Order 697

RM04-7-000 Final Rule.doc

FERC-919, [SIL component], Electric Rate Schedule Filings: Market Based Rates for Wholesale Sales of Electric Energy, Capacity and Ancillary Services by Public Utilities

Order 697

OMB: 1902-0234

Docket No.

RM04-7-000

119 FERC ¶ 61,295

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

18 CFR Part 35

(Docket No. RM04-7-000; Order No. 697)

Market-Based Rates For Wholesale Sales Of Electric Energy, Capacity And Ancillary Services By Public Utilities

(Issued June 21, 2007)

AGENCY: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

ACTION: Final Rule

SUMMARY: The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Commission) is amending its regulations to revise Subpart H to Part 35 of Title 18 of the Code of Federal Regulations governing market-based rates for public utilities pursuant to the Federal Power Act (FPA). The Commission is codifying and, in certain respects, revising its current standards for market-based rates for sales of electric energy, capacity, and ancillary services. The Commission is retaining several of the core elements of its current standards for granting market-based rates and revising them in certain respects. The Commission also adopts a number of reforms to streamline the administration of the market-based rate program.

EFFECTIVE DATE: This rule will become effective [Insert_Date60 days after publication in the FEDERAL REGISTER].

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Debra A. Dalton (Technical Information)

Office of Energy Markets and Reliability

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

888 First Street, N.E.

Washington, D.C. 20426

(202) 502-6253

Elizabeth Arnold (Legal Information)

Office of the General Counsel

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

888 First Street, N.E.

Washington, D.C. 20426

(202) 502-8818

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

Market-Based Rates For Wholesale Sales Of Electric Energy, Capacity And Ancillary Services By Public Utilities |

Docket No. |

RM04-7-000 |

ORDER NO. 697

FINAL RULE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paragraph Numbers

I. Introduction 1.

II. Background 7.

III. Overview of Final Rule 12.

IV. Discussion 33.

A. Horizontal Market Power 33.

1. Whether to Retain the Indicative Screens 33.

2. Indicative Market Share Screen Threshold Levels and Pivotal Supplier Application Period 80.

a. Market Share Threshold 82.

b. Pivotal Supplier Application Period 94.

3. DPT Criteria 96.

4. Other Products and Models 118.

5. Native Load Deduction 125.

a. Market Share Indicative Screen 125.

b. Pivotal Supplier Indicative Screen 143.

c. Clarification of Definition of Native Load 150.

d. Other Native Load Concerns 153.

6. Control and Commitment 156.

a. Presumption of Control 164.

b. Requirement for Sellers to have a Rate on File 212.

7. Relevant Geographic Market 215.

a. Default Relevant Geographic Market 215.

b. NERC’s Balancing Authority Area and Default Geographic Area 247.

c. Additional Guidelines for Alternative Geographic Market and Flexibility 253.

d. Specific Issues Related to Power Pools and SPP 279.

e. RTO/ISO Exemption 285.

8. Use of Historical Data 292.

9. Reporting Format 302.

10. Exemption for New Generation (Formerly Section 35.27(a) of the Commission’s Regulations) 307.

a. Elimination of Exemption in Section 35.27(a) 307.

b. Grandfathering 327.

c. Creation of a Safe Harbor 335.

11. Nameplate Capacity 339.

12. Transmission Imports 346.

a. Use of Historical Conditions and OASIS Practices 348.

b. Use of Total Transfer Capability (TTC) 363.

c. Accounting for Transmission Reservations 365.

d. Allocation of Transmission Imports based on Pro Rata Shares of Seller's Uncommitted Generation Capacity 370.

e. Miscellaneous Comments 376.

f. Required SIL Study for DPT Analysis 382.

13. Procedural Issues 387.

B. Vertical Market Power 397.

1. Transmission Market Power 400.

a. OATT Requirement 403.

b. OATT Violations and MBR Revocation 411.

c. Revocation of Affiliates’ MBR Authority 422.

2. Other Barriers to Entry 428.

3. Barriers Erected or Controlled by Other Than The Seller 452.

4. Planning and Expansion Efforts 454.

5. Monopsony Power 459.

C. Affiliate Abuse 464.

1. General Affiliate Terms and Conditions 464.

a. Codifying Affiliate Restrictions in Commission Regulations 464.

b. Definition of “Captive Customers” 469.

c. Definition of “Non-Regulated Power Sales Affiliate” 484.

d. Other Definitions 496.

e. Treating Merging Companies as Affiliates 499.

f. Treating Energy/Asset Managers as Affiliates 503.

g. Cooperatives 518.

2. Power Sales Restrictions 529.

3. Market-Based Rate Affiliate Restrictions (formerly Code of Conduct) for Affiliate Transactions Involving Power Sales and Brokering, Non-Power Goods and Services and Information Sharing 544.

a. Uniform Code of Conduct/Affiliate Restrictions - Generally 546.

b. Exceptions to the Independent Functioning Requirement 553.

c. Information Sharing Restrictions 570.

d. Definition of “Market Information” 590.

e. Sales of Non-Power Goods or Services 595.

f. Service Companies or Parent Companies Acting on Behalf of and for the Benefit of a Franchised Public Utility 599.

D. Mitigation 604.

1. Cost-Based Rate Methodology 606.

a. Sales of One Week or Less 606.

b. Sales of more than one week but less than one year 632.

c. Sales of one year or greater 658.

d. Alternative methods of mitigation 660.

2.Discounting 699.

3.Protecting Mitigated Markets 720.

a. Must Offer 720.

b. First-Tier Markets 776.

c. Sales that Sink in Unmitigated Markets 794.

d. Proposed Tariff Language 825.

E. Implementation Process 832.

1. Category 1 and 2 Sellers 836.

a. Establishment of Category 1 and 2 Sellers 836.

b. Threshold for Category 1 Sellers and Other Proposed Modifications 845.

2. Regional Review and Schedule 869.

F. MBR Tariff 897.

1. Tariff of General Applicability 901.

2. Placement of Terms and Conditions 925.

3. Single Corporate Tariff 928.

G. Legal Authority 938.

1. Whether Market-Based Rates Can Satisfy the Just and Reasonable Standard Under the FPA 938.

Consistency of Market-based Rate Program with FPA Filing Requirements 956.

2. Whether Existing Tariffs Must Be Found to Be Unjust and Unreasonable, and Whether the Commission Must Establish a Refund Effective Date 973.

H. Miscellaneous 976.

1. Waivers 976.

a. Accounting Waivers 980.

b. Timing 989.

c. Part 34 Waivers Blanket Authorizations 995.

2. Sellers Affiliated with a Foreign Utility 1001.

3. Change in Status 1009.

a. Fuel Supplies 1012.

b. Transmission Outages 1020.

c. Control 1028.

d. Triggering Events 1034.

e. Timing of Reporting 1036.

f. Sellers Affiliated with a Foreign Utility 1041.

4. Third-Party Providers of Ancillary Services 1047.

a. Internet Postings and Reporting Requirements 1053.

b. Pricing for Ancillary Services in RTOs/ISOs 1063.

5. Reactive Power and Real Power Losses 1073.

a. Reactive Power 1074.

b. Real Power Losses 1076.

V. Section-by-Section Analysis of Regulations 1078.

VI. Information Collection Statement 1106.

VII. Environmental Analysis 1125.

VIII. Regulatory Flexibility Act 1126.

IX. Document Availability 1130.

X. Effective Date and Congressional Notification 1133.

Appendix A: Standard Screen Format

Appendix B: Corporate Entities and Assets sample appendix

Appendix C: Required Provisions of the Market-Based Rate Tariff

Appendix D: Regions and Schedule for Regional Market power Update Process

Appendix E: List of Commenters and Acronyms

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

Before Commissioners: Joseph T. Kelliher, Chairman;

Suedeen G. Kelly, Marc Spitzer,

Philip D. Moeller, and Jon Wellinghoff.

