Overview for collection

overviewEquitable Distribution of Effective Teachers7 28 11.docx

Equitable Distribution of Effective Teachers: State and Local Response to Federal Initiatives

Overview for collection

OMB: 1875-0260

Equitable Distribution of Effective Teachers: State and Local Responses to Federal Initiatives: Task 2 OMB Package

Equitable

Distribution of Effective Teachers:

State and Local Responses

to Federal Initiatives

The Policy and Program Studies Service (PPSS) of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests clearance for the data collection for the study, Equitable Distribution of Effective Teachers: State and Local Responses to Federal Initiatives (EDET). The purpose of this study is to examine the actions that states and districts are taking to ensure teacher quality for disadvantaged students (i.e., students in high-poverty or high-minority schools), and the role of federal programs and policies in these actions. To this end, the evaluation will involve telephone interviews with one to three respondents in 52 state education agencies (SEAs) and 75 leading-edge school districts nominated by the states as being on the leading edge of contending with and addressing the issue of equitable distribution within their jurisdictions. Clearance is requested for the study’s design, telephone interviews, and analytic approach. This submission also includes the clearance request for the data collection instruments.

This document contains three major sections with multiple subsections:

Equitable Distribution of Effective Teachers: State and Local Responses to Federal Initiatives

Overview

Introduction

Study Objectives and Evaluation Questions

Conceptual Model

Study Components and Sampling Design

Data Collection Procedures

Analytic Approach

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Justification (Part A)

Description of Statistical Methods (Part B)

This study, Equitable Distribution of Effective Teachers: State and Local Responses to Federal Initiatives (EDET), will provide a broad and in-depth picture of the actions that states and districts are taking to ensure the quality and effectiveness of teachers for disadvantaged students (i.e., students in high-poverty or high-minority schools)—a central purpose of several federal programs. This study will examine how states and school districts are responding to these initiatives and what aspects of state and local context facilitate or challenge the implementation of federal programs.

Federal programs have increasingly focused on the equitable distribution of teacher quality. The most recent reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 2002 placed substantial policy emphasis on the key role of teachers by requiring that by the end of 2005–06, all core subjects be taught by highly qualified teachers (HQTs). In addition, ESEA required that states provide assurances and develop plans to “ensure that poor and minority children are not taught at higher rates than other children by inexperienced, unqualified, or out of field teachers” (Section 1111(b)(8)(C)). In 2009, American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) requirements reinforced the focus on equitable distribution of teachers by requiring states applying for education stimulus funds to provide updated assurances and to publicize their most recent “equity plans.” ARRA also established competitive grants to help states build their pool of effective teachers and address inequities in the distribution of teachers, through, for example, the Race to the Top (RttT) program, for which one priority area is effective teachers and leaders.

In addition to their focus on the equitable distribution of teacher quality, federal programs have also been promoting shifts in how teacher quality is measured, away from teacher qualifications and toward measures of instructional practice and effectiveness at raising student achievement. Legislation passed since the 2002 reauthorization of ESEA does not mention HQT status, which has been a difficult indicator to interpret because of variation across states in the specific benchmarks used (e.g., cut points for passing on licensure tests) and the high percentage of HQTs in most schools (Birman et al., 2009). In addition, recent research has documented the limited extent to which commonly measured qualifications, such as possession of a master’s degree, are related to student outcomes (Wayne & Youngs, 2003; Kane, Rockoff, & Staiger, 2008). In response to these findings and to several current federal and foundation initiatives, states and districts have begun to use data on student achievement (e.g., “value-added” measures), as well as demonstration of instructional practice, to judge teacher effectiveness. Federal programs such as the Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF) and RttT have provided incentives for states and districts to move in this direction, including funds to support some of the technical aspects of the development of measures of teacher effectiveness.

The first component of the study will consist of a set of state-level interviews in all 52 state education agencies (SEAs) to obtain a complete picture of state responses to the multiple federal initiatives aimed at fostering equitable distribution of effective teachers. State respondents will provide data on the actions states are taking, for example, to examine differences in teacher quality across schools, to improve measurement of teacher quality, and to ensure that children in all districts and schools have effective teachers. The state interviews will generate national data on the ways in which states’ development of equity plans required under Title I and under ARRA’s State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF) contribute to state actions, and on the ways in which state participation in other federal programs contribute to state actions.

