman-Gonchar, & Fagan, 2009; Nowell, 2009). This analytic technique allows researchers to understand not only which agencies and individuals interact to a greater degree, but also provide other characteristics, such as the depth of their collaboration and whether or not they are linked to the same players, in a similar deep and meaningful way (e.g., network density). To capture the multi-dimensional nature and quality of collaborative relationships, a number of indicators in network analysis can be included, such as communication frequency, responsiveness to concerns, trust in follow-through, legitimacy, and shared philosophy (Nowell, 2009). This type of analysis provides the necessary data to differentiate what leads to various collaborative outcomes (e.g., coordination outcomes versus community and systems change outcomes). This type of analysis may help identify whether the overall quality and depth of partnerships among key players, community members, and community-based organizations has reached a tipping point to produce meaningful community change. To decrease overall burden on DFC communities, we propose using this methodological approach with our case study communities13 using a valued-tie roster questionnaire process (Wasserman & Faust, 1994).

As discussed, we see changes – whether the addition or deletion of measures – to be a collaborative process among ONDCP, the evaluation team, and the Technical Advisory Group (TAG), which includes two DFC funded-coalition members. However, given the vast number of measures, we will initially offer some targeted constructs that could add value to analyses based on our past experience and review of the current CCT. Also, before any new measures are approved, the ICF team will assess response burden for these additional questions, as well as expected response burden for the entire data collection effort. We will aim to reduce the current response burden, as we want to ensure that prevention practitioners stay focused on their jobs and not on data collection requirements. We expect that making a good-faith effort to keep response burden down will also result in stronger buy-in for evaluation activities from coalition staff.14 Thus, while we plan on strengthening process data and attribution between process and outputs and outcomes, overall, we believe we can reduce burden for the staff of DFC coalitions.

In our experience, the assessment and planning phases are precisely where most grantees experience the greatest challenges. By providing measures to detect challenges before they become problems (e.g., lack of cooperation among coalition members), the ICF team will be able to provide evaluation data that ONDCP and its partners can use from the outset of each grant. Details on administering this readiness for change and implementation measure will be a point of discussion in the vetting process for the final measures.

Finally, the team will assess the need for the identification of “critical incidents” that could slow down or even stifle coalition development, such as (1) when changes in leadership took place, (2) when key partnerships were formed or fell apart, and (3) when major initiatives were implemented. Documentation of these incidents will serve two purposes:

By understanding what critical incidents took place, the evaluation team can provide context for each year’s evaluation results (e.g., “during this year, 29 coalition directorships changed hands”).

By documenting when these changes took place, we can model the effect of each type of critical incident on outcomes. For example, if major initiatives were implemented, did they have an effect on outcomes, and how long did it take for the incident to influence outcomes?

Together, these efforts will strengthen our evaluation results, and will allow ONDCP to share lessons learned with new grantees. In other words, we expect this effort to result in improved program administration, as well as an improved evaluation.

Objective 2: Refine Process Data with New Metrics on Coalition Operations

Following the refinement of process measures, we will be in a better position to develop summary metrics on coalition operations. This effort will involve both a review of the CCT, as well as the development of new dimensions to describe coalition operations and functioning. These new metrics can be used as covariates in outcome analyses or they can be descriptive metrics that stand on their own. These metrics are critical because they provide the path to testing more parsimonious, understandable, and powerful models of how coalitions operate and improve. They organize the many indicators of activity into principles or strategies for success.

The Coalition Classification Tool

Early in the study of coalitions promoting public health outcomes, researchers created models of coalition development and maturation (Florin et al., 1993; 2000). This stage-based developmental model is similar to other stage-based models, including the Community Coalition Action Theory (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002) and the stage-based typology that has largely driven DFC National Evaluation efforts to date. Overall, our past experiences have taught us that coalition development and capacity building is certainly stage-based, and that more “mature” coalitions tend to perform more effectively, but there is not one seminal theory that captures all the complexities of coalitions. The important practical knowledge related to stage-based development will include guidance on why more mature organizations are more effective, and what strategies or actions coalitions can take to reach and sustain higher stages. There is little consensus on answers to these questions, especially when coalitions encounter problems and cycle back a stage due to the continuous challenges that confront complex change efforts.

The existing CCT is in the tradition of these stage-based developmental models. It shares their basic underlying concepts, and to date it has not advanced answers to the why or how questions common to most stage-based typologies. It does, however, differ from prior measurement of stage-based development in its emphasis on basing assessment of stages on the degree to which coalitions have achieved capacity (as perceived by a key informant) in each of the five steps of the SPF across four functional areas. This incorporation of the SPF suggests the possibility of developing more useful guidance concerning what coalitions need to do to move forward. We will carefully assess the CCT to determine if closer analysis of resulting data, or slight revision to the instrument, may help achieve this contribution, which is necessary to the generation of lessons and useful information that is central to our analysis objectives.