Market-Based Rates For Wholesale Sales Of Electric Energy, Capacity And Ancillary Services By Public Utilities |

Docket No. |

RM04-7-000 |

FINAL RULE

ORDER NO. 697

(Issued June 21, 2007)

I.Introduction

On May 19, 2006, the Commission issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR), pursuant to sections 205 and 206 of the Federal Power Act (FPA),1 in which the Commission proposed to amend its regulations governing market-based rate authorizations for wholesale sales of electric energy, capacity and ancillary services by public utilities. In the NOPR, the Commission proposed to modify all existing market-based authorizations and tariffs so they would reflect any new requirements ultimately adopted in the Final Rule. After considering the comments received in response to the

NOPR, the Commission adopts in many respects the proposals contained in the NOPR, but with a number of modifications.

This Final Rule represents a major step in the Commission’s efforts to clarify and codify its market-based rate policy by providing a rigorous up-front analysis of whether market-based rates should be granted, including protective conditions and ongoing filing requirements in all market-based rate authorizations, and reinforcing its ongoing oversight of market-based rates. The specific components of this rule, in conjunction with other regulatory activities, are designed to ensure that market-based rates charged by public utilities are just and reasonable. There are three major aspects of the Commission’s market-based rate regulatory regime.

First is the analysis that is the subject of this rule: whether a market-based rate seller or any of its affiliates has market power in generation or transmission and, if so, whether such market power has been mitigated.2 If the seller is granted market-based rates, the authorization is conditioned on: affiliate restrictions governing transactions and conduct between power sales affiliates where one or more of those affiliates has captive customers; a requirement to file post-transaction electric quarterly reports (EQRs)

containing specific information about contracts and transactions; a requirement to file any change of status; and a requirement for all large sellers to file triennial updates.3

Second, for wholesale sellers that have market-based rate authority and sell into day ahead or real-time organized markets administered by Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) and Independent System Operators (ISOs), they do so subject to specific RTO/ISO market rules approved by the Commission and applicable to all market participants. These rules` are designed to help ensure that market power cannot be exercised in those organized markets and include additional protections (e.g., mitigation measures) where appropriate to ensure that prices in those markets are just and reasonable. Thus, a seller in such markets not only must have an authorization based on an analysis of that individual seller’s market power, but it must also abide by additional rules contained in the RTO/ISO tariffs.

Third, the Commission, through its ongoing oversight of market-based rate authorizations and market conditions, may take steps to address seller market power or modify rates. For example, based on its review of triennial market power updates required of market-based rate sellers, its review of EQR filings made by market-based rate sellers, and its review of required notices of change in status, the Commission may institute a section 206 proceeding to revoke a seller’s market-based rate authorization if it determines that the seller may have gained market power since its original market-based rate authorization. The Commission may also, based on its review of EQR filings or daily market price information, investigate a specific utility or anomalous market circumstances to determine whether there has been any conduct in violation of RTO/ISO market rules or Commission orders or tariffs, or any prohibited market manipulation, and take steps to remedy any violations. These steps could include, among other things, disgorgement of profits and refunds to customers if a seller is found to have violated Commission orders, tariffs or rules, or a civil penalty paid to the United States Treasury if a seller is found to have engaged in prohibited market manipulation or to have violated Commission orders, tariffs or rules.

The Commission recognizes that several recent court decisions by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit4 have created some uncertainty for sellers transacting pursuant to our market-based rate program. The cases raise issues with respect to the circumstances under which sellers’ pre-authorized market-based rate sales may be subject to retroactive refunds and the circumstances under which buyers might be able to invalidate or modify contracts based on the argument that the contracts were entered into at a time when markets were dysfunctional. The Commission’s first and foremost duty is to protect customers from unjust and unreasonable rates; however, we recognize that uncertainties regarding rate stability and contract sanctity can have a chilling effect on investments and a seller’s willingness to enter into long-term contracts and this, in turn, can harm customers in the long run. The Commission recently provided guidance in this regard, noting that these Ninth Circuit decisions addressed a unique set of facts and a market-based rate program that has undergone substantial improvement since 2001, and reiterating that an ex ante finding of the absence of market power, coupled with the EQR filing and effective regulatory oversight qualifies as sufficient prior review for market-based rate contracts to satisfy the notice and filing requirements of FPA section 205.5 Through this Final Rule, the Commission is clarifying and further improving its market-based rate program. Moreover, the Commission will explore ways to continue to improve its market-based rate program and processes to assure appropriate customer protections but at the same time provide greater regulatory and market certainty for sellers in light of the above court opinions

II.Background

In 1988, the Commission began considering proposals for market-based pricing of wholesale power sales. The Commission acted on market-based rate proposals filed by various wholesale suppliers on a case-by-case basis. Over the years, the Commission developed a four-prong analysis used to assess whether a seller should be granted market-based rate authority: (1) whether the seller and its affiliates lack, or have adequately mitigated, market power in generation; (2) whether the seller and its affiliates lack, or have adequately mitigated, market power in transmission; (3) whether the seller or its affiliates can erect other barriers to entry; and (4) whether there is evidence involving the seller or its affiliates that relates to affiliate abuse or reciprocal dealing.

The Commission initiated the instant rulemaking proceeding in April 2004 to consider “the adequacy of the current analysis and whether and how it should be modified to assure that prices for electric power being sold under market-based rates are just and reasonable under the Federal Power Act.”6 At that time, the Commission noted that much has changed in the industry since the four-prong analysis was first developed and posed a number of questions that would be explored through a series of technical conferences.

On April 14, 2004, the Commission issued an order modifying the then-existing generation market power analysis and its policy governing market power mitigation, on an interim basis.7 The April 14 Order adopted a policy that provided sellers a number of procedural options, including two indicative generation market power screens (an uncommitted pivotal supplier analysis and an uncommitted market share analysis), and the option of proposing mitigation tailored to the particular circumstances of the seller that would eliminate the ability to exercise market power. The order also explained that sellers could choose to adopt cost-based rates. On July 8, 2004, the Commission addressed requests for rehearing of the April 14 Order, reaffirming the basic analysis, but clarifying and modifying certain instructions for performing the generation market power analysis. Over the next year, the Commission convened four technical conferences, seeking input regarding all four prongs of the analysis.

On May 19, 2006, the Commission issued a NOPR in this proceeding.8 The Commission explained that refining and codifying effective standards for market-based rates would help customers by ensuring that they are protected from the exercise of market power and would also provide greater certainty to sellers seeking market-based rate authority.

The regulations proposed in the NOPR adopted in most respects the Commission’s existing standards for granting market-based rates, and proposed to streamline certain aspects of its filing requirements to reduce the administrative burdens on sellers, customers and the Commission. The Commission received over 100 comments and reply comments in response to the NOPR. A list of commenters is attached as Appendix E.

III.Overview of Final Rule

In this Final Rule, the Commission revises and codifies in the Commission’s regulations the standards for market-based rates for wholesale sales of electric energy, capacity and ancillary services. The Commission also adopts a number of reforms to streamline the administration of the market-based rate program. As set forth below, the Final Rule adopts in many respects the proposals contained in the NOPR, but with a number of modifications.