The second component of the study will include interviews with local officials—identified initially through respondents from the state interviews—in 75 “leading edge” districts in the area of equitable distribution—districts that their states say are contending with and addressing—with whatever degree of success—this issue. Local school district procedures and conditions—for example, initial recruitment, hiring, and placement practices; working conditions in high-poverty schools; rules about teacher transfers that often are built in to collective bargaining agreements; and targeting of professional learning opportunities on low-performing schools—account for some of the differences in teacher quality across schools (Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2007; Goldhaber, 2008; Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 2004; Levin, Mulhern, & Schunck, 2005). The district interviews will examine actions taken to improve the quality of teachers, especially in disadvantaged schools—i.e., those that have high proportions of minority students or children from low-income families. The study will examine the actions of districts to recruit teachers and place them in disadvantaged schools, provide incentives for teachers to work in these schools, and target professional learning opportunities, among other actions, and will examine the role of federal programs in requiring or supporting these actions.

Study Objectives and Evaluation Questions

The objectives of the study are to describe three types of state and local activity that are encouraged by current federal policies and are related to teacher quality for disadvantaged students (Objectives 1, 2, and 3). The study’s objectives also include understanding how federal policies, and state and local contextual factors, shape these types of activity (Objective 4).

To examine how states and districts analyze the distribution of teacher quality, plan actions to address inequities, and monitor progress. Both ESEA and ARRA require that states have plans to address inequities in the distribution of teacher quality. The development of such plans implies a process in which states and districts examine the distribution of teacher quality, plan actions to address disparities across districts and school quality of teachers, and monitor progress toward reducing these inequities. The effectiveness of the federal planning requirements depends on the depth and care with which states and districts approach this complex process. Implicitly, states should determine what measures to use in determining teacher quality, what criteria they will use to determine whether a disparity is “inequitable,” and what actions they think would be effective in addressing the disparities. Some states and local education agencies (LEAs) are likely to be more systematic than others in conducting empirical analyses of the distribution of teacher quality to inform the development of equity plans, for example. ED monitoring reports indicate that many states may not review these data regularly to update their plans. To better understand the strengths and weaknesses of the planning process, the study will document these variations.

To examine how states and districts are changing their measures of teacher quality, and to understand their experiences in doing so. For reporting and planning purposes, teacher quality has been largely defined through the HQT provisions of ESEA (Title IX, Part A, Section 9101(23)). A shift is underway towards alternatives that include expert and/or peer evaluation, teacher portfolios, and outcome-driven effectiveness measures, such as value-added or growth models using student test scores. The development and use of such measures pose technical and implementation challenges. For example, methodological issues concerning the stability and validity of value-added estimates remain unresolved (see, for example, Koedel & Betts, 2009). Similarly systematic approaches to using teacher observation in the evaluation of teachers are just beginning to be implemented. This study will document the extent to which states and districts are moving toward such measures, the challenges that they face in doing so, and how some have overcome these challenges.

To examine state and local actions to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students (i.e., students in high-poverty and high-minority schools). States and districts can take many different types of actions to ensure that all students have access to high-quality teachers and to address differences across districts and schools. A broad array of strategies—aimed at recruiting the best candidates, streamlining the hiring process, or keeping effective teachers in low-achieving schools—have been implemented. Recent programs support removing ineffective teachers as an approach to ensuring teacher quality in the lowest performing schools (e.g., the Title I School Improvement Grants program). These actions differ in their purposes, costs, and political implications. For example, “career fairs” to recruit more candidates to disadvantaged schools may be more popular and less costly than monetary incentives to retain teachers in these schools. And incentive programs or increasing professional development opportunities, in turn, may be more feasible than removing ineffective teachers. The study will describe the range of actions that states and districts report taking to improve the distribution of teacher quality between schools with high concentrations of low-income and minority students, and the rationales behind these strategies and actions.