Horizontal Market Power

In this Final Rule, the Commission adopts, with certain modifications, two indicative market power screens (the uncommitted market share screen (with a 20 percent threshold) and the uncommitted pivotal supplier screen), each of which will serve as a cross check on the other to determine whether sellers may have market power and should be further examined. Sellers that fail either screen will be rebuttably presumed to have market power. However, such sellers will have full opportunity to present evidence (through the submission of a Delivered Price Test (DPT) analysis) demonstrating that, despite a screen failure, they do not have market power, and the Commission will continue to weigh both available economic capacity and economic capacity when analyzing market shares and Hirschman-Herfindahl Indices (HHIs).

With regard to control over generation capacity, the Commission finds that the determination of control is appropriately based on a review of the totality of circumstances on a fact-specific basis. No single factor or factors necessarily results in control. The Commission will require a seller to make an affirmative statement as to whether a contractual arrangement (energy management agreement, tolling agreement, specific contractual terms, etc.) transfers control and to identify the party or parties it believes controls the generation facility. Regarding a presumption of control, the Commission will continue its practice of attributing control to the owner absent a contractual agreement transferring such control, and we provide guidance as to how we will consider jointly-owned facilities.

The Commission adopts its current approach with regard to the default relevant geographic market, with some modifications. In particular, the Commission will continue to use a seller’s control area (balancing authority area)9 or the RTO/ISO market, as applicable, as the default relevant geographic market. However, where the Commission has made a specific finding that there is a submarket within an RTO, that submarket becomes the default relevant geographic market for sellers located within the submarket for purposes of the market-based rate analysis. The Commission also provides guidance as to the factors the Commission will consider in evaluating whether, in a particular case, to adopt an alternative geographic market instead of relying on the default geographic market.

The Commission modifies the native load proxy for the market share screens from the minimum peak day in the season to the average peak native load, averaged across all days in the season, and clarifies that native load can only include load attributable to native load customers based on the definition of native load commitment in § 33.3(d)(4)(i) of the Commission’s regulations. In addition, sellers are given the option of using seasonal capacity instead of nameplate capacity.

The Commission retains the snapshot in time approach based on historical data for both the indicative screens and the DPT analysis and disallows projections to that data. A standard reporting format is adopted for sellers to follow when summarizing their analysis.

The Commission modifies the treatment of newly-constructed generation and adopts an approach that requires all sellers to perform a horizontal analysis for the grant of market-based rate authority.

With regard to simultaneous transmission import limit studies (SILs), the Commission adopts the requirement that the SIL study be used as a basis for transmission access for both the indicative screens and the DPT analysis. Further, the Commission clarifies that the SIL study as shown in Appendix E of the April 14 Order is the only study that meets our requirements. The Commission provides guidance regarding how to perform the SIL study, including accounting for specific OASIS practices.

Finally, the Commission adopts procedures under which intervenors in section 205 proceedings may obtain expedited access to Critical Energy Infrastructure Information (CEII) or other information for which privileged treatment is sought.

Vertical Market Power

With regard to vertical market power and, in particular, transmission market power, the Commission continues the current policy under which an open access transmission tariff (OATT) is deemed to mitigate a seller’s transmission market power. However, in recognition of the fact that OATT violations may nonetheless occur, the Commission states that a finding of a nexus between the specific facts relating to the OATT violation and the entity’s market-based rate authority may subject the seller to revocation of its market-based rate authority or other remedies the Commission may deem appropriate, such as disgorgement of profits or civil penalties. In addition, the Commission creates a rebuttable presumption that all affiliates of a transmission provider should lose their market-based rate authority in each market in which their affiliated transmission provider loses its market-based rate authority as a result of an OATT violation.

With regard to other barriers to entry, the Commission adopts the NOPR proposal to consider a seller’s ability to erect other barriers to entry as part of the vertical market power analysis, but modifies the requirements when addressing other barriers to entry. The Commission also provides clarification regarding the information that a seller must provide with respect to other barriers to entry (including which inputs to electric power production the Commission will consider as other barriers to entry). The Commission adopts a rebuttable presumption that ownership or control of, or affiliation with an entity that owns or controls, intrastate natural gas transportation, intrastate natural gas storage or distribution facilities; sites for generation capacity development; and sources of coal supplies and the transportation of coal supplies such as barges and rail cars do not allow a seller to raise entry barriers, but intervenors are allowed to demonstrate otherwise. The Final Rule also requires a seller to provide a description of its ownership or control of, or affiliation with an entity that owns or controls, intrastate natural gas transportation, intrastate natural gas storage or distribution facilities; sites for generation capacity development; and sources of coal supplies and the transportation of coal supplies such as barges and rail cars. The Commission will require sellers to provide this description and to make an affirmative statement that they have not erected barriers to entry into the relevant market and will not erect barriers to entry into the relevant market. The Final Rule clarifies that the obligation in this regard applies both to the seller and its affiliates, but is limited to the geographic market(s) in which the seller is located.

Affiliate Abuse

With regard to affiliate abuse, the Commission adopts the NOPR proposal to discontinue considering affiliate abuse as a separate “prong” of the market-based rate analysis and instead to codify affiliate restrictions in the Commission’s regulations and address affiliate abuse by requiring that the provisions provided in the affiliate restrictions be satisfied on an ongoing basis as a condition of obtaining and retaining market-based rate authority. As codified in this Final Rule, the affiliate restrictions include a provision prohibiting power sales between a franchised public utility with captive customers and any market-regulated power sales affiliates10 without first receiving Commission authorization for the transaction under section 205 of the FPA. The Commission also codifies as part of the affiliate restrictions the requirements that previously have been known as the market-based rate “code of conduct” (governing the separation of functions, the sharing of market information, sales of non-power goods or services, and power brokering), as clarified and modified in this Final Rule. The Commission modifies certain of these provisions, including separation of functions and information sharing, consistent with certain requirements and exceptions contained in the Commission’s standards of conduct.11 In the Final Rule the Commission defines “captive customers” as “any wholesale or retail electric energy customers served under cost-based regulation” and provides clarification that the definition of “captive customers” does not include those customers who have retail choice, i.e., the ability to select a retail supplier based on the rates, terms and conditions of service offered. In addition, among other clarifications, the Commission clarifies and modifies the definition of “non-regulated power sales affiliate,” and changes the term to “market-regulated power sales affiliate.”

The Commission also provides clarification as to what types of affiliate transactions are permissible and the criteria used to make those decisions, and how the Commission will treat merging partners. In addition, the Commission codifies in the regulations a prohibition on the use of third-party entities, including energy/asset managers, to circumvent the affiliate restrictions, but does not adopt the NOPR proposal to treat energy/asset managers as affiliates. The Commission also provides clarification regarding the Commission’s market-based rate policies as they relate to cooperatives.

Mitigation

With regard to mitigation, in the Final Rule the Commission retains the incremental cost plus 10 percent methodology as the default mitigation for sales of one week or less; the default mitigation rate for mid-term sales (sales of more than one week but less than one year) priced at an embedded cost “up to” rate reflecting the costs of the unit(s) expected to provide the service; and the existing policy for sales of one year or more (long-term) sales.12 The Commission will continue to allow sellers to propose alternative cost-based methods of mitigation tailored to their particular circumstances. The Final Rule also states that the Commission will make its stacking methodology available for the public.13 In addition, the Commission will continue the practice of allowing discounting and will permit selective discounting by mitigated sellers provided that the sellers do not use such discounting to unduly discriminate or give undue preference.

The Commission concludes that use of the Western Systems Power Pool (WSPP) Agreement may be unjust, unreasonable or unduly discriminatory or preferential for certain sellers. Therefore, in an order being issued concurrently with this Final Rule, the Commission is instituting a proceeding under section 206 of the FPA to investigate whether, for sellers found to have market power or presumed to have market power in a particular market, the WSPP Agreement rate for coordination energy sales is just and reasonable in such market.

The Commission does not impose an across-the-board “must offer” requirement for mitigated sellers. While wholesale customer commenters have raised concerns relating to their ability to access needed power, the Commission concludes that there is insufficient record evidence to support instituting a generic “must offer” requirement.

The Commission limits mitigation to the market in which the seller has been found to possess, or chosen not to rebut the presumption of, market power and does not place limitations on a mitigated seller’s ability to sell at market-based rates in areas in which the seller has not been found to have market power.

Finally, regarding mitigation, the Final Rule allows mitigated sellers to make market-based rate sales at the metered boundary between a mitigated balancing authority area and a balancing authority area in which the seller has market-based rate authority under the conditions set forth herein, including a record retention requirement, and provides a tariff provision to allow for such sales.

Implementation Process

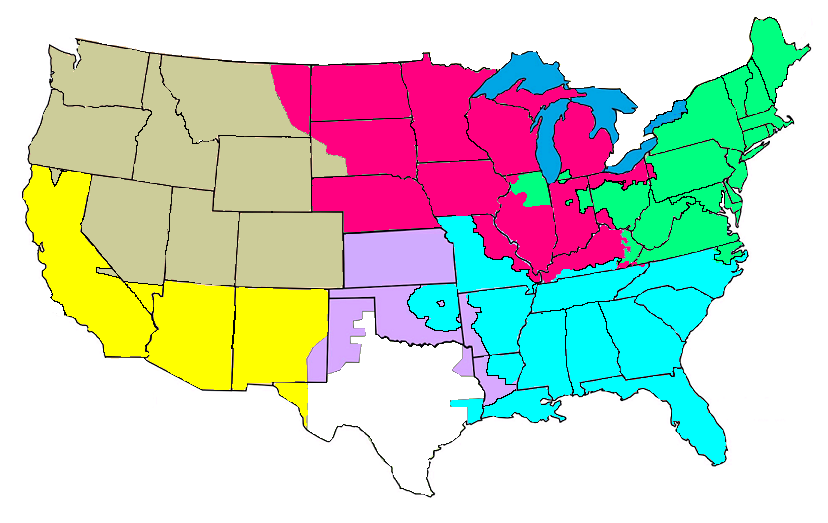

The Commission adopts the NOPR proposal to create a category of sellers (Category 1 sellers) that are exempt from the requirement to automatically submit updated market power analyses, with certain clarifications and modifications. In addition, the Commission adopts the NOPR proposal to implement a regional approach to updated market power analyses, but reduces the number of regions from nine to six.

As for a standardized tariff, the Commission does not adopt the NOPR proposal to adopt a market-based rate tariff of general applicability that all market-based rate sellers will be required to file as a condition of market-based rate authority and to require each corporate family to have only one tariff, with all affiliates with market-based rate authority separately identified in the tariff. Instead, the Commission adopts specific market-based rate tariff provisions that the Commission will require to be part of a seller’s market-based rate tariff. However, the Commission will allow a seller to include seller specific terms and conditions in its market-based rate tariff, but the Commission will not review any of these provisions, as they are presumed to be just and reasonable based on the Commission’s finding that the seller and its affiliates lack or have adequately mitigated market power in the relevant market.

Miscellaneous Issues

The Commission also provides clarifications in the Final Rule with regard to accounting waivers, Part 34 blanket authorizations, sellers affiliated with foreign entities, and the change in status reporting requirement. Further, the Commission abandons the posting requirements for third party sellers of ancillary services at market-based rates as redundant of other reporting requirements.

IV.Discussion

A.Horizontal Market Power

1.Whether to Retain the Indicative Screens

As discussed in detail below, the Commission is adopting in this Final Rule two indicative horizontal market power screens, each of which will serve as a cross-check on the other to determine whether sellers may have market power and should be further examined. Although some sellers disagree with the use of two screens or find flaws in them, we conclude that this conservative approach will allow the Commission to more readily identify potential market power. Sellers that fail either screen will be rebuttably presumed to have market power. However, such sellers will have full opportunity to present evidence (through the submission of a DPT analysis) demonstrating that, despite a screen failure, they do not have market power. No screen is perfect, but we believe this approach appropriately balances the need to protect against market power with the desire not to place unnecessary filing burdens on utilities.

The first screen is the wholesale market share screen, which measures for each of the four seasons whether a seller has a dominant position in the market based on the

number of megawatts of uncommitted capacity owned or controlled by the seller as compared to the uncommitted capacity of the entire relevant market.14

The second screen is the pivotal supplier screen, which evaluates the potential of a seller to exercise market power based on uncommitted capacity at the time of the balancing authority area’s annual peak demand. This screen focuses on the seller’s ability to exercise market power unilaterally. It examines whether the market demand can be met absent the seller during peak times. A seller is pivotal if demand cannot be met without some contribution of supply by the seller or its affiliates.15

Use of the two screens together enables the Commission to measure market power at both peak and off-peak times, and to examine the seller’s ability to exercise market power unilaterally and in coordinated interaction with other sellers. Use of the two

screens, therefore, provides a more complete picture of a seller’s ability to exercise market power.16

As discussed more fully in the following sections, with regard to determining the total supply in the relevant market, the horizontal market power analysis centers on and examines the balancing authority area where the seller’s generation is physically located. Total supply is determined by adding the total amount of uncommitted capacity located in the relevant market (including capacity owned by the seller and competing suppliers) with that of uncommitted supplies that can be imported (limited by simultaneous transmission import capability) into the relevant market from the first-tier markets.

Uncommitted capacity is determined by adding the total nameplate or seasonal capacity17 of generation owned or controlled through contract and firm purchases, less operating reserves, native load commitments and long-term firm sales.18 Uncommitted capacity from a seller’s remote generation (generation located in an adjoining balancing authority area) should be included in the seller’s total uncommitted capacity amounts. Any simultaneous transmission import capability should first be allocated to the seller’s uncommitted remote generation. Any remaining simultaneous transmission import capability would then be allocated to any uncommitted competing supplies.

Capacity reductions as a result of operating reserve requirements should be no higher than State and Regional Reliability Council operating requirements for reliability (i.e., operating reserves). Any proposed amounts that are higher than such requirements must be fully supported and will be considered on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, if an intervenor provides conclusive evidence that a seller did not in actual practice comply with the NERC or regional reliability council operating reserve requirements, then we will take this into account in determining the amount of the operating reserve deduction. However, we emphasize that we expect each utility to meet its NERC and regional reliability council reserve requirements, and that absent a clear showing to the contrary by an intervenor, the required operating reserve requirement is what we will use as the deduction in the market-based rate calculation.19

The Commission does not expect that sellers will have planned generation outages scheduled for the annual peak load day. However, on a case-by-case basis, the Commission will consider credible evidence that planned generation outages for the peak load day of the year should be included based on the particular circumstances of the seller.20

With regard to the pivotal supplier analysis, after computing the total uncommitted supply available to serve the relevant market, the next step in this analysis involves identifying the wholesale market. The proxy for the wholesale load is the annual peak load (needle peak) less the proxy for native load obligation (i.e., the average of the daily native load peaks during the month in which the annual peak load day occurs). Peak load is the largest electric power requirement (based on net energy for load) during a specific period of time usually integrated over one clock hour and expressed in megawatts, for the native load and firm wholesale requirements sales.