To describe the perceived contributions of federal programs to state and local strategies and actions aimed at improving the quality of teachers for disadvantaged students, and how state and local contexts mediate these contributions. Federal programs comprise a mix of requirements, assurances, and incentives (i.e., financial support). These various policy levers interact with state and local contexts. For example, federal programs (e.g., TIF) aim to promote the uses of incentives to attract good teachers to high-poverty schools. However, the size of the incentives necessary to attract teachers may depend on the demographic characteristics of a neighborhood (i.e., how much of a monetary incentive is necessary to attract teachers to an unsafe or isolated neighborhood); the size of an incentive also may be shaped by local budgets or collective bargaining agreements. The contribution and ultimate impact of federal programs is a result of a complex interplay of federal policies and state and local contexts. This study will capture the range of factors reported to shape state and local actions.

The evaluation questions for the study elaborate on these objectives, as shown in Exhibit 1.1 The first three evaluation questions correspond to Objectives 1, 2, and 3. The remaining two evaluation questions address different aspects of Objective 4.

Exhibit 1. Evaluation Questions

EQ 1. Analysis of data on equitable distribution. What actions do states and LEAs report to analyze the distribution of teacher quality, and to plan and monitor progress?

1.3 Are states and LEAs developing plans and monitoring plan implementation to ensure the equitable distribution of teachers? For example, how frequently are plans updated, how are states monitoring implementation of LEA plans? |

EQ 2. Development of new measures. What actions do states and LEAs report to develop new measures of teacher quality, and do they use these measures to examine the distribution of teacher quality? 2.1 What new measures of teacher quality and breakdowns are states and LEAs examining? 2.2 Are states and LEAs considering or beginning to use teacher effectiveness measures that reflect student achievement and/or demonstration of instructional practice. If so, in these states and LEAs: 2.2.1 What are the measures of teacher effectiveness, and what are their key features? 2.2.2 What motivated them to consider the measures? 2.2.3 Are they using the measures to examine the distribution of teacher quality? 2.2.4 What have they learned about using the measures? For example, what challenges have they encountered? |

EQ 3. Strategies for making the distribution of effective teachers more equitable. What strategies and actions do states and LEAs report to make the distribution of teachers more equitable across schools? 3.1 What strategies and actions do states and LEAs report to ensure high-quality teachers for schools with high proportions of low-income or minority students? Have actions been taken in the areas of recruitment and retention, school conditions, or preparation and professional development? 3.2 On what basis do states and LEAs focus their actions? For example, do they target high-poverty schools or high-minority schools, and do they target teachers with particular qualifications? 3.3 To what extent do states and LEAs report using measures of teacher effectiveness in developing their strategies and actions to ensure high-quality teachers for schools with high proportions of low-income or minority students? 3.4 What evidence do states and LEAs have about the effect of their strategies and actions? 3.5 What challenges have states and LEAs encountered in actions to ensure high-quality teachers in schools with high proportions of low-income or minority students, and how have states and LEAs addressed those challenges? |

EQ 4. Role of federal programs. What have been the perceived roles of federal programs (e.g., through formula programs like Title I and competitive grant programs, such as Race to the Top or Teacher Incentive Fund) in state and LEA actions related to the equitable distribution of teachers? 4.1 What have been the perceived roles of federal equity plan requirements in state and LEA analysis, planning, and progress monitoring? 4.2 What have been the perceived roles of federal programs in state and LEA efforts to develop better measures of teacher quality and of the equitable distribution of teachers? 4.3 What have been the perceived roles of federal programs in state and LEA efforts to ensure high-quality teachers for schools with high proportions of low-income or minority students? |