To calculate the net uncommitted supply available to compete at wholesale, the pivotal supplier analysis deducts the wholesale load from the total uncommitted supply. If the seller’s uncommitted capacity is less than the net uncommitted supply, the seller satisfies the pivotal supplier portion of the generation market power analysis and passes the screen. If the seller’s uncommitted capacity is equal to or greater than the net uncommitted supply, then the seller fails the pivotal supplier analysis which creates a rebuttable presumption of market power.

With regard to the wholesale market share analysis, which measures for each of the four seasons whether a seller has a dominant position in the market based on the number of megawatts of uncommitted capacity owned or controlled by the seller as compared to the uncommitted capacity of the entire relevant market, uncommitted capacity amounts are used, as described above, with the following variation. Planned outages (that were done in accordance with good utility practice) for each season will be considered. Planned outage amounts should be consistent with those as reported in FERC Form No. 714. To determine the amount of planned outages for a given season, the total number of MW-days of outages is divided by the total number of days in the season. For example, if 500 MW of generation that is out for six days during the winter period the calculation of planned outages would be: (500 MW X 6)/91 or 33 MW.

The market share analysis adopts an initial threshold of 20 percent. That is, a seller who has less than a 20 percent market share in the relevant market for all seasons will be considered to satisfy the market share analysis.21 A seller with a market share of 20 percent or more in the relevant market for any season will have a rebuttable presumption of market power but can present historical evidence to show that the seller satisfies our generation market power concerns.

Commission Proposal

In the NOPR, the Commission proposed to retain the indicative screens (pivotal supplier and market share) to assess horizontal market power that were initially adopted in April 2004.22 Because the indicative screens are intended only to identify the sellers that require further review, the Commission proposed to retain the 20 percent threshold for the wholesale market share indicative screen, stating that the 20 percent market share threshold strikes the right balance in seeking to avoid both “false negatives” and “false positives.” The Commission also proposed to continue to measure pivotal suppliers at the time of the annual peak load in the pivotal supplier indicative screen, which is the most likely point in time that a seller will be a pivotal supplier. For this reason, the Commission did not propose to expand the pivotal supplier analysis to other time periods.

Comments

Numerous commenters question whether the Commission should retain the current indicative screens in whole or in part. For example, Southern, Duke and EEI advocate abandoning the market share indicative screen altogether. They argue that the market share indicative screen is “fatally flawed” because it does not take into account wholesale demand in the relevant market23 which makes it difficult for traditional utilities outside of RTOs/ISOs to pass.24 E.ON. US. and PNM/Tucson separately argue that one must consider the level of demand that is seeking supply and, more particularly, what ability sellers have to exercise market power over those buyers.25 In this regard, E.ON. US. and PNM/Tucson argue that to the extent the market share screen does not consider wholesale demand, it is not a useful indicator, and in fact is almost universally a false indicator of the ability of a seller to exercise market power over demand. Also, EEI argues that because of design flaws inherent in the market share screen as well as the negative impact that the use of this test has had since 2004 on the development of competitive wholesale markets (through the inappropriate exclusion of the majority of non-RTO utilities from participating in that market), the market share screen should be eliminated for all market power screening and analysis purposes.26

EEI contends that the Commission should use only the pivotal supplier screen for indicative screening purposes and the DPT pivotal supplier and market concentration analyses for the purposes of rebutting the presumption of generation market power that would result from the failure of the indicative pivotal supplier screen. EEI argues that if the Commission continues to use the market share screen as an initial screen, the Commission should not include a market share test as a component of any subsequent DPT analysis of market power.

E.ON U.S. and PNM/Tucson generally agree, stating that market share is an unreliable measure of market power in competitive energy markets and that the courts have long recognized that market share is not a reliable indicator of market power in regulated markets.27 In particular, E.ON U.S. and PNM/Tucson argue that even a marginal failure of the market share screen results in a rebuttable presumption of market power that has tremendous consequences by forcing sellers to proceed to costly and time-consuming DPT analysis or agree to mitigation. As a result, the “false positives” arising from the market share screen dampen the vigor of competitive wholesale market participation by unnecessarily curtailing the market-based authority of entities that, in fact, lack market power (to the extent such entities choose not to pursue a costly and uncertain effort to rebut the presumption of market power created by the screen failure).28

Duke and Southern suggest that a wholesale contestable load analysis (also described as a "competitive alternatives" analysis)29 should be added to the indicative screens, which would consider the amount of excess market supply available to serve the amount of wholesale demand seeking supply.30 Generally, if available non-applicant supply is at least twice the contestable load, advocates of the contestable load analysis believe that is sufficient to make a finding that the market is competitive.31 Other commenters agree that the market share indicative screen can diminish competition because sellers that are subjects of a FPA section 206 investigation tend to choose mitigation rather than challenge the presumption of market power.32

Duke argues that the Commission has yet to establish a need for using the market share indicative screen in addition to the pivotal supplier indicative screen in assessing the potential for the exercise of generation market power. In this regard, Duke argues that the Commission itself acknowledged in the April 14 Order (establishing the new indicative market power screens) that if a supplier passes the pivotal supplier indicative screen, it would not be able to exercise generation market power. Thus, Duke concludes that the use of any other indicative screens would appear to be redundant and an unwarranted burden on market-based rate sellers. 33 Further, Duke submits that neither of the rationales originally cited by the Commission in support of the market share screen – its ability to identify “coordinating behavior,” or its ability to detect the exercise of market power in off-peak periods – has been validated. In this regard, Duke submits that the potential for “coordinating behavior” should consider overall market concentration levels as measured by HHIs and in any event, such behavior is already subject to oversight and substantial penalties under the antitrust laws and the Commission’s recently adopted rule prohibiting market manipulation. Further, Duke claims that the nearly universal failure rate of load-serving utilities under the market share indicative screen in their control areas underscores its limited value as an indicator of off-peak market power.34

Duke states that a review of filings by vertically integrated utilities that are not RTO participants shows that the vast majority have failed the market share screen in their control areas, and most have subsequently been forced to adopt some form of cost-based mitigation for wholesale sales in that market. Yet Duke is unaware of any credible evidence suggesting that any form of generation market power has been exercised by these utilities. Instead, Duke states that the Commission has revoked market-based rate authority and imposed mitigation on the basis of indicative screen results that suggest the potential for market power.35 APPA/TAPS counter that the Commission should not limit its response to market power only to instances of its actual exercise; they note that the Commission considers whether a seller and its affiliates have market power or have mitigated it, not whether it has been exercised.36

Another commenter suggests substituting the HHI for the market share indicative screen or supplementing the indicative screens with the HHI, reasoning that the market must be evaluated, not just the individual market share.37

Southern states that the Commission should rely upon any indicative screens only in conjunction with an optional “expedited track” safe harbor review. Under Southern’s proposal, the indicative screens would be voluntary and those submitting to and passing the screens would be permitted to retain or obtain market-based rate authority, subject to a proceeding under section 206 of the FPA, under which the party seeking to challenge the rate must submit substantial evidence justifying revocation. If a seller fails the screen(s), or if it elects to submit a DPT rather than voluntarily submit the indicative screens, then a robust market power assessment should be used to determine whether (or the extent to which) the seller should be permitted to sell power at market-based rates.