EQ 5. Distribution of teacher quality and context for state and LEA strategies. According to states and LEAs, what is the status of the distribution of teacher quality in states and LEAs, and what aspects of context shape the responses of states and LEAs to differences in teacher quality across schools? 5.1 What do states and LEAs identify as the primary differences in teacher quality across schools? Do states and districts collect any of the following data and use it for purposes of determining whether teachers are equitably distributed: teacher experience, HQT status, out-of-field status teacher scores on licensure tests, time to passage on licensure tests, and other indicators? If so, by school poverty, minority composition and/or high/low performance, what are the differences in each of these variables? 5.1.1 Does the distribution of teacher quality look different when using teacher effectiveness measures if states and districts collect such data? 5.2 What shapes the strategies and responses of states and LEAs to differences in teacher quality across schools? For example, do differences in fiscal capacity, restrictions in uses of student outcome measures, agreements with teacher organizations, or other factors affect state and LEA strategies and responses? |

Conceptual Framework

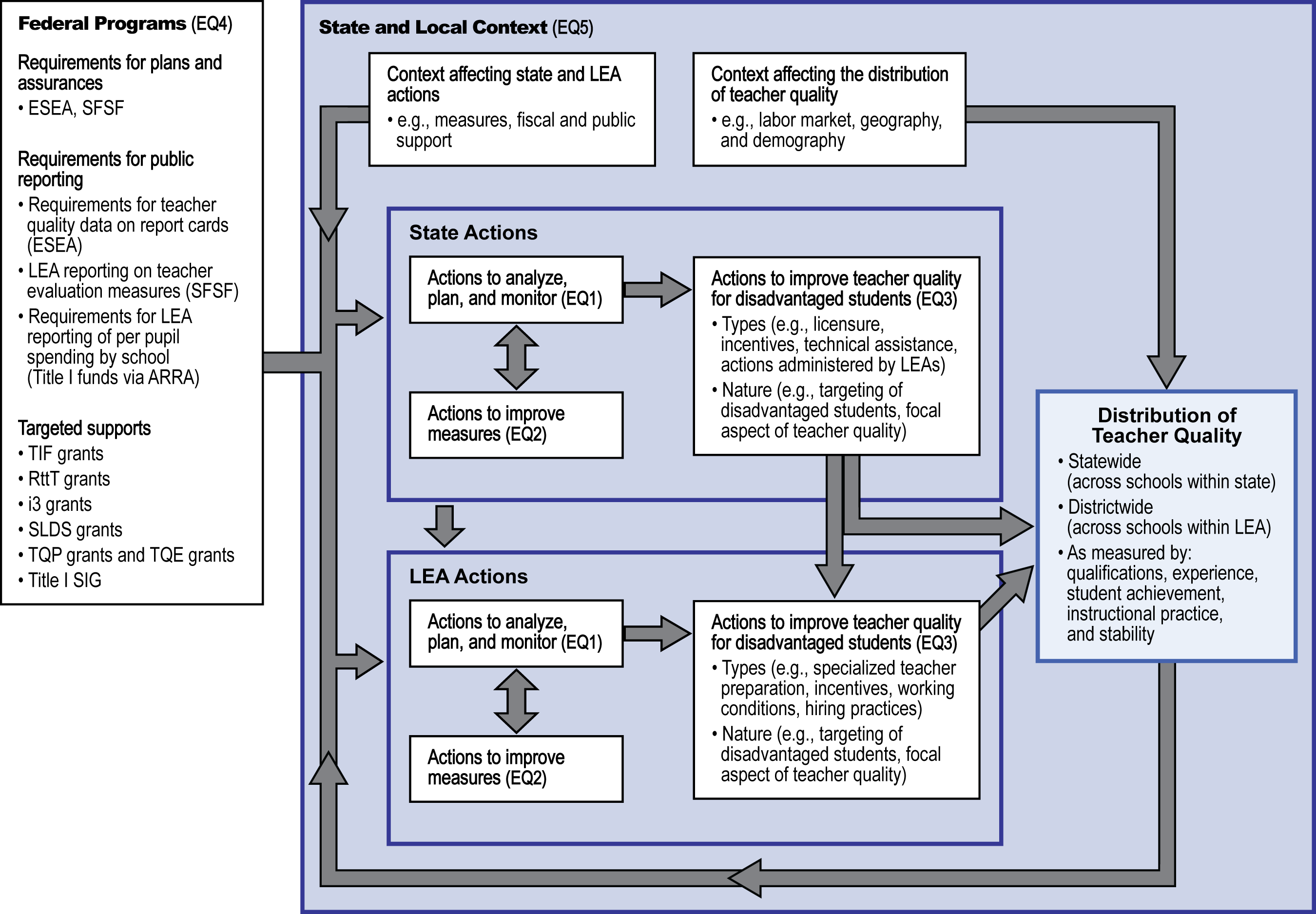

The instruments developed for the study are based on the evaluation questions and on the study’s conceptual framework, depicted in Exhibit 2, which appears on the next page. The conceptual framework posits the relationships among federal policies, state and local activities, and state and local context, including the distribution of teacher quality. Several aspects of the graphic are noteworthy.

Multiple federal programs are relevant. The left side of the conceptual framework indicates that many federal programs may affect how states and districts measure teacher quality and ensure teacher quality for disadvantaged students (i.e., students in high-poverty or high-minority schools), although only a few programs will likely operate in any single state or district. These programs rely on different levers to encourage, require, or support state or local actions.

Some programs require states and LEAs to develop plans and provide assurances about addressing inequities (i.e., ESEA and ARRA, including the SFSF requirement to publicize the most recent state equity plans), which may spur new efforts to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students.

Some programs require public reporting, which may affect public support. Key requirements include comparisons of the percentage of classes taught by HQTs in high- and low-poverty schools (ESEA), descriptive information on teacher evaluation systems (SFSF), and information on per-pupil spending, reported school-by-school, to include teacher salaries (ARRA funds for Title I).

Some programs provide targeted support for specific purposes, in the form of competitive grants (e.g., TIF, RttT), which may spur new efforts to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students, or add to state and local capacity to do so effectively. Participation in these programs will differ by state and district. In addition to TIF and RttT, relevant competitive grant programs include the Investing in Innovation Fund (i3), State Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS), Teacher Quality Partnership Grants (TQP), Teacher Quality Enhancement Grants (TQE), and Title I School Improvement Grants (SIG).