In Southern’s view, failure of the indicative screens should not give rise to a presumption of market power.38 Southern argues that mere failure to pass a screen, without more robust market power assessments, is an insufficient basis upon which to base a presumption of market power. Southern argues this is because, in the case of the pivotal supplier screen, the Commission itself admits that it does not give a full picture and that the DPT provides better information. With regard to the market share screen, Southern argues that the market share screen has even more basic problems as an indicator of market power. Southern states that, because of the market share analysis’ serious flaws, the great majority of integrated franchised public utilities inevitably will fail the market share screen. Thus, with respect to integrated franchised public utilities, the market share screen serves no real purpose other than to state the obvious: integrated franchised public utilities build and maintain adequate resources to serve their native loads and inevitably will have market shares greater than 20 percent in their home control areas under the Commission’s computational procedures. Southern states that, since the DPT reduces the level of false positives and is a more definitive means for determining the existence of market power, the Commission should use the DPT as the default test.39 PPL agrees with Southern's proposal that the indicative screens be made voluntary.40

Southern states that if the market share screen is retained, it should be adjusted for forced outages because such capacity is not available. Southern also notes that forced outages are tracked and reported to the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), which presents generating unit availability statistics data for generator unit groups.41

NRECA disagrees with Southern’s proposal, stating that forced outage deductions have little effect when applied to all sellers.42 It also believes that sellers do not make forced outage deductions in long-term contracts; therefore, it is inappropriate to make the deduction for the market power tests.

While EPSA does not agree with some of the Commission’s proposed changes to the horizontal analysis in the NOPR (i.e., changes to the post-1996 exemption and the native load proxy), in general, EPSA supports the two indicative screens as a means for indicating that an entity might have market power.

EPSA notes that it is time to move beyond the battle over crafting the perfect screens, arguing: 1) it is likely no such perfect screens exist, as evidenced by the fact that stakeholders and the Commission have gone through several iterations to get to today’s screens; and 2) in the end, the screens are only indicative measures. EPSA notes that failure of one or both of the screens does not brandish an entity with market power, but merely raises a flag that further analysis is necessary in order to assess an entity’s ability to exercise market power. The current state of wholesale electricity markets, EPSA argues, requires indicative screens that are neither definitive nor an aperture letting everything pass, but rather a sieve that catches potential problems for further examination. EPSA agrees with retention of both of the current indicative screens and the “next steps” set forth for those entities that fail one or both of those screens.

Several other commenters also support retention of the indicative screens. Some of these commenters state that, because section 205 of the FPA requires rates to be just and reasonable, a market share indicative screen is appropriate to ensure that outcome. NRECA adds that “[b]ecause of past or present state regulation, many traditional public utilities have acquired dominant market shares of generation capacity in their own control areas—sufficient to enable them to exercise market power absent regulation of their behavior. NRECA submits that regardless of the cause the incumbent public utilities will remain the dominant firms in their own control areas absent significant new market entry in the form of new generation construction in the control area by independent firms, or significant transmission construction to permit entry by generation outside the control area. Morgan Stanley also favors retaining the market share indicative screen, noting that failure of the market share indicative screen does not mean the process is unfair, and asserting that exclusive reliance on the pivotal supplier indicative screen may compromise market power detection.43

With regard to the suggestion that the Commission adopt a contestable load analysis, several commenters criticize the contestable load analysis, stating that it changes the focus of the market power analysis from the seller to the market. They counter that the contestable load analysis is unsound, with APPA/TAPS citing Federal

Trade Commission (FTC) comments in this proceeding that such an analysis is flawed.44 NRECA states that commenters have not provided sufficient justification for using a contestable load analysis.

With regard to Southern's suggestion that the indicative screens be made voluntary and function as a safe harbor, such that screen failure would simply mean that further review of the seller would be appropriate, but not merit a section 206 investigation, NRECA states that Southern's argument is contrary to law. NRECA argues that, as the proponent of a tariff allowing it to charge market-based rates, the public utility has the burden of proof to demonstrate that its wholesale rates will be disciplined by competition. NRECA submits that failing the indicative screens indicates that the seller has not yet provided "'empirical proof'" that competition will drive down prices to just and reasonable levels as the FPA requires.45

Commission Determination

We adopt the proposal in the NOPR to retain both of the indicative screens. The intent of the indicative screens is to identify the sellers that raise no horizontal market power concerns and can otherwise be considered for market-based rate authority. At the same time, sellers that do not pass the indicative screens are allowed to provide additional analysis for Commission consideration. Because the indicative screens are intended to screen out only those sellers that raise no horizontal market power concerns, as opposed to other sellers that raise concerns but may not necessarily possess horizontal market power, we find it appropriate to use conservative criteria and to rely on more than one screen. A conservative approach at the indicative screen stage of the proceeding is warranted because, if a seller passes both of the indicative screens, there is a rebuttable presumption that it does not possess horizontal market power.

The rebuttable presumption of horizontal market power that attaches to sellers failing one of the indicative screens is just that—a rebuttable presumption. It is not a definitive finding by the Commission; sellers are provided with several procedural options including the right to challenge the market power presumption by submitting a DPT analysis, or, alternatively, sellers can accept the presumption of market power and adopt some form of cost-based mitigation.46 Accordingly, we will adopt the proposal to continue to use the two indicative screens and find that failure of either indicative screen creates a rebuttable presumption of market power. We reiterate our finding that "[f]ailure to pass either of the indicative screens . . . will constitute a prima facie showing that the rates charged by the seller pursuant to its market-based rate authority may have become unjust and unreasonable and that continuation of the seller’s market-based rate authority may no longer be just and reasonable."47

This approach, contrary to the claims of several commenters, will help to further competitive markets by allowing sellers without market power to sell power at market-based rates, and it will similarly give customers security that sellers that fail the screens are required to submit to further scrutiny and/or mitigation.

The pivotal supplier and market share indicative screens measure different aspects of market power. As the Commission stated in the April 14 Order, the uncommitted pivotal supplier indicative screen measures the ability of a firm to dominate the market at peak periods. The uncommitted market share analysis provides a measure as to whether a supplier may have a dominant position in the market, which is another indicator of potential unilateral market power and the ability of a seller to effect coordinated interaction with other sellers. The market share screen is also useful in measuring market power because it measures a seller’s size relative to others in the market, in particular, the seller’s share of generating capacity uncommitted after accounting for its obligations to serve native load. The market share screen provides a snapshot of these market shares in each season of the year. Taken together, the indicative screens can measure a seller's market power at both peak and off-peak times.48 Both market share and pivotal supplier indicative screens are appropriate first steps for the Commission to use in determining if it needs a more robust analysis to determine whether the seller has market power. We conclude that having two screens as backstops to one another will better assist us in determining the existence of potential market power. Accordingly, we reject the suggestion of several commenters to abandon the market share indicative screen. We will retain both the pivotal supplier and market share indicative screens as described in the NOPR, as well as apply the rebuttable presumption of market power for those sellers that fail either indicative screen.49

In addition, the Commission will not adopt suggestions to alter the indicative screens in order to incorporate a contestable load analysis, as proposed by EEI and others. As noted by the FTC, APPA/TAPS, and NRECA, the contestable load analysis is flawed because, among other things, it does not consider control of generation through contracts. The Commission explained in the April 14 Order that the roles of the indicative screens are meant to be complementary. The pivotal supplier indicative screen indicates whether demand can be met without some contribution of supply by the seller at peak times, while the market share indicative screen indicates whether the seller has a dominant position in the market and may therefore have the ability to exercise horizontal market power, both unilaterally and in coordination with other sellers. 50 The contestable load analysis is essentially a variant on the pivotal supplier screen with differences in the calculation of wholesale load and the test thresholds, because, like the pivotal supplier screen, it addresses whether suppliers other than the seller can meet the demand in the relevant market. Therefore incorporating such an analysis would not improve our ability to establish a presumption of whether a seller has market power. The contestable load analysis therefore would add little useful information, and without the market share indicative screen, the Commission would have insufficient information because there would be no analysis of a seller’s size relative to the other sellers in the market, and no information on the seller's market power during off-peak periods.

In addition, the contestable load analysis fails to consider the relative price of the competing supplies. Commenters have argued that if available non-applicant supply is at least twice the contestable load, the market is competitive. However, this analysis fails to consider whether the available non-applicant supply is competitively priced and, thus, in the market. This weakness in the contestable load analysis is addressed in the DPT analysis which considers only supply that is competitively priced.

We also reject arguments by E.ON U.S. and PNM/Tucson that the wholesale market share screen should be replaced because, they argue, it does not consider the size of the wholesale supply in the relevant market relative to the wholesale demand in that market. E.ON. U.S. and PNM/Tucson are requesting an analysis very similar to the contestable load analysis, whose defining characteristic is measuring the wholesale supply market relative to wholesale demand, which, as stated above, is essentially the same as the pivotal supplier screen, and would therefore add little useful information to the screening process.

We reject Duke’s claim that because neither of the rationales originally cited by the Commission in support of the market share indicative screen – its ability to identify “coordinating behavior,” or its ability to detect the exercise of market power in off-peak periods – has been validated, the wholesale market share indicative screen is unnecessary. Specifically, the Commission believes that the ability of market participants to exercise market power through "coordinating behavior" is a legitimate concern under the FPA, in addition to the fact that it has long been recognized by the antitrust authorities.51 The Commission also believes it is possible to exercise market power in off-peak periods because during such times the amount of supply in the market may be greatly reduced (e.g., because of planned outages for plant maintenance), meaning that a seller that is not dominant at peak times might be at off-peak.

Moreover, we agree with APPA/TAPS that market-based rate assessments are used to determine the ability to exercise, not the exercise of, market power. The Commission need not wait passively until market power is exercised. Rather, it is incumbent on the Commission to set policies that will ensure that rates remain just and reasonable under section 205 of the FPA. Requiring sellers to submit screens that analyze the sellers’ potential to exercise market power is consistent with such a policy.

We are unpersuaded by E.ON U.S.’s and PNM/Tucson's argument that “false positives” arising from the market share screen dampen the vigor of competitive wholesale market participation by unnecessarily curtailing the market-based rate authority of entities that, according to E. ON. U.S. and PNM/Tucson, lack market power. We recognize that a conservative screen may result in some false positives, but must weigh that against the cost of the false negatives that would occur if we adopted a less conservative screen or eliminated the market share indicative screen.

E.ON U.S. and PNM/Tucson, to support their point, cite several court cases in which market shares were alleged not to be reliable indicators of market power in regulated markets. However, the cases cited are not relevant to the issue of whether the Commission should retain the wholesale market share screen. The purpose of our indicative screens is to distinguish sellers that may raise horizontal market power concerns and those that do not; the market share screen is not the end of our horizontal

market power analysis. In contrast, the cases cited by E.ON U.S. and PNM/Tucson52 involve allegations of unlawful restraint of trade in violation of the Sherman Act,53 a federal antitrust statute prohibiting trade monopolies. The focus in such cases (whether a company has violated the Sherman Act) and the standard for making such a determination is different than the focus of the Commission at the indicative screen stage of the horizontal market power analysis (identifying sellers that require further horizontal market analysis without making a definitive finding regarding market power).

On both theoretical and practical grounds, we reject the argument by EEI and others that the market share indicative screen can diminish competition because some sellers that are the subject of a section 206 investigation choose mitigation rather than challenge the presumption of market power. First, mitigating a seller with market power ensures that the other sellers in the market cannot benefit from an artificially high market price due to the seller with market power exercising market power. Second, in our experience, sellers that choose mitigation rather than challenge the presumption of market power have market shares that are likely to indicate a dominant position in a geographic market.54 In addition, many sellers have successfully rebutted the presumption of market power after failing one of the indicative screens.55

Further, we will not adopt the suggestion to substitute the HHI for the market share indicative screen or to supplement the indicative screens with the HHI. The indicative screens are used to separate sellers who are presumed to have market power from those that, absent extraordinary and transitory circumstances, clearly do not. We will not substitute the market share screen with an HHI screen because, as we have stated above, the seller’s market share conveys useful information about its ability to exercise market power, so eliminating the market share screen in favor of the HHI could increase the risk of false negatives.56 In addition, a high HHI can be the result of high market shares of sellers in the market other than the seller, and the focus of our analysis is on the sellert’s ability to exercise market power, so the HHI would provide little additional information to allow us to identify those sellers who clearly do not have market power. Finally, the HHI primarily provides information on the ability of sellers to exercise market power through coordinated behavior, while the market share screen primarily provides information on a particular seller’s ability unilaterally to exercise market power. We will not supplement the indicative screens with the HHI screen because the indicative screens are sufficiently conservative to identify those sellers that have a rebuttable presumption of market power, without having to add an additional layer of review at the initial stage.

We clarify that sellers and intervenors may present alternative evidence such as a DPT study or historical sales and transmission data to support or rebut the results of the indicative screens. For example, intervenors could present evidence based on historical wholesale sales data or challenge the assumption that competing suppliers inside a balancing authority area have access to the market (such a challenge could take into account both the actual historical transmission usage at the time of the study as well as the amount of available transmission capacity at that time).57 A seller may present evidence in support of a contention that, notwithstanding the results of the indicative screens, it does not possess market power.58 However, sellers should not expect that the Commission will postpone initiating a section 206 investigation to protect customers

while it examines this supplemental information if screen failures are indicated.59 Nevertheless, the Commission may factor in this alternative evidence before deciding whether to initiate a section 206 investigation if the alternative evidence is appropriately supported, comprehensive and unambiguous, and conducive to prompt review by the Commission.

We will not adopt Southern's suggestion that the indicative screens be made voluntary. We will continue to require that sellers submit the indicative screens or concede the presumption of market power before they file a DPT. However, as discussed above, a seller may submit with its indicative screens a DPT as alternative evidence. As stated above, submission of a DPT analysis as alternative evidence at the same time a seller submits the indicative screens may result in the Commission instituting a section 206 proceeding to protect customers, based on failure of an indicative screen, while the Commission considers the merits of the DPT analysis.

We do not agree with Southern’s view that failure of the indicative screen(s) does not provide a sufficient basis to establish a rebuttable presumption of market power. The indicative screens are intended to identify the sellers that raise no horizontal market power concerns and can otherwise be considered for market-based rate authority. Sellers failing one or both of the indicative screens, on the other hand, are identified as sellers that potentially possess horizontal market power and for which a more robust analysis is required. The uncommitted pivotal supplier screen focuses on the ability to exercise market power unilaterally. Failure of this screen indicates that some or all of the seller’s generation must run to meet peak load. The uncommitted market share analysis indicates whether a supplier has a dominant position in the market. Failure of the uncommitted market share screen may indicate the seller has unilateral market power and may also indicate the presence of the ability to facilitate coordinated interaction with other sellers. It is on this basis that we find that a rebuttable presumption of market power is warranted when a seller fails one or both of the indicative screens. However, we agree with Southern that the DPT is a more definitive means for determining the existence of market power. As a result, we allow sellers that have failed one or both of the indicative screens to rebut the presumption of market power by performing the DPT. Further, because failure of one or both of the indicative screens only creates a rebuttable presumption of market power and sellers have a Commission-endorsed analysis that they can use to rebut that presumption (the DPT), we find without merit Southern’s view that the indicative screens create a priori evidentiary presumption of guilt, are improper, and create due process concerns.

With regard to Southern’s suggestion that we use the DPT as the default test, we find that if we were to do so our ability to protect customers while the analysis is evaluated could be compromised. The DPT is a more involved and complex analysis. The Commission has also at times set a DPT analysis for evidentiary hearing which greatly extends the time between when the DPT is submitted to the Commission and when a final decision is rendered. The rates customers are subject to during the time period before the issuance of a Commission order addressing a seller’s DPT would not be subject to refund and, accordingly, the customers would be unprotected if the seller ultimately is found to have market power. However, under our current policy, and as adopted herein, if a seller wishes to file a DPT rather than the indicative screens it may do so. In doing so, the seller concedes that it fails the indicative screens, which concession establishes a rebuttable presumption of market power, and the Commission will issue an order initiating a section 206 proceeding to investigate whether the seller has market power and establishing a refund effective date for the protection of customers while the Commission evaluates the filed DPT. In the case of a seller that concedes the failure of one or both of the screens and submits the DPT in the same filing, the Commission is able to establish a refund effective date at an earlier time than if the seller were able to skip the screen stage entirely and file a DPT without conceding a screen failure.

We will reject Southern's request that forced outages be deducted from capacity. As we stated in the July 8 Order, "forced outages are non-recurring events that do not reflect normal operating conditions."60 Allowing deduction of forced outages will generally not change indicative screen results, because all sellers will be able to deduct forced outages, offsetting each other. In the unlikely event that forced outage numbers were not completely offsetting, allowing forced outages in the indicative screens would benefit owners of relatively unreliable fleets at the expense of owners of relatively reliable fleets.

2.Indicative Market Share Screen Threshold Levels and Pivotal Supplier Application Period

Commission Proposal

In the NOPR, the Commission proposed to retain the 20 percent threshold for the wholesale market share screen (i.e., with a market share of less than 20 percent, the seller would pass the screen). The Commission stated that since the screens are indicative, not definitive, a relatively conservative threshold for passing them was appropriate. Indeed, pursuant to the horizontal market power analysis, the Commission will not make a definitive finding that a seller has market power unless and until the more robust analysis, the DPT, is considered.

The Commission proposed to continue the use of annual peak load in the pivotal supplier analysis and not to expand the pivotal supplier analysis to include monthly assessments. It stated that the pivotal supplier analysis examines the seller’s market power during the annual peak, and that the hours near that point in time are the most likely times that a seller will be a pivotal supplier.

a.Market Share Threshold

Comments

A number of commenters argue that 20 percent is too low a threshold for the market share indicative screen. Some point out that, given native load requirements, it is very difficult for investor-owned utilities outside of RTOs/ISOs to fall below the 20 percent threshold for the market share indicative screen.61 Duke also notes that the 20 percent criterion is incompatible with regional planning requirements because, according to Duke, the amount of capacity needed to satisfy regional planning reserve margins "would place the utility at substantial risk of exceeding the 20 percent threshold."62

E.ON U.S. argues that, because the courts have not considered a 20 percent market share to indicate a market power concern, associating a market share indicative screen failure with a presumption of market power is inappropriate.63 Additionally, Progress Energy argues that it is inappropriate to associate failure of the market share screen with a presumption of market power when U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) merger guidelines state that only firms with 35 percent or more market share have market power.64

PPL states that it agrees that the 20 percent threshold should be replaced by a 35 percent threshold in the market share screen and argues that such an increase will avoid the false-positive failure rate of the indicative screens, and the cost, time and repercussions in the financial markets of the extended pendency of a market-based rate renewal proceeding while a DPT is conducted and considered.65

In reply, APPA/TAPS state that there is no reason to raise the market share indicative screen threshold above 20 percent simply because investor-owned utilities have trouble passing the market share indicative screen.66 NRECA and TDU Systems note that the factors that EEI believes make it difficult to pass the indicative screens—a large amount of reserves and little available transfer capability—are precisely the factors to consider when evaluating whether a market is competitive.67

Rather than raising the threshold level, TDU Systems propose to lower the threshold to 15 percent for the market share indicative screen, claiming that 20 percent was never justified by the Commission or shown to be the right balance.68 Citing Commission and judicial precedent, TDU Systems also note that the grant of market-based rate authority cannot be made without the discipline of market forces.69

These commenters cite a recent decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit70 to buttress their positions, arguing that even market shares lower than 20 percent can lead to market manipulation.

In reply to these arguments, Duke states that certain commenters’ reliance on this is mistaken because that decision addressed market manipulation, not market power.71 Duke asserts that virtually any supplier, regardless of its market share, has some ability to manipulate market outcomes by engaging in anomalous bidding practices.

Commission Determination

The Commission will retain the 20 percent market share threshold for the indicative market share screen. EEI and others argue that the Commission should use a 35 percent threshold as a presumption of market power because the DOJ merger guidelines state that only firms with 35 percent or more market share have market power. As the Commission stated in the July 8 Order, however, in a market comprised of five equal-sized firms with 20 percent market shares, the HHI is 2,000, which is above the DOJ/FTC HHI threshold of 1,800 for a highly concentrated market, and in markets for commodities with low demand price-responsiveness like electricity, market power is more likely to be present at lower market shares than in markets with high demand elasticity.72 Therefore, we will retain a conservative 20 percent threshold for this indicative screen.

When arguing that a 20 percent threshold for the market share screen is too low, E.ON. U.S. and PNM/Tucson ignore that the indicative screens are based on uncommitted capacity, not total capacity. When calculating uncommitted capacity for the market share screen, a seller deducts from its total capacity the capacity dedicated to long-term sales contracts, operating reserves,73 planned outages, and native load74 as measured by the appropriate native load proxy. As a result, a substantial amount of seller capacity may not be counted in measures of market share. Therefore, it is inappropriate to compare market shares based on uncommitted capacity to the market shares in the cases that E.ON. U.S. and PNM/Tucson cite.

We further note that other commenters have argued that the 20 percent threshold is too high. We disagree. The 20 percent threshold is meant to strike a balance between having a conservative but realistic screen and imposing undue regulatory burdens. The Commission’s experience in the context of market-based rate proceedings demonstrates this point. In the three years since the April 14 Order, the Commission has revoked the market-based rate authority of two sellers, thirteen sellers relinquished their market-based rate authority, and six companies satisfied the Commission’s concerns for the grant of market-based rate authority at the DPT phase. In addition, intervenors have the opportunity to present other evidence such as historical data in order to rebut the presumption that sellers lack market power.75 Moreover, no commenter advocating a 15 percent threshold for the market share has shown why it is superior to the current 20 percent threshold. Therefore, we find that the 20 percent market share threshold strikes the right balance in seeking to avoid both “false negatives” and “false positives” and we will not reduce the wholesale market share screen to 15 percent, as suggested by TDU Systems.

The Commission does not accept Duke's assertion that the market share indicative screen is incompatible with regional planning requirements. The April 14 Order allows operating reserves necessary for reliability, as determined by state or regional reliability councils,76 to be deducted from total capacity attributed to the seller.

We also reject the argument that the 20 percent threshold is too low because of native load obligations of investor-owned utilities outside of RTOs. First, the calculation of 20 percent is the same regardless of whether a seller is located in an RTO or not. Second, as discussed herein, we allow for a native load deduction in the wholesale market share screen and are increasing the deduction to address concerns raised by investor-owned utilities and others. Given the increased native load deduction, our market share screen adequately incorporates investor-owned utilities’ native load obligations while necessarily maintaining the conservative nature of the screens.

b.Pivotal Supplier Application Period

Comments

Some commenters recommend that the pivotal supplier indicative screen should be applied monthly, rather than just in a seller’s peak month. They reason that sellers, though not pivotal in the highest demand period, might be pivotal at different times of the year or in off-peak periods, such as in the spring or fall when power plants are on planned outages.77