The study will examine states’ and districts’ perceptions of the role that these programs have played in the actions they have undertaken. In some cases, the federal programs may have reinforced existing actions or decisions; in other cases the programs may have spurred new actions or be contributing to state or local capacity.

Actions to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students may take different forms. States and districts can undertake a broad range of actions, including, for example, monetary incentives, induction programs, recruitment activities, and even teacher preparation reforms. Actions are relevant to this study provided that they are targeted on disadvantaged students, or are intended to address aspects of teacher quality that are least prevalent in schools with large numbers of disadvantaged students. Recent technical assistance publications list various possible actions to

Exhibit 2. Conceptual Framework

improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students, and include references to relevant research (see Imazeki & Goe, 2009).

State actions to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students are often administered by districts. States and LEAs differ in their relationship to teacher quality. Because LEAs hire teachers and determine rules for teacher transfers (often governed by collective bargaining agreements), LEA actions are likely to have a more direct effect on the distribution of teachers across schools. While some state actions also directly affect schools (e.g., statewide incentive programs), state actions often operate through districts, which are required to administer particular state programs or policies.

The three types of state and local actions—measurement, planning, and actions to improve the distribution of teacher quality—are related. The federal equity plan requirements and federal supports for new measures of teacher quality imply a theory of action whereby:

State and local actions to improve measures of teacher quality (EQ2) can inform analysis and planning (EQ1). For example, Tennessee’s initial analyses for its equity plan focused on teacher qualifications. A later analysis that used Tennessee’s system for measuring the effectiveness of teachers at raising student achievement spurred a range of further planning and analysis activities in the state (Carr & Oxnam, 2009).

Analysis and planning (EQ1) help shape the actions taken to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students (EQ3). For example, states may determine that teacher quality disparities between low and high-poverty schools are occurring within districts, rather than between districts, and so states may focus their actions on developing within-district programs and requirements (Behrstock & Clifford, 2010; Imazeki & Goe, 2009).

Thus, in the implied theory of action, the effectiveness of state and local actions taken to improve the quality of teachers for disadvantaged students likely depends on valid measures of teacher quality and careful analysis of where the problems lie.

State and local context play a role. A key feature of the study’s conceptual framework is its attention to contextual factors that mediate federal initiatives (EQ5). Some of these contextual factors are the geographic or demographic factors that affect teacher labor markets. Urban centers with high percentages of students in poverty, for example, have particular difficulty attracting good candidates because of teachers’ preferences to teach affluent students. Limitations in state or district data systems may limit a state’s ability to use newly developed measures. Declines in fiscal support may constrain state and district actions. State and local contexts also may facilitate responses to federal initiatives. For example, some states and localities may have a history of attention to improving teaching in high-poverty schools, or may have positive union relationships that facilitate the adoption of incentive programs. The study will examine factors that both challenge and facilitate the implementation of federal initiatives.

The distribution of teacher quality in each state and LEA affects actions. The equitable distribution of teacher quality is the goal of many federal programs and is depicted in the conceptual framework as an outcome. In addition to being an outcome, the distribution of teacher quality is an important aspect of state and local contexts. As states and LEAs increasingly focus on teacher effectiveness and monitor disparities across schools, this information factors into state and local planning and, thus, continually shapes state and local actions and responses to federal requirements, according to the conceptual framework. The extent to which states and LEAs collect useful information about the distribution of teachers, and how this information shapes their planning and actions will be an important focus of the study.

Study Components and Sampling Design

The main components of this study are presented below in Exhibit 3 along with the proposed sample. A detailed discussion of the sampling design is provided in the Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission, Part B section of this package.

Exhibit 3. Main Study Components and Proposed Sample

Study Components |

Sample |

Collection Time |

State telephone interviews |

52 SEAs (all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico) |

February 2012 |

Local Education Agency (LEA) telephone interviews |

75 leading-edge LEAs |

March 2012 |

The data collection for this study includes telephone interviews with states and LEAs, as presented above in Exhibit 3. A detailed discussion of data collection procedures is provided in the Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission, Part B section of this package. Copies of the notification letters, informed consent forms, and interview protocols for the state and LEA interviews are included in Appendixes B, C, D, and E, respectively.

The state and LEA interviews will generate data on the three types of activity—analysis, planning, and monitoring (EQ1), improving measures (EQ2), and actions to improve teacher quality for disadvantaged students (i.e., students in high-poverty or high-minority schools) (EQ3)—as well as data on the role of federal programs (EQ4) and state and local contexts (EQ5).

Interviewers will review extant sources prior to each interview to streamline interview questioning. For some questions, state Web sites may provide authoritative, up-to-date information, which the research team will confirm through interviews. For most questions, extant sources will provide somewhat dated, incomplete information, which interviews will seek to update and clarify. The data collection procedures and extant sources are described in detail in the section on data collection procedures provided in the Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission, Part B section of this package.

Interview analysis will be conducted separately for the state and LEA levels. The first phase of interview analysis will consist of coding of text data, an iterative process that includes reading, reviewing, and filtering data to locate important descriptions and identify prevalent themes relating to each evaluation question. Once meaningful categories of policies and practices are identified, in the second stage analysts will produce counts (e.g., counts of the number of states that mandate induction programs for high-poverty schools). Finally, the research team will identify exemplar cases or narratives that illustrate key policies and practices and that provide detailed contextual information. The reports produced on the basis of these analyses will include disclaimers to clarify that the results of these analyses are not generalizable beyond the sample from which the data were collected.

The analytic tools that the contractor has developed for analyses of interview data on state and LEA policy implementation have five critical features: (a) a format that is amenable to both quantified and text data; (b) a flexible interface, in which new variables can be inserted or in which data can be updated easily; (c) fields to indicate when data were updated; (d) flags to indicate when data are uncertain and need to be verified; and (e) mechanisms to facilitate basic counts, tabulations, coding, and charts. In the past AIR has successfully and efficiently customized Excel spreadsheets to meet data analysis needs.

1 For a crosswalk showing how these evaulation questions align to questions from the data collection instruments, see Appendix A.

![]()

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Andrew Abrams |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-02-01 